|

We woke up sore from having climbed the mesa at Chaco

Canyon the day before. It was Sunday in Farmington, New Mexico. We ate a hearty breakfast and set out for Mesa Verde, via Shiprock, New Mexico. Even though it was out

of the way, I just had to drive through Shiprock because of all the Tony Hillerman mysteries I’ve read. We took mostly back roads to get there through the Navajo Reservation.

Many of the homes and ranch houses we saw had hogans (the traditional Navajo dwelling) near them and a few hogans existed all by themselves. I

had heard that overgrazing and soil erosion was a problem on Navajo lands, but this area looks pretty healthy. We didn’t see many sheep or goats though. On the way to Shiprock,

we passed by the new Navajo coal-burning power plant, which was belching out black smoke. There have been many complaints from environmentalists that this power plant is polluting the air

of the entire four-corners area, and this appears to be true. It is also true that the plant provides electricity to people who have been without it forever. I read an article in the Farmington paper

about a Hopi Indian who was suing the Navajo Nation for not hiring him to work at the plant. They were reserving the jobs for Navajos, but he maintained that as a native American they

should hire him anyway. The court found in favor of the Navajo, who have carte blanche on their own reservation. We woke up sore from having climbed the mesa at Chaco

Canyon the day before. It was Sunday in Farmington, New Mexico. We ate a hearty breakfast and set out for Mesa Verde, via Shiprock, New Mexico. Even though it was out

of the way, I just had to drive through Shiprock because of all the Tony Hillerman mysteries I’ve read. We took mostly back roads to get there through the Navajo Reservation.

Many of the homes and ranch houses we saw had hogans (the traditional Navajo dwelling) near them and a few hogans existed all by themselves. I

had heard that overgrazing and soil erosion was a problem on Navajo lands, but this area looks pretty healthy. We didn’t see many sheep or goats though. On the way to Shiprock,

we passed by the new Navajo coal-burning power plant, which was belching out black smoke. There have been many complaints from environmentalists that this power plant is polluting the air

of the entire four-corners area, and this appears to be true. It is also true that the plant provides electricity to people who have been without it forever. I read an article in the Farmington paper

about a Hopi Indian who was suing the Navajo Nation for not hiring him to work at the plant. They were reserving the jobs for Navajos, but he maintained that as a native American they

should hire him anyway. The court found in favor of the Navajo, who have carte blanche on their own reservation.

Shiprock is the administrative seat for the Navajo reservation (we gather from having read most of Tony Hillerman’s novels) and we did pass by the office of the Navajo Tribal Police. We

drove out the highway heading south from Shiprock so we could look at the butte the town is named for, and on the way we passed the Garden Apartments. I told Sybil it was a ridiculous

name, since they were sitting in the desert with no vegetation anywhere nearby, but Sybil replied that downstairs apartments are sometimes referred to as “garden” apartments. We quickly

turned around and headed north. Sometime I would like to spend more time in the Navajo country because I have been struck by the beauty and elegance of Navajo poetry and culture.

A lot of people tend to imagine New Mexico as primarily desert, and

much of it is, but New Mexico also contains some of the most beautiful scenery in the U.S. Nevertheless, A lot of people tend to imagine New Mexico as primarily desert, and

much of it is, but New Mexico also contains some of the most beautiful scenery in the U.S. Nevertheless,  the drive from Shiprock

to Mesa Verde tends to confirm the stereotype--it seems as though the desert ends and the mountains and forest begin as soon as you cross

the line into Colorado. I had forgotten how beautiful Mesa Verde is. (Why else would they call it the green mesa?) It is covered with trees, and

as we drove up the long road I thought to myself that those Indians really had it good on the mesa with all this beautiful forest and plenty of game. No wonder they loved it. I was amazed at how large the Park is. It’s

about 20 miles from the entrance to the major ruins and there are hundreds of other ruins scattered about the park tucked into crevice caves in the canyons. the drive from Shiprock

to Mesa Verde tends to confirm the stereotype--it seems as though the desert ends and the mountains and forest begin as soon as you cross

the line into Colorado. I had forgotten how beautiful Mesa Verde is. (Why else would they call it the green mesa?) It is covered with trees, and

as we drove up the long road I thought to myself that those Indians really had it good on the mesa with all this beautiful forest and plenty of game. No wonder they loved it. I was amazed at how large the Park is. It’s

about 20 miles from the entrance to the major ruins and there are hundreds of other ruins scattered about the park tucked into crevice caves in the canyons.

