|

.44 Special Revolvers

by Ed Buffaloe

I am well aware how many articles on the .44 Special cartridge are currently available, as well as articles about the legendary Smith & Wesson “triple-lock” revolver. But I have enjoyed my .44

Special revolvers so much over the years, and especially in 2020, the year of the COVID-19 pandemic, that I want to share my enthusiasm for the cartridge and the guns by offering brief reviews and comments on some of the guns

in my collection, taking the opportunity to compare and contrast them, and providing an overview of .44 Special revolvers on the new and used market today. Ideally, I would be as objective as possible, but I also feel there is

a place for subjective impressions, and I hope my readers will forgive me if mine may differ from their own. I will present the guns in the order in which they were manufactured.

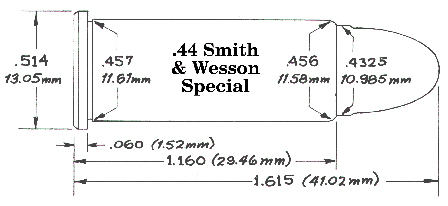

The .44 Smith & Wesson Special cartridge first appeared in 1907, made for the Smith & Wesson

New Century “triple-lock” revolver (see below). According to Dean Grennell, “a few prominent target shooters of the day” had called for a large caliber target cartridge, and Grennell maintains

that Smith & Wesson always intended the cartridge primarily for target use, even loading it down somewhat to improve accuracy. He says: “No real effort was ever made to push it for military

service, nor was much done to interest law enforcement in the caliber.”

The original load for the .44 Special was 26 grains of black powder, to propel a 246 grain bullet, producing a muzzle velocity of 755 feet per second, but this soon gave way to various

smokeless powder loadings with a standardized muzzle velocity of 770 feet per second. With a 246 grain bullet, this standard load produces a muzzle energy of about 325 foot-pounds. But, with smokeless powder,

there is plenty of room in the cartridge case for additional propellant so today many companies load a multitude of bullet styles and weights to velocities anywhere from 750 feet per second up to

as high as 1200 feet per second, producing muzzle energies from about 230 to over 600 foot pounds, making for a very versatile selection of contemporary cartridges.

An obsession with the .44 Magnum, beginning about 1956, led to a decline in interest in the .44 Special but more and more shooters today are realizing that the .44 Special occupies the sweet

spot between minimum stopping power and too much recoil. For the average shooter, a .44 Magnum is often more gun than they need or want. Even a low velocity .44 Special cartridge is

more powerful than a standard velocity .38 Special, and a high velocity .44 Special can rival or exceed the stopping power of a .357 Magnum, with nearly identical recoil.

|

Testing Some Modern .44 Special Cartridges in a 3-inch Barrel

|

|

Brand

|

Bullet Weight (grains)

|

Bullet Type

|

MuzzleVel. (fps)

|

Energy (ft-lbs)

|

|

Black Hills

|

210

|

LFP

|

742

|

257

|

|

Buffalo Bore

|

200

|

WC

|

978

|

425

|

|

Corbon

|

165

|

JHP

|

1168

|

502

|

|

Fiocci

|

210

|

LFP

|

718

|

240

|

|

Handload - 5.1 grains Unique

|

200

|

WC

|

733

|

239

|

|

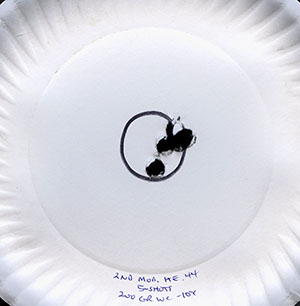

Handload - 5.1 grains Unique

|

208

|

WC

|

727

|

245

|

|

Handload - 6.1 grains Unique

|

250

|

WC

|

783

|

342

|

|

Hornaday Critical Defense

|

165

|

JHP

|

886

|

289

|

|

Hornaday FTX

|

165

|

JHP

|

917

|

309

|

|

Hornaday XTP

|

180

|

JHP

|

799

|

256

|

|

Speer Gold Dot

|

200

|

JHP

|

747

|

249

|

|

Steinel (Speer Gold Dot bullet)

|

200

|

JHP

|

1036

|

477

|

|

Underwood (solid copper)

