|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Benelli B76 Pistol By Ed Buffaloe

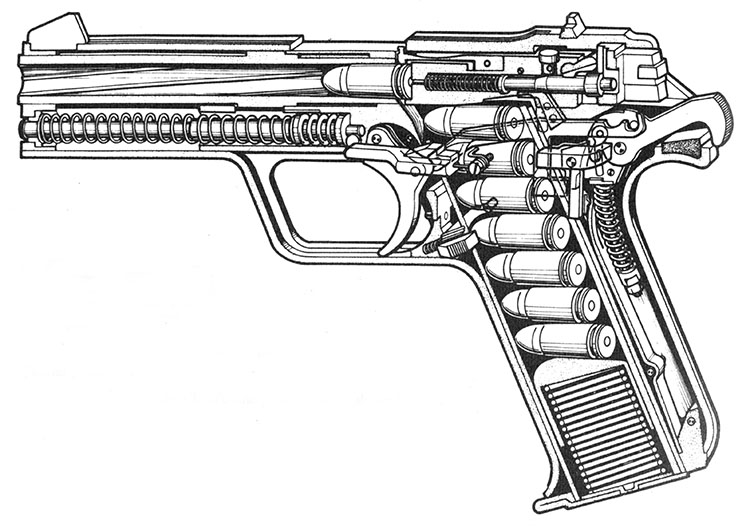

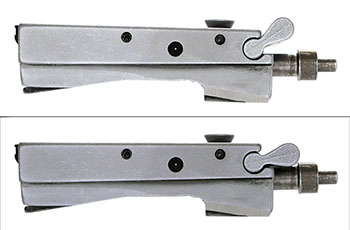

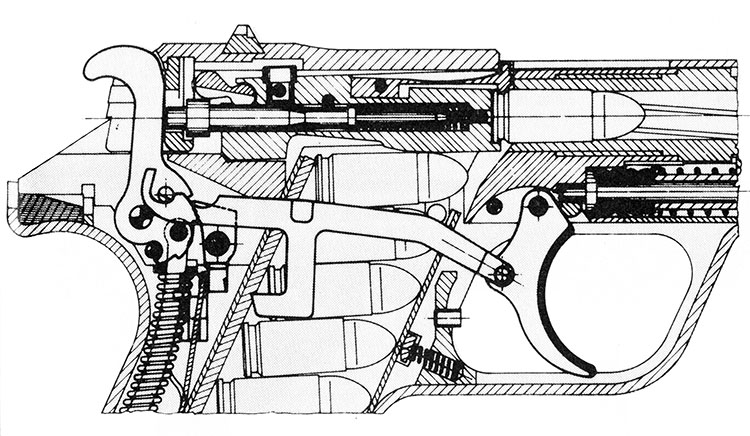

The gun consists of a frame with a fixed barrel, a slide, and a separate breech block, or bolt, which contains the top-mounted extractor, the firing pin, and the lock mechanism. The lock mechanism is a little “flapper” or toggle on the rear and the patent refers to it as the “locking link.” The slide has a closure piece which fits into the rear and serves as the means of disassembly.

Benelli also manufactured similar guns in smaller calibers including the B77 in 7.65mm Browning (.32 ACP), the B82 in 9mm Ultra, and an MP3S target version in .32 Smith & Wesson Long, but these guns did not require the inertial lock mechanism of the B76. However, Benelli also manufactured a version of the MP3S target gun in 9mm Parabellum, and the B80 in 7.65mm Parabellum (.30 Luger); both require the inertial lock. The Benelli B76 in Print This is just a quick survey of the publications available to me that mention the B76. If a reader knows of an article I have missed, I would appreciate being informed.* I presume that the B76 designation indicates production beginning in 1976. If so, the B76 got off to a slow start in the U.S., probably due to limited distribution when the gun was still new. I find the first mention of the B76 in the 1978 Gun Digest which said it became available in late 1977, but the gun is not listed for sale anywhere in 1978.

The first real information on the B76 is a brief but thorough review in the April 1979 issue of American Rifleman, and it provided the essentials of how the gun operates, its features, some nice photographs and diagrams, and the results of accuracy testing—two inch groups at 25 yards. The article states: “There were no functional problems with full metal jacketed bullets, but cartridges loaded with soft point or hollow point bullets did not feed reliably...”. The B76 was listed as available from Sile Distributors for $290.50, but it does not appear in either Gun Digest or Guns Illustrated for 1979. In the 1980 Gun Digest, J. B. Wood praises the B76 very highly in his column “Handguns Today: Autoloaders,” saying “...the double action trigger system is the smoothest of any auto pistol I have ever fired.” He also commented that he fired some very respectable groups on his first day at the range with the gun and said “The balance of this pistol must be felt to be believed. The quality is superb...”. The gun is listed in both the 1980 Gun Digest and Guns Illustrated, and the price continued to be $290.50. For comparison, the price for an eight-shot Smith & Wesson Model 39 was $210.50 in 1980. The first bare mention of the B76 in American Handgunner is found in the January/February 1980 issue, in a list of available 9mm pistols, but I could find no further information or commentary on the pistol in 1980. In the January/February 1981 issue of American Handgunner, there is an article by Bert Myers in which he praises the quality of manufacture of the B76, particularly the hard chromed interior parts, but noted “The Benelli is quite fussy about the ammunition it digests. Only the loads that conform to the length of military hardball seem to go through every time.” The price listed in the article was $349.95, the same as that found in the 1981 Gun Digest, and also in Guns Illustrated, and the B76 continued to be listed at this price for the rest of its short lifetime.

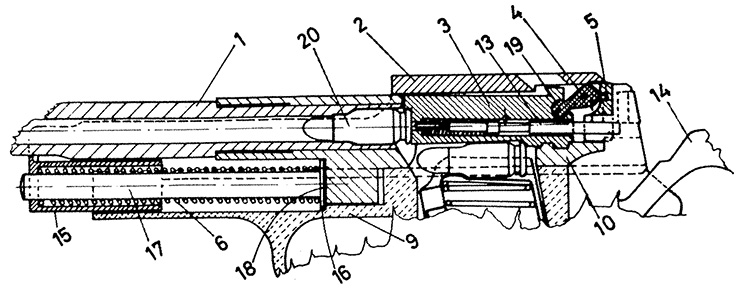

The May/June 1983 issue of American Handgunner has a brief note that the second generation Benelli B76 was seen at the SHOT show that year. In the July/August 1983 issue of American Handgunner, Al Pickles provides a review of the B76 Tournament model which has an extended Magna-Ported barrel and an adjustable rear sight. He says the double-action trigger has a long throw that will be a reach for people with small hands and also that “...Federal’s 123-grain metal case (#9AP) 9mm cartridge delivered groups of less than two inches at 25 yards and four-inch groups at 50 yards.” The most serious attempt at an explication of the B76 mechanism was by Donald M. Simmons, Jr. in his 1984 Gun Digest article “Benelli’s B76: Lots more gun than most people know”. According to Simmons, Giovanni Benelli was granted an Italian patent for his breech lock mechanism in February of 1972. He filed his patent in the United States a year later, on 23 February 1973, and was granted U.S. patent number 3,893,369, on 8 July 1975. I will further reference Simmons’ article below. The September/October 1985 issue of American Handgunner notes that. at the Nuremburg trade show, “Benelli was showing their Model MP36 [sic], a target version of the B76 in 9mm and .32 Wadcutter”. They also mentioned that there were no plans for importing these guns into the U.S., and this may explain their extreme scarcity here today. By 1986 the Benelli B76 is no longer listed in Guns Digest or Guns Illustrated, so the effective lifetime of the gun on the U.S. market was less than a decade. The Patent and the Locking Mechanism Based on the patent drawings, the gun appears to have been designed around the 7.65mm Parabellum (.30 Luger) cartridge. The bolt shown and described in the patent has twin locking lugs , or ribs, on its base that fit into matching grooves in the receiver, and a link on its rear which can rotate up and down in an arc of about 15°.

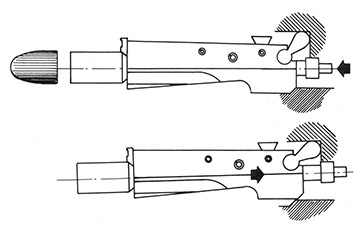

The abstract of the patent states: “A locking link provided between the bolt and the bolt carrier is caused, upon firing, to rotate in such a direction that said link holds bolt urged against the receiver breech, with said ribs engaged in the mating grooves. Once the inertial force of said bolt carrier has failed, the residual pressure of exhaust gasses applies a force to said bolt which causes the bolt to rotate with respect to said receiver breech so as to disengage said ribs from the associated grooves in said receiver breech.” In the production pistol, the twin locking lugs become a single large lug at the rear of the bolt which fits into a recess in the frame. The locking mechanism can be challenging to describe in words, but is quite simple in application.

When the bolt is pressed up against the barrel, its rear end slips down into a recess in the receiver. The inertial force of the weight of the slide, combined with the force of the recoil spring, presses the slide against the locking link on the back of the bolt. The toggle or locking link, on the back of the bolt, is forced up at a 45° angle by the slide and its attached closure piece, while the firing pin protrudes through an oval hole in the back of the closure piece. The inertia of the closure piece/slide causes the angled link to press down on the bolt and locks it to the slide. The breech is fully locked at the time of ignition. When the cartridge is ignited, the bolt remains locked for the few microseconds necessary for the bullet to leave the barrel; during this very brief period of time, the slide recoils about 2mm while the bolt remains locked to the frame. As the slide recoils, it allows the link to fall, unlocking the bolt which, in turn, allows the bolt to be cammed upward by the tiny slanted surface at its bottom rear corner. A cut in the top of the slide engages with the circular guide in the top of the bolt, carrying the bolt backward with the slide and ejecting the spent cartridge. Features and Build The Benelli B76 has a 4.25 inch fixed barrel and a single stack magazine that holds eight cartridges. The manual safety lever on the left side of the gun moves straight up and down; it locks the hammer, the transfer bar, and the slide simultaneously, and is also used to lock the slide open for disassembly. The hammer has a half-cock position; the safety will lock the hammer in cock, half-cock, or down position. The transfer bar is on the right side. A tail on the end of the transfer bar serves as a disconnector to force the transfer bar down and out of alignment with the sear and hammer when the slide is out of battery. The trigger operates in both double and single action mode. The transfer bar acts directly on the hammer in double action mode and on the sear in single action mode. The thumb operated magazine release is pressed forward to drop the magazine. The extractor, like many that are top mounted, serves as a loaded chamber indicator which can be seen or felt. The B76 is one of the few production guns with a factory installed adjustable trigger stop.