We set out immediately for a tour of the best-known site at Mesa

Verde, which is called Cliff Palace. I was all set to ignore a boring lecture, but the ranger was articulate and informed, and got my

attention right away. The first thing he told us was that when the Mesa Verde culture was at its height (so to speak) the entire mesa was denuded of vegetation. The top of the mesa had been cleared

for farming and the wood in We set out immediately for a tour of the best-known site at Mesa

Verde, which is called Cliff Palace. I was all set to ignore a boring lecture, but the ranger was articulate and informed, and got my

attention right away. The first thing he told us was that when the Mesa Verde culture was at its height (so to speak) the entire mesa was denuded of vegetation. The top of the mesa had been cleared

for farming and the wood in the canyons was cut to build houses and fires, so by the 1200’s the

Anasazi of Mesa Verde faced a severe shortage of wood. I should have known. The hunting probably wasn’t so good either. They raised corn, beans

, and squash, just as the peasants of Mexico still do. The ranger said they grew so much food they were able to send some down to Chaco Canyon

when times were bad there, though he didn’t say how they know this. The tour was primarily an historical one, rather than a “photo op” tour, but I

managed to make a few shots by lingering longer than anyone else. the canyons was cut to build houses and fires, so by the 1200’s the

Anasazi of Mesa Verde faced a severe shortage of wood. I should have known. The hunting probably wasn’t so good either. They raised corn, beans

, and squash, just as the peasants of Mexico still do. The ranger said they grew so much food they were able to send some down to Chaco Canyon

when times were bad there, though he didn’t say how they know this. The tour was primarily an historical one, rather than a “photo op” tour, but I

managed to make a few shots by lingering longer than anyone else.

The stone building technology at Mesa Verde came from

the Chaco culture. As I stated earlier, the ranger also said there is no evidence of warfare, and the reason they built on the sides of the mesa was to

keep warm when the climate cooled. Supposedly the Mesa Verde Anasazi left when the climate became too dry and the winters too long to support their agriculture. And because the population grew too large to be sustained by

their environment. The Anasazi men at Mesa Verde averaged about 5.5 feet tall, and the women around 5 feet--the same as Europeans of the era.

Their lifespans were the same also--30 to 40 years. As was stated earlier, the Anasazi in some cases had nicer dwellings than the Europeans, but they had no metal tools and

did not possess the wheel. They produced a complex culture in a “niche” environment, and their

descendents still survive, some of them living in homes very much like their ancestors’. As I viewed their artifacts, I thought less of how different they were from us and more of how much

we have in common with them. The stone building technology at Mesa Verde came from

the Chaco culture. As I stated earlier, the ranger also said there is no evidence of warfare, and the reason they built on the sides of the mesa was to

keep warm when the climate cooled. Supposedly the Mesa Verde Anasazi left when the climate became too dry and the winters too long to support their agriculture. And because the population grew too large to be sustained by

their environment. The Anasazi men at Mesa Verde averaged about 5.5 feet tall, and the women around 5 feet--the same as Europeans of the era.

Their lifespans were the same also--30 to 40 years. As was stated earlier, the Anasazi in some cases had nicer dwellings than the Europeans, but they had no metal tools and

did not possess the wheel. They produced a complex culture in a “niche” environment, and their

descendents still survive, some of them living in homes very much like their ancestors’. As I viewed their artifacts, I thought less of how different they were from us and more of how much

we have in common with them.

Sybil and I ate Navajo tacos at the little snack bar down the road from Cliff Palace, and as we ate it began to rain. We had hoped to hike into the afternoon, but the weather didn’t look like it

was going to clear up. So we decided to take a short hike to Spruce Tree House where there was a roofed undergroung kiva to go into. Well, this “short” hike turned out to be

a steep descent into a canyon and it also started to rain. Not only that,  because of all the

clouds it was getting dark early. I think Ed started to grumble about all this about halfway down. But I was adamant because I wanted to

see what a kiva was really like. There are several hundred cliff dwellings within the park and Spruce Tree House is the third largest.

