|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Notes on Practical Shooting by Ed Buffaloe

Originally I thought to title this short article ‘Notes on Instinctive Shooting,’ but in reacquainting myself with Ed McGivern’s classic book, Fast and Fancy Revolver Shooting, I was reminded that he used the term ‘practical shooting,’ which he distinguished from ‘target shooting,’ and Julian Hatcher used the same terminology in his 1935 book Textbook of Pistols and Revolvers. The terms ‘speed shooting’ and ‘point-shooting,’ are also often used. Aiming is usually required, though not necessarily with the sights. The shooter must learn to aim very quickly, and the primary tool in aiming is the mind.

Fairbairn and Sykes, in their book Shooting to Live, were of the opinion that ‘what has been learned from target shooting is best unlearned if proficiency is desired in the use of the pistol under actual fighting conditions.’ Ed McGivern expressed quite the opposite opinion, though he wasn’t talking about combat: ‘Regardless of the many arguments that have been advanced on the subject, it is the writer’s opinion that proper training in slow fire stationary target shooting, which develops steady holding, sure hitting, and good grouping, cannot possibly be and is not...a detriment to later development in rapid fire or to superspeed group shooting...’ Fairbairn and Sykes were concerned with up-close-and-personal combat situations where someone is actively trying to kill you and a split second one way or another is the difference between life and death. So they emphasized survival rather than extreme accuracy. McGivern, on the other hand, proved that extreme accuracy was possible even one-handed at extreme speeds. Fairbairn and Sykes were training police and intelligence agents in as short a time as possible, whereas McGivern was an exhibition shooter and emphasized the need for long and continuous practice in order to achieve the accuracy he was famous for. It took him years to master his skill set, and he would often practice for several days or a week before giving a shooting exhibition. Fairbairn and Sykes enumerate three essential points in regard to practical shooting:

My notes and comments here will touch only on the first two points. My Goal

My inspiration came when I watched a video by Jerry Miculek on how to shoot a pistol, which I highly recommend (see below). Jerry is a competition shooter who can shoot really fast, with great accuracy—and his insights are quite valuable. He emphasizes how important it is to relax, stand naturally, square to the target, get a high grip on the gun, bring the gun up to your dominant eye, eliminate unnecessary movement, and strive for repeatability. He is one of the best shooters in the world, and he is a good guy to learn from. Thus inspired, I started going to the gun range every week, sometimes twice a week, because there is simply no substitute for regular practice. I would usually take three guns, two revolvers and a semi-auto pistol. I was working on an article about .44 Special revolvers, so I always had one of those with me, but I also shot various .38, .357, and .32 revolvers. I was able to compare the guns against each other and consider what worked best for me. I would typically shoot about fifty rounds in each gun, then go home and think about how I had shot with each gun and how I could improve either the gun itself or my technique in shooting it. Consciousness and Instinct You can’t think about what you are doing too much when you are actually doing it. The time for conscious thinking and analysis is before you start and after you are finished. Consciousness is good for planning for the future and remembering and analyzing the past, but it is much too slow for most practical purposes. If you had to stop and analyze the distance, the force vectors, and the acceleration of the rabbit when throwing a rock, you would never hit it because the rabbit would be gone before you finished your analysis. All that stuff takes place instinctively. How do you get good at throwing rocks? Lots of practice. Similarly, you are not fully conscious of everything you do when driving a car; most of it is instinctive and based on long practice. So you need to think about all the details before you start and instill good habits that will become instinctive over time. After you shoot you can think about why you succeeded or failed; you can spend time analyzing the little things you can do to make yourself faster and more accurate. Fit Not everyone is a collector, like myself, with a lot of guns to choose from, so let me first emphasize how important it is to find a gun that is a good ‘fit’ for you. Primarily this means a gun shaped to fit your hand properly and that allows your finger to reach the trigger in an optimum manner, but it also means a gun that is not too heavy for you to lift and carry regularly nor too light or poorly designed that it does not absorb recoil properly. Unfortunately, it is not always easy to tell if a gun is suitable until you have actually shot it. stocks on most revolvers can be easily swapped out or altered to fit your hands properly, and many of the new polymer frame auto pistols have interchangeable backstraps that can be swapped to fit the shooter’s hand. But the majority of auto pistols either fit your hand or they don’t and you have to choose one that suits you. I have learned to replace, modify, or enhance stocks, as necessary, on all my revolvers. My preference on small revolvers is for slightly oversized stocks that cover the backstrap. These may not be necessary on larger revolvers. However, many revolvers come with stocks made for small hands so larger stocks may be necessary anyway, depending on the size of your hands and length of your fingers. I prefer rubber stocks for recoil absorption, but without finger grooves. Finger grooves force you to hold the gun exactly the same way every time, which may be an advantage in some instances, but they can also prevent you from altering your hand position to improve your aim.