|

125

|

XD

|

1203

|

402

|

|

Underwood

|

190

|

SWCHP

|

1067

|

480

|

|

Underwood

|

200

|

WC

|

905

|

364

|

|

Underwood

|

255

|

SWC

|

957

|

519

|

|

Winchester Silvertip

|

155

|

JHP

|

742

|

190

|

|

Winchester Silvertip

|

200

|

JHP

|

725

|

234

|

|

New Century 1st Model Hand Ejector .44 Special

This is the first gun ever made for this cartridge. The Smith & Wesson New Century has been praised by any number of experts as possibly the finest revolver ever manufactured. This may be

hyperbole but the gun is certainly well and beautifully made. It was the last caliber to appear in a series of hand ejector models which were the first Smith & Wesson guns with swing-out cylinders,

the earliest of which was the .32 Hand Ejector of 1896, followed by the .38 Hand Ejector of 1899.

The .44 Special New Century became the flagship large caliber handgun of the Smith & Wesson company.

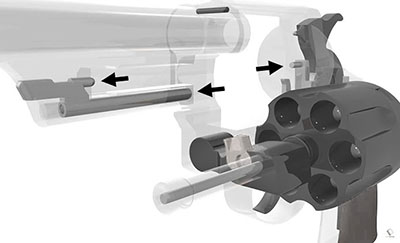

In 1902, Joseph H. Wesson filed a patent for a locking mechanism for the yoke, or crane, of a revolver cylinder. Up to that time, Smith & Wesson revolvers had locked the cylinder pin at front and rear but

this new design added a third lock at the front of the crane. U.S. Patent 702607 was granted on 17 June 1902, though the New Century revolver did not actually appear until 1908. The third lock gave the gun the

nickname it retains today: the “triple-lock.” Only 15,375 New Centuries were made in .44 Special, after which the design was

simplified, and the third lock abandoned, never to be made again. The next version of the gun (the Second Model .44 Hand Ejector) was reduced in price by nearly fifteen percent.

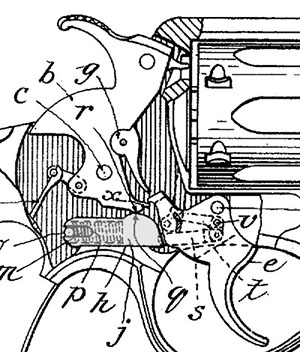

Another innovation,

which is often overlooked when people write about the New Century, but which remains a standard feature of Smith & Wesson revolvers to this day, is the rebound slide. Earlier

Smith & Wesson revolvers already had a rebounding hammer, which means that after the gun is fired and the trigger is released the hammer rebounds slightly so that the firing pin cannot reach the cartridge. This is a safety

mechanism so if the thumb should slip while cocking the revolver the gun will not be able to fire.

However, the older mechanism, which used a rebound lever tensioned by a flat spring which also tensioned the trigger, caused a less than perfect trigger pull so, in

1905, Joseph H. Wesson filed a patent for a new mechanism that used a coil spring to tension the trigger and also to effect the rebound of the hammer. The coil spring runs down the center of a steel block that sits

beneath the hammer and behind the trigger. The spring serves to return the trigger after a double-action trigger pull and also tensions the cylinder hand, while a bump on top of the block holds the hammer back

from the cartridge so long as the trigger is in its forward position. Joseph Wesson referred to it as a “slidable wedge-block” but we know it today as the rebound slide. He was granted U.S. patent

811807 on 6 February 1906.

The New Century has several features not found on modern-day Smith & Wesson Revolvers. The first thing I noticed when I disassembled my gun is that there is a spring and plunger in the base of

the crane. Supica & Nahas state that this is “...to assist holding the cylinder open.” The second thing I noticed, after removing the sideplate, is that the outer surfaces of the cylinder bolt,

rebound slide, double-action sear, hand, and cylinder stop are polished to a mirror finish. The rebound slide has the patent date on it, and also has a horizontal lug on its back side that fits into

a slot milled in the frame. The cylinder bolt has a set screw to hold the spring and plunger that tension it. The hammer and trigger are case hardened. The gun is a “five screw” design, with

four screws to hold the side plate and a fifth screw, with spring and plunger, in front of the trigger guard to tension the cylinder stop.