About 100 people lived here in 114 rooms. While Ed took photos, I climbed down the ladder into the kiva. There wasn’t much there to

see, but it was still an experience to enter this room the same way people did 700 years ago. I guess they didn’t suffer much from arthritis. because of all the

clouds it was getting dark early. I think Ed started to grumble about all this about halfway down. But I was adamant because I wanted to

see what a kiva was really like. There are several hundred cliff dwellings within the park and Spruce Tree House is the third largest.

About 100 people lived here in 114 rooms. While Ed took photos, I climbed down the ladder into the kiva. There wasn’t much there to

see, but it was still an experience to enter this room the same way people did 700 years ago. I guess they didn’t suffer much from arthritis.

We drove down off the mesa in sporadic rain, through the town of Mancos, Colorado, and over a low mountain pass into Durango, where it was not raining. Durango is a tourist town now, with

a hip, international air about it, despite the lingering old-west flavor delivered by buggy and horse rentals, a few genuine cowboys, and a spiffy narrow-gauge steam railroad. People from all over

the world show up there to spend money in expensive shops, then go skiing, hunting, fishing, or adventuring. Sybil and I really liked the place. We stopped and drank a beer in the bar of a

century-old hotel, then walked down the street and had a gourmet meal in a restaurant that boasts of being 25 years old. The food was excellent. We took a stroll around downtown, but

soon drove out and found a reasonable motel to unwind in. Once we were inside it began to rain.

The weather was beautiful the next morning, so we drove back to

Mesa Verde, where we hiked and took photographs until early afternoon. The petroglyph trail is lengthy, taking you down into the canyon where you can experience the true beauty of the countryside.

There was a group of students and their professor at the petroglyph site, photographing, sketching, and measuring. I took a few shots, but

none of them came out, and I am uncertain as to the reason. The light was bad, but I had a tripod. We hiked fast because as the afternoon wore on it looked more and more like rain. The

last half hour or so we hiked in a light downpour. Despite our rush, this was the most beautiful hike of our trip. The weather was beautiful the next morning, so we drove back to

Mesa Verde, where we hiked and took photographs until early afternoon. The petroglyph trail is lengthy, taking you down into the canyon where you can experience the true beauty of the countryside.

There was a group of students and their professor at the petroglyph site, photographing, sketching, and measuring. I took a few shots, but

none of them came out, and I am uncertain as to the reason. The light was bad, but I had a tripod. We hiked fast because as the afternoon wore on it looked more and more like rain. The

last half hour or so we hiked in a light downpour. Despite our rush, this was the most beautiful hike of our trip.

We drove south, taking a different route to Farmington, where we stayed in the same hotel as before. Farmington is a rather plain, no frills town, but it has its own honest charm. The

motels are reasonable and clean, and the pace of life is unhurried. It seems to be a real Western town that provides services for real cowboys and Indians that live and work in

the vast northwest New Mexico landscape. This time we arrived early enough to explore  Hank’s Indian Pawn, which turned out to be primarily a boot and saddle

shop, but still maintains several display cases of genuine Indian jewelry. They said they don’t handle other kinds of merchandise any more. We waited

while the sales clerk sold some yarn to an old Indian woman. Sybil bought some nice silver and coral squash-blossom earrings. The few items that

appealed to me were too expensive, but we struck up an interesting conversation with Hank’s wife. She said sometimes the Indians Hank’s Indian Pawn, which turned out to be primarily a boot and saddle

shop, but still maintains several display cases of genuine Indian jewelry. They said they don’t handle other kinds of merchandise any more. We waited

while the sales clerk sold some yarn to an old Indian woman. Sybil bought some nice silver and coral squash-blossom earrings. The few items that

appealed to me were too expensive, but we struck up an interesting conversation with Hank’s wife. She said sometimes the Indians pawn stuff to keep their kids from selling it, even pawn their guns to keep their kids from using them to commit criminal acts. Hank’s quit taking guns in pawn because the guns had

a nasty habit of turning up again in criminal investigations. We also went into a much larger store across the street, which carried the

really expensive contemporary Indian jewelry, pottery, and rugs. The sheer quantity of silver jewelry in New Mexico boggles the mind.