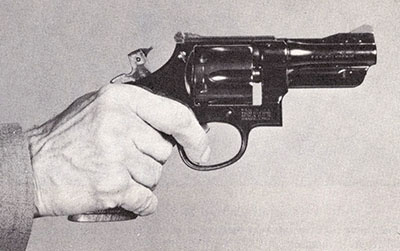

In some cases it may be preferable not to replace or alter the stocks so I generally add a grip adapter which fits on the front of the grip frame, just behind the trigger guard, and allows me to grasp the gun better. Smith & Wesson were offering grip adapters as early as the 1930’s and Pachmayr used to make grip adapters too but I don’t find them on their site anymore. The best known brand of grip adapter today is the Tyler T Grip, available from Tyler MFG. The T Grips are made of aluminum or bronze. There is also a small company called BK Grips that molds adapters out of some sort of polymer resin; I use these a lot because they work well, I can order from my computer, and shipping is fast. If a gun is not physically too large or too small, it is possible to adjust the way you hold it, the angle of your wrist, your off hand grip, and other factors to “fit” the gun so you can shoot it with instinctive accuracy. I do this by trial and error, though in cases of extreme difficulty you may have to consult an experienced shooter who can watch you to determine the cause of your problem. Gripping the Gun All shooting experts recommend getting a high grip on the gun. The barrel should be as low in relation to the hand as physically possible. This may feel a little awkward at first, but you quickly become accustomed to it.

For revolvers Jim Gregg says: ‘The top of the hand should be even with the hump of the backstrap.’ He also says that you need a strong grip to control recoil but if you grip the gun with all the strength you have the end of the barrel will shake and cause you to be inaccurate so you should always use a little less than full strength. If your hands are weak, you may have to work on strengthening them in order to control recoil. Trigger Control McGivern says: ‘Trigger control must first be learned by slow, careful shooting, while using the single-action method...of squeezing the trigger.’ Only then should one attempt to learn rapid double -action shooting. Some may consider this to be ‘one man’s opinion of moonlight’ but I will bow to the master’s opinion on this point. He also recommends ‘staging’ the double-action trigger (in contemporary terminology) by squeezing the trigger to the point that the cylinder rotates, then hesitating briefly to ascertain sight alignment, then squeezing further until the hammer falls. Obviously, McGivern did not do this when performing his high-speed shooting demonstrations, but he nonetheless recommended this method for developing trigger control and strength. McGivern also recommends standing in front of a mirror with an unloaded gun and slowly squeezing the trigger while watching the end of the barrel, the goal being to squeeze and release the trigger with no movement of the barrel, which is easily observed in the mirror. He emphasizes that the release of the trigger is equally important as the squeeze and should take the same amount of time. This develops both strength and control in the trigger finger. Jim Gregg suggests placing a quarter on the rib of a revolver barrel, just behind the front sight, and cycling the trigger repeatedly while keeping an eye on the coin: ‘...it should be steady from start to finish.’ He recommends working on accuracy first and speed will come when you gain confidence in your accuracy. McGivern states that he places his finger as low as possible on the trigger so he can exert maximum leverage. One of the modifications that J. Henry Fitzgerald used to make on his now-famous ‘Fitz Special’ revolvers was to straighten the trigger somewhat, making it easier to place the finger toward the bottom. Some modern auto pistols actually have straight rather than curved triggers. Sights and Aiming Fairbairn and Sykes taught shooting entirely without sights and even went so far as to remove sights from guns they trained with. They used human-sized targets with no markings and, if you could hit anywhere on the target, that was good enough. But I am looking for greater accuracy and my belief is that it is important to learn to shoot using the sights on the gun before you move on to rapid shooting with accuracy. McGivern says: ‘The “big idea” of not using sights in this work...has just about the same value as trying to get aerial targets to stop and wait for you while you shoot at them. That sights cannot be, and are not used, in this kind of shooting is a radically wrong impression...’ In discussing the importance of adjustable, target sights, Mcgivern says: ‘...guns with clear-cut, easily and accurately adjustable sights are necessary for even reasonable success...’ and ‘I...was very firm in the belief that a trained mind could direct correspondingly trained hands, eyes, and muscles to handle a revolver so as to positively and quite accurately use such sights on flying targets, and for various tests in superspeed group shooting...’ Jim Gregg has clearly read McGivern. Gregg writes:

The eye controls the hand, The hand controls the gun, and the gun controls the bullets. The steadier the eye, the steadier the bullets. First you must learn to shoot very deliberately using the sights. Once you have achieved accuracy and trigger control you can speed up. You progress to shooting multiple targets one after the other, quickly lining up the sights with the target. Then you move on to simply raising the gun and firing instinctively. McGivern says, ‘...the subconscious mind takes charge and makes corrections without any apparent conscious effort...’ With sufficient practice ‘...the subconscious mind can, will, and does make corrections instantly or within a very few hundredths of a second, while the gun and target are moving, and in plenty of time to score hits...’ The same is true if the gun is moving while shooting at stationary targets. For aimed fire, it is important to be able to see the front sight, particularly in unusual lighting situations. I established the habit of painting my front sight a bright green color. Some people prefer red or white: whatever you can see best. Birchwood Casey makes a Super Bright kit that gives you red, white, and green paints in easy-to-use pens. I add clear acrylic fingernail polish over the paint. Some revolvers come with sight inserts, which are usually red. I make my own inserts using one-hour epoxy mixed with a small amount of green paint. I prefer green paint or a green insert to a fiber-optic sight but, again, whatever you can see best.

To establish which eye is dominant is of critical importance for the shooter. It is not uncommon for a person to be right handed but left eye dominant or vice versa; this is called cross-dominance. If you are already able to shoot with accuracy, chances are you are right handed with a dominant right eye or possibly left handed with a dominant left eye. However, if you consistently hit to one side or the other of your target you may be cross-dominant. Some people have balanced vision, where neither eye is dominant, and they typically have a 50/50 chance of shooting accurately with either hand. Whatever your eye situation, it is important to understand it in order to learn to shoot well. Jim Gregg has defined both ‘master eye’ and ‘dominant eye’ and has analyzed fourteen different variations of eye/hand co÷rdination. I do not plan to go into all the possibilities in this article. If you are having serious problems with learning to shoot, you might want to buy Gregg’s book, or even consult an expert trainer. If you are cross-dominant, you must learn to compensate by turning the head slightly to use the dominant eye or turning the hand slightly to line the gun up with the dominant eye or some combination thereof. Assuming, of course, that you wish to keep both eyes open. You can also close your non-dominant eye but this limits your depth perception. With enough practice, compensation becomes unconscious—there is no real need to think about it. To determine your dominant eye, hold a pencil in your dominant hand, with your weak hand wrapped around it, as if you were grasping a gun, and line the pencil up with an object in the distance (at least 20 feet away). Then close one eye. If the pencil seems to move to one side, then you have just closed your dominant eye. If the pencil remains in the same orientation to the distant object, then you have closed your non-dominant eye. If the pencil seems to move to one side when you close one eye and to the other side when you close the other eye, then you have balanced vision. What I Learned I had spent years doing aimed fire at targets, so I was already quite familiar with guns, recoil, aiming, and the eye/hand relationship. I already knew that I was right-handed, and left eye dominant. What remained was simply to practice regularly and see if I could hit small targets in rapid succession at a range of three to six yards. I shoot at an outdoor gun club range where we have a high berm but are forbidden to shoot up in the air or into the ground. All shots must impact the berm. So it was out of the question for me to attempt aerial shooting, or skipping cans on the ground. But if I go early in the morning when no one else is there I can define a firing line anywhere I wish and shoot at multiple distances