The B76 frame is made from two stamped halves of .08 inch sheet steel that are welded together and then machined smooth. According to Simmons, this is reminiscent of the Ruger .22 auto pistol and the German Jäger pistol. I find the Jäger comparison a bit of a stretch—while it was made from two pieces of sheet steel, the Jäger was not stamped or formed, but die cut and punched. I am reminded more of the Gustloff Werke pistol, the Steyr GB, or the Heckler & Koch Model 4 slide. The B76 has a subframe to which are attached all moving parts, plus the barrel. The subframe, the slide, and the bolt are machined from bar stock. The barrel is screwed into the subframe which, in turn, is held in the frame by five roll pins. The barrel, the subframe, the closure piece, and all internal moving parts are hard chromed. Simmons states that he tried every kind of corrosive ammunition he could find, and left it in high humidity for days, to see if he could damage the hard chromed barrel, but it remained pristine. My own experience is that the B76 barrel is incredibly easy to clean—nothing sticks to it. Simmons also notes: The forward part of the chamber has a series of grooves running with the axis of the barrel. These grooves, during firing, allow a small amount of gas to slip by the throat of the case of the cartridge. The pressure inside and outside of the case mouth [is] equalized and this tends to float the cartridge, allowing easy extraction. The fired case does not show any grooves because they are so small. This system helps prevent any welding of the case to the chamber wall during firing which can lead to case rupture and other ills.

Simmons states further that the extractor on the B76 is only necessary for removing a loaded cartridge from the chamber. He states that, once the slide is unlocked, blowback action from residual gases forces the cartridge out, even when the extractor is removed. The B76 magazine is made of thin steel with a molded reinforcing rib at the back and has open slots on either side for viewing cartridges. The plastic follower has a notch to activate the slide lock when the magazine is empty and also features round dimples on either side to aid in pulling the follower down for loading cartridges. The B76 has a matte blued finish, with the hammer, trigger, barrel, and subframe being hard chromed. The grip plates are checkered walnut. Early guns are marked on the left side of the slide in all capital sans-serif characters: BENELLI ARMI S.P.A. – URBINO – ITALY And on the right side: SILE DISTRIBUTORS N.Y. – N.Y. Later guns are marked on the left side: BENELLI ARMI S.P.A. – URBINO – ITALY Late guns may have the right side of the slide unmarked. Field Stripping the Benelli B76

Range Report The accuracy of the B76 is no joke. At the shooting range, I had set some clays up on the berm. I had planned to walk down to about 20 feet from the berm to shoot but, just as I loaded a magazine, someone else drove up, meaning that I could not redefine the firing line without their consent. Therefore, I fired from 25 yards, with no rest, and was gratified to see the first clay pulverized with a single shot. The B76 points quite naturally, though I have to break my wrist a little further down than usual, to accommodate the acute grip angle. In this regard, the B76 is a lot like the Chiappa Rhino revolver.

Despite J. B. Wood stating that “...the double action trigger system is the smoothest of any auto pistol I have ever fired”, I found the double action trigger pull on the B76 to be unacceptably heavy, at 16 to 17 pounds, as well as too long. The six pound single action trigger pull is just right for me since I am accustomed to double action revolvers that usually come in at 10 to 12 pounds. The single action is quite smooth and positive, with no creep. Recoil is manageable, and the B76 is well balanced, just as Wood claims. There are definitely issues with the B76 feeding of short 9mm ammunition. 115 grain Federal full metal jacket cartridges were easily digested; these cartridges measure 1.155 inches. I also had no issues with Sierra 115 grain jacketed hollow point ammunition which measures 1.110 inches. However, when I tried some Remington 115 grain jacketed hollow point ammunition there were major problems; this ammunition, which measures 1.080 inches long, would not even load properly in the magazine, let alone feed or eject. This is largely due to the acute angle of the magazine. A cartridge got wedged at right angles, so tightly that I had to disassemble the magazine to get it out. I would strongly recommend not shooting any ammunition that measures less than 1.110 inches. * Write to edbuffaloe@unblinkingeye.com. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright 2022 by Ed Buffaloe. All rights reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||