The New Century was made from 1908 until 1915. My gun was made in 1910. After 110 years, it still functions flawlessly. When I took it apart the action did not appear to have been cleaned or

lubricated for many years

so I removed all the components and cleaned them thoroughly, put a dab of modern lubricant in a few strategic locations, and reassembled the gun. I made no attempt to do a “trigger

job” because I wanted to keep the gun in its original configuration. The double action trigger pull measures 12.5 pounds, and the single action pull is 5 pounds. Both are very smooth, with a crisp and predictable

single action release. This gun was designed for single-action target shooting, though the double action is remarkably smooth. I might try to reduce the double action trigger pull by a pound or two, but I would hate

to ruin the nearly-perfect single action let-off. My gun has the 7½ inch target barrel with a drift-adjustable “Bisley” rear sight. It groups well and points naturally.

The grips are a little small for my hand, but I wanted to keep them original so I added a grip adapter.

Second Model Smith & Wesson .44 Hand Ejector

The Second Model Hand Ejector is essentially the same gun as the First Model minus the third locking lug. Eliminating the locking lug allowed the elimination of the large ejector shroud under

the barrel. Inside I found the same highly polished lockwork components, but the rebound slide no longer has the patent date or the lug on the backside. The cylinder bolt no longer has a set screw.

Otherwise my Second Model, which was made in 1926, remains virtually identical to the First Model. The question I really wanted to answer was, does it shoot as

well as the First Model? The answer is, indeed it does! It appears that the third locking lug makes no difference to the accuracy of the revolver.

My Second Model has cheaper grips with no medallions and also has a lanyard on the base of the grip. Again, I retained the original grip plates but added a grip adapter

to make the gun easier to hold. This gun had a 13 pound double action trigger pull and a 5 pound single action pull. I couldn’t resist taking a few thousandths of an inch

off the strain screw, reducing the double action pull to 11.5 pounds and the single action pull to 4½ pounds. That seemed not too drastic a change for the old gun. With a 6½ inch barrel, it is slightly less unwieldy

than its older cousin, but no less accurate.

Colt New Service .44

According to James Serven, the Colt New Service appeared in 1897 and was discontinued in 1943. Built on a large, heavy frame with a swing-out cylinder, this was the first Colt double-action

revolver with a cylinder that revolves clockwise, and with a side-plate on the left side. The New Service has a very large grip frame, clearly made for men with big hands. The gun weighs 46.75

ounces, just an ounce and a quarter short of three pounds.

Though Serven does not say as much, I think it safe to say the New Service frame was designed for the .45 Colt cartridge; the gun is also found chambered in .38 Special

, .357 Magnum, .38-40, .38-44, .44 Special, .44-40, .45 Auto; as well as the British .450, .455, and .476 Eley. It holds six cartridges, and has a fixed front sight and a

groove on the topstrap that serves as a rear sight. Target versions have adjustable sights front and rear.

The gun shown here was made in 1925. When I got it the double action trigger pull was 15 pounds. I did not want to make changes to it, but I could barely pull the trigger, so I bent the mainspring to give a double action pull of 13 pounds. Despite being made to accommodate double

action shooting, Colt pistols were always intended to be shot single action by manually cocking the hammer.

The grip of the Colt did not fit my hand well at all, so I added a grip adapter. The old gun groups

well, but shoots low at 10 yards. Again, I did not want to alter it, so I did not attempt to file the front sight to correct this issue. The single-action trigger pull is 4.5 pounds. It has a very different

feel from my other revolvers, but I was able to shoot a reasonably tight group with it. The Smith & Wesson New Century has a slightly heavier single action trigger pull than the Colt, but the Smith &

Wesson trigger feels smoother than the Colt and I can more readily predict when it will break.

Charter Arms Bulldog

My first .44 Special was a Charter Arms Bulldog. The Charter Arms .44 Bulldog first appeared in

1973 and for ten years was the only production .44 Special on the market. I can’t say it was solely responsible for the resurgence of interest in the .44 Special cartridge but I can say that new models

in .44 Special began to proliferate after 1983. Charter Arms has always made budget guns but they are well made and an excellent value for the money. The Charter Bulldog uses a one-piece frame

with no side plate, allowing it to be somewhat lighter than other revolvers of a similar size.

I have owned several Bulldogs over the years, but my favorite carry piece is a stainless steel version made in Stratford, Connecticut in about 1981. The gun weighs 23.5 ounces, so it is easy to

carry, though recoil is appreciable with heavy 240 grain bullets. I have standardized on 200 grain bullets and I put Pachmayr rubber grips on the gun to help reduce felt recoil as much as possible.