and at multiple targets while standing or moving. So I chose to shoot at skeet clays on the berm. The clays are bright red and about four inches across. I line eight or ten of them up approximately chest high, two to three feet from each other, so I have targets from my far left to my far right. Then I shoot as rapidly as possible at them. I started out aiming carefully at each target, aligning the sights. The brightly painted front sights on my guns aided me in doing this quickly. I progressed to hitting five out of five fairly quickly. When I missed, it was often only by an inch or two and I could see the clay jump even if it didn’t disintegrate. Then I progressed to shooting with the gun held at chest height in front of me (with both hands), but below my line of sight. I tried to simply point the gun as naturally as possible at the target and squeeze the trigger. I was surprised at how often I could hit the little clays, or at least get close. But sometimes too I would miss by several feet. I got hung up at this point for a time. Sometimes I would have a string of very accurate hits but they were often followed by a string of inaccuracies. I decided it was time to re-read Jim Gregg’s book, The Gregg Method of Fire Control,and see if I could figure out what I might be doing wrong.

Another expert, Andy Stanford, says: ‘...one key to accurate rapid fire is to keep the trigger busy. Instead of the traditional recipe of “aim then fire”—which often results in the shooter jerking the trigger in an attempt to take a “snapshot” of a good sight picture—correct the alignment of weapon and target while you are pressing/stroking the trigger.’ [My italics.] Eye-on-the-target is critical when shooting multiple targets at speed. If the gun is moving, the finger must already be squeezing the trigger before the sights line up with the target. If you are watching the gun, you will almost never squeeze the trigger at the right moment. With eyes on the target, the mind compensates for the movement of the gun. It begins to seem like magic but it is really subconscious eye/hand co÷rdination. Gregg says: ‘Firing a gun only substantiates a mental process, so the key to being a great shot lies in the mental process.’ That being said, Andy Stanford advises: ‘As the weapon discharges, watch the front sight lift from the target, even if you aren’t focused directly on the sight itself. The ability to describe where the sights were when the shot broke is a sign of an accomplished shooter. When you can do this consistently, you will be able to troubleshoot many marksmanship problems, identifying and then correcting your own errors.’ [My italics.] While a good shooter keeps his eye on the target, he is always peripherally aware of the front sight. I find I have good days and bad days. One day I can’t seem to miss and the next time I go I’m all over the place. If I’m not hitting the way I want, I go back to carefully aligning the sights until I get my confidence back. Then I revert to looking at the target over the sights. One Hand Shooting Until fifty years ago almost all handgun shooting was done one-handed, even target shooting. Then two-hand shooters began winning all the matches. But there is no getting around the fact that Ed McGivern did all his remarkable feats one-handed, and in a close-in self defense situation there may not be time to shoot with two hands and one-handed shooting becomes an instinctive reflex. So it is important to practice one-handed with each hand. At this point, I’m going to confess that one-hand shooting is beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say that Andy Stanford’s chapter in his book Surgical Speed Shooting is a must-read on the subject. I can’t possibly do a better job than he has done. Let me give one quick quote to get you started, and then I recommend you buy his book and read it carefully. He says: ‘One-handed shooting takes two primary forms: visually verified fire from eye level and unsighted shooting at contact distance from a weapon retention position. These variations address different tactical situations and require completely different techniques.’

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright 2021 by Ed Buffaloe. All rights reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||