|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Chiappa Rhino Revolver by Ed Buffaloe

Patent and Design

Ghisoni’s patent for the Rhino lists several objects of the invention, including:

There

By now, everyone knows that the special feature of the Rhino revolver is that it fires from the bottom chamber of the cylinder rather than the top. The lower barrel axis serves to direct recoil forces to the rear instead of up, considerably reducing barrel flip and speeding target reacquisition for subsequent shots. The trigger on the Rhino is set forward, beneath the center of the cylinder, rather than at the rear of the cylinder as on Smith & Wesson or modern Colt revolvers. This allows the grip to also be set forward by about three-quarters of an inch. The Rhino is a more compact revolver design with a very different feel and balance from a Smith & Wesson or a Colt. The grip angle is a little more acute than that on traditional revolvers, so the wrist must be turned down somewhat more when aligning the sights.

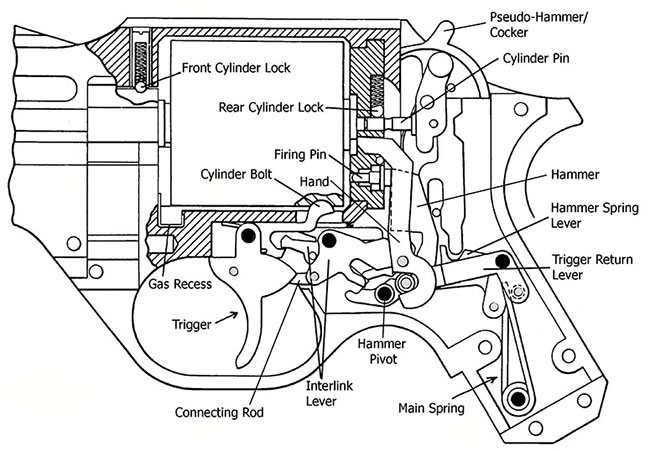

The Rhino is three-quarters of an inch shorter in length than the six-shot Smith & Wesson Model 13 revolver which is also chambered for .357 magnum. Nominally, both guns have three-inch barrels, but actually the Smith & Wesson barrel is slightly shorter and the Rhino barrel is slightly longer. The cylinder on the Rhino is 1/16-inch shorter than the Smith’s. The all steel Smith & Wesson weighs 34 ounces, whereas the aluminum-alloy-frame Rhino weighs 28 ounces. Terminology It appears that for the U.S. Patent filing the Italian patent was translated into English using a translation engine, without further editing. In the patent the cylinder is called the “drum,” the hand is called the “rotation foot,” the cylinder bolt is called the “anchor,” and the cylinder release is called the “control element,” so it is difficult to make head or tails of the patent’s text without frequent reference to the drawings. To provide additional confusion, the grip end of the revolver is referred to as the “fore-end.” The parts list for the Rhino is somewhat better, though a number of pins are referred to as “rollers,” but a useful and necessary terminology does emerge from the parts list, which is reflected in the diagram below. Of course, technically speaking, the cylinder on the Rhino could be called the hexagonal prism but let’s not go there. Internals

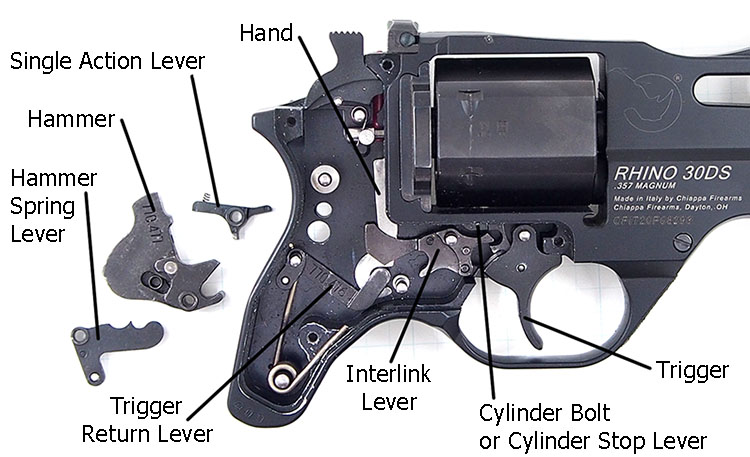

The internal hammer on the Rhino is set low in the frame so it can engage the bottom chamber of the cylinder. The trigger on the Rhino does not directly engage the hammer or the cylinder bolt. Instead, there is an additional component in the Rhino that sits between the trigger and the hammer; in the patent it is called the “inner distributor,” but in the parts list it is called the “interlink lever.” When the trigger is pulled, the interlink lever serves several purposes: (1) it releases the cylinder bolt, (2) it operates the hand to turn the cylinder, and (3) it engages the double-action sear on the hammer to fire the gun. A transfer bar or connecting rod connects the trigger to the interlink lever. A separate component, known in the patent as the “counter-hammer” and in the parts list as the “single action lever,” is hinged at the same point as the interlink lever and serves to lock the hammer back for single action firing (essentially serving as the single action sear).

A single coil mainspring with two arms, at the rear of the gun, tensions the hammer via the hammer spring lever and also tensions the trigger via the trigger return lever, hand, interlink lever, and connecting rod. The trigger return lever tensions the hand which turns the cylinder. The cylinder turns in a clockwise direction and the hand is on the left side of the gun. Since the sideplate is on the right side, this means the hand is among the first components to be fitted into the gun, with the trigger, interlink lever, and trigger return levers going in next. A pin in the left rear side of the interlink lever engages the hand.

In its rest position, the rear arm of the interlink lever engages a pin on the left side of the hammer, holding the hammer back so it cannot strike the firing pin. As long as the trigger is held to the rear, the arm of the interlink lever is rotated down and cannot engage this pin and, hence, allows the gun to be fired.

When the trigger is pulled the connecting rod pushes back on the interlink lever and rotates it. A nose on the front of the interlink lever lowers the cylinder bolt, freeing the cylinder, while a pin on the interlink lever pushes the hand upward to rotate the cylinder. Simultaneously, a toe at the bottom rear of the interlink lever engages the double action sear to rotate the hammer backward. When the hand moves up to turn the cylinder, it pushes up a cylindrical red indicator on the left side of the frame, just behind the rear sight. This indicator serves as a warning that the gun is cocked. The cocker or pseudo-hammer has a spring that holds it in the forward position at all times, so it does not remain at the rear when the internal hammer is cocked which is why the cocking indicator is necessary. If the gun were double-action-only, the cocking indicator would not be necessary. I would personally prefer that the gun be double-action-only, but I understand that some shooters like the single action mode for target shooting and hunting. At least with the current design the cocker in no way interferes with shooting the gun double action. My only complaint would be that the cocker is difficult to operate but, since I rarely utilize it, it is a moot point. A recess in the frame at the base of the cylinder, where it meets the barrel, is designed to vent gases from the ignition of the cartridge. As the patent says, the recess is “suitable for conveying them laterally to avoid dirtying the hand.”

When the cylinder release is depressed, and the cylinder swung out from the frame, the cylinder release remains in the down position. In the down position, a foot on the cylinder release lever, inside the frame, is interposed just above the hand, essentially locking the action while the cylinder is out of the frame. Features and Handling Characteristics The reduction in muzzle flip with this design is significant and should not be understated. Hot loads with heavy bullets, that are uncomfortable to shoot in a J-frame Smith & Wesson, are perfectly comfortable to shoot in the Rhino. The rubber grip on the Rhino model 30DS is superb at absorbing recoil, and I can’t help but think that the small grip frame surrounded by rubber on all sides contributes to effective recoil absorption. Recoil is mostly into the palm of the hand and the shooter has a much greater sense of control over the muzzle when shooting at speed. When the Rhino first came out I read that the trigger pull was not optimal (about 15 pounds double action), so I waited ten years before buying one, assuming they would have the bugs worked out by then. The gun I bought seems to average about a twelve pound trigger pull. I normally prefer something in the 10 to 11 pound range, but the very short double action trigger stroke and wide trigger make twelve pounds seem acceptable to me. The manual I got with my gun lists a “970.291 Trigger Conversion Kit” and a “970.453 Trigger Conversion Kit Gen II.” The first one is said to be available with five different springs, ranging from 4.6 Kg (10.4 pounds) to 2.5 Kg (5.5 pounds), but I have been unable to locate one of these kits anywhere. The second kit is said to be suitable for competition only. The front sight has a red fiber optic insert, and the rear sight has two green inserts, providing superb visibility in strong light. The 30DS comes with three star clips and the cylinder is cut for them. I’ve never found a convenient way to carry loaded star clips, so I usually just carry a speed loader or a cartridge pouch. My preferred Safariland speedloaders do not work well with the Rhino, but other brands do. Working on the Rhino I do not recommend that you remove the sideplate on your gun, unless you are very familiar with revolver mechanisms, and even then you might want to think twice. Striking the base of the grip to loosen the sideplate can easily result in components coming loose and falling out. I spent an hour figuring out how to put my gun back together the first time I did this. It helps to have a photograph of the interior of the gun printed out before you start. If you insist on removing the sideplate, I recommend a single very light blow to lift it slightly, then prying very carefully so as not to damage anything. I find it nearly impossible to remove the sideplate without removing some of the black anodyzed finish somewhere around it. Be patient. Even a single light blow will raise the hammer spring lever part way off its axis, so be sure to press it back into place once you get the sideplate off. There are several small rollers that can easily be lost, so go slow and be careful. The aluminum alloy of the Rhino frame seems much softer than that used in Smith & Wesson revolvers. I don’t have a scientific way to prove this, but it seems to me that it is easily damaged. Unlike Smith & Wesson alloy frames, the Rhino has a steel backplate in the cylinder window. The black anodyzed finish on my Rhino is delicate but it is easy to touch up using Birchwood Casey Aluminum Black. I found the serrations on the edge of the cylinder release lever to be rather sharp, so I took a file to them and then retouched the steel with some Brownell’s 44/40. A Word About Aesthetics Opinions vary widely. One friend’s reaction was: “MANNNNN... That is one ugly revolver!!” Others seem to think the design is futuristic, innovative, and cool. In fact, a long barrel version of the Rhino made an appearance in the science fiction series The Expanse, largely because it looks so futuristic. My concern in writing this article has been functionality. The Rhino allows the use of the most powerful and lethal .357 cartridges without the usual trade-offs of excessive recoil, or excessive weight, in the gun. That being said, I would welcome a sleeker, perhaps more aesthetically pleasing version, in highly polished blued steel.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright 2021 by Ed Buffaloe. All rights reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||