Even with rubber grips the Bulldog is not comfortable to shoot for long periods

but it serves me well for concealed carry and is more than accurate enough for defensive purposes.

One disadvantage of the Charter Arms design is that it is not as easy to work on as Smith & Wesson or Ruger revolvers, so there is less you can do to improve the

trigger pull. Neither the double nor the single action trigger pull is as smooth or crisp as a Smith & Wesson. You can always polish the engaging surfaces of the

trigger and hammer but the trigger is more difficult to reinstall than on other revolvers. I have tried reduced power hammer springs on several Bulldogs and in every

case the spring worked fine for a time and then I began to experience light strikes on hard primers. I think the best one can hope for is to smooth the action a bit by some

judicious polishing but I have given up on changing out or modifying the spring. The hammer can be shimmed to reduce drag--shims are available from triggershims.com, and a video is available on how to install them.

Rossi Model 720

The Rossi 720 was available from 1993-1999, with a spurless-hammer double-action-only version (720C) appearing in 1995. The gun is a virtual Smith & Wesson clone, with the 720’s

frame being the same size as the S&W L frame, though it is not as heavy and uses a coil mainspring like the Smith & Wesson J frame. The Rossi frame is only a little thicker than a J frame but is

considerably deeper to accommodate the larger cylinder. The Rossi weighs in at just over 31 ounces, almost a half-pound heavier than the Charter Bulldog but a quarter-pound lighter than a

Smith & Wesson Model 696 L frame. Because the added weight absorbs recoil better, it is more comfortable that the Charter Bulldog for extended shooting sessions. The rubber grip is well

designed and comfortable in the hand. Though I generally prefer a grip without finger grooves, the Rossi grip fits my hands well.

I was stunned by the accuracy of the Rossi 720. This is a seriously good-shooting revolver. I was also surprised at how well finished the interior parts are. The action can

be polished and lighter springs fitted in an identical manner to a Smith & Wesson. The only difficulty comes when trying to find reduced power springs—no one

makes them, so all you can do is try to reduce the existing springs. Before I did that I bought some original replacement springs—they can be found periodically on either Ebay or Gunbroker and also at M&M Gunsmithing. My Rossi 720 has a trigger pull of about 14 pounds. I

was able to get this down to 12.5 pounds by trimming the hammer spring slightly but I began to get light strikes on hard primers so I went back to the original spring. I spent

a lot of time polishing the interior of the frame and all the internal parts to smooth the trigger pull but I gave up on reducing the pull weight. If it had a lighter trigger pull, this would be the perfect

.44 Special revolver. However, the accuracy of the Rossi somewhat makes up for its less-than-perfect trigger.

.44 Special Revolvers Continued on Next Page

|

Make/Model

|

# Shots

|

Weight

|

Length

|

Barrel Length

|

Double Action

|

Single Action

|

|

S&W New Century Target Model

|

6

|

40.1 oz

|

12.63”

|

7.5”

|

12.5 lbs

|

5 lbs

|

|

S&W 2nd Model Hand Ejector

|

6

|

38.25 oz

|

11.63”

|

6.44”

|

13 / 11 lbs

|

5 / 4.5 lbs

|

|

Colt New Service .44 Special

|

6

|

46.75 oz

|

10.81”

|

5.5”

|

15 / 13 lbs

|

5 / 4.8 lbs

|

|

Charter Arms Bulldog

|

5

|

23.45 oz

|

7.86”

|

3”

|

12 lbs

|

4 lbs

|

|

Rossi Model 720

|

5

|

31.25 oz

|

8”

|

3”

|

14 lbs

|

4 lbs

|

|

S&W Model 696

|

5

|

36 oz

|

8”

|

3”

|

12.5 / 10 lbs

|

5 / 2 lbs

|

|

S&W Model 296

|

5

|

19.8 oz

|

7.63”

|

2.48”

|

13 / 10.5 lbs

|

NA

|

|

Taurus 445

|

5

|

21.5 oz

|

7”

|

2.12”

|

15 / 12 lbs

|

4.5 / 4 lbs

|

|

S&W Model 21-4

|

6

|

37.2 oz

|

9.21”

|

4”

|

13 / 11 lbs

|

5 / 3 lbs

|

|

Ruger GP-100 .44 Special

|

5

|

35.8

|

8.39”

|

3.07”

|

13 / 11 lbs

|

4.5 / 3 lbs

|

|

|