There were dozens of other pawn shops in town that we would like to have visited. One interesting feature of the Four Corners area is the Indian trading post. These are

scattered all over and can be found in towns and remote crossroads. We didn’t have time (or the money) to stop in very many, but they buy arts and crafts from the Indians and

supply basic necessities. Some of these have been in the same family for generations. pawn stuff to keep their kids from selling it, even pawn their guns to keep their kids from using them to commit criminal acts. Hank’s quit taking guns in pawn because the guns had

a nasty habit of turning up again in criminal investigations. We also went into a much larger store across the street, which carried the

really expensive contemporary Indian jewelry, pottery, and rugs. The sheer quantity of silver jewelry in New Mexico boggles the mind.

There were dozens of other pawn shops in town that we would like to have visited. One interesting feature of the Four Corners area is the Indian trading post. These are

scattered all over and can be found in towns and remote crossroads. We didn’t have time (or the money) to stop in very many, but they buy arts and crafts from the Indians and

supply basic necessities. Some of these have been in the same family for generations.

The next morning, May 25, we got up and drove east to Taos through

some of the most beautiful land in New Mexico. We drove through the Gobernador Canyon, the Vaqueros Canyon, then up through Dulce and Lumberton and over the continental divide. Chama is a beautiful little

resort town with several bed and breakfasts. Some artists have apparently taken up residence there. The next morning, May 25, we got up and drove east to Taos through

some of the most beautiful land in New Mexico. We drove through the Gobernador Canyon, the Vaqueros Canyon, then up through Dulce and Lumberton and over the continental divide. Chama is a beautiful little

resort town with several bed and breakfasts. Some artists have apparently taken up residence there.  There were very few people

there, but it was early for their tourist season. We ate lunch and then investigated the narrow-gauge railroad station across the street. The Cumbres and Toltec Railroad has at least two

functional steam engines (and a couple of spares being parted out), along with numerous freight and passenger cars. I thought I’d like to ride it sometime. There were very few people

there, but it was early for their tourist season. We ate lunch and then investigated the narrow-gauge railroad station across the street. The Cumbres and Toltec Railroad has at least two

functional steam engines (and a couple of spares being parted out), along with numerous freight and passenger cars. I thought I’d like to ride it sometime.

The road from Chama to Taos over the San Juan Mountains through the Carson National Forest is beautiful and not well traveled, at least not at this time of the year. Before we

got over the top, we ran into sleet and snow flurries...but not enough to slow us down appreciably. Still it was a novelty to those of us from Texas. It continued cloudy and rainy when we got to Taos.

I had heard a lot about Taos so I had to see it for myself. It looked to me like a miniature Santa Fe, but was even more congested with tourist traffic. The infrastructure of streets and

roads was not designed for the quantity of traffic it now carries. We stayed in a rather expensive motel (half-price thanks to my motor club), but it wasn’t anything special. I

read about even more expensive ones there that come with your own kiva. Taos is supposed to be a spiritual place, but I fear that materialism has won out. However, we

only stayed for a day and a half, which is too short a time to judge any place. I visited the Kit Carson Museum which is in the house he and his wife maintained in Taos. Taos used

to be an important rendezvous point and trading post for the early mountain men and trappers. The museum is modest but it does help you get the feeling of what those days

were like. Taos was also the first destination on the trade route from St. Louis, Missouri, that came to be known as the Santa Fe Trail, but it never became the political and

commercial center that Santa Fe did. Again there are plenty of stores here for the tourist shopper, as well as many artists.

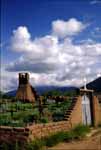

The next day we visited Taos Pueblo. The pueblo consists of two adobe dwelling complexes separated by a fast running

stream that flows out of the mountains. The pueblo still exists much as it was described by the first Spanish explorers. As with the other pueblos, there is a camera fee and no commercial

photography allowed without prior arrangement The next day we visited Taos Pueblo. The pueblo consists of two adobe dwelling complexes separated by a fast running

stream that flows out of the mountains. The pueblo still exists much as it was described by the first Spanish explorers. As with the other pueblos, there is a camera fee and no commercial

photography allowed without prior arrangement . The cemetary

is next to the ruins of the old adobe San Geronimo church which was built by the Indians under the the direction of the Spanish missionaries in

1619. It was destroyed in the 1680 Pueblo Revolt but rebuilt in 1706. However, in retaliation for the murder of the territorial governor in

1847, the U.S. Army bombarded the church where the Indians had barracaded themselves. The church was destroyed and 150 men, women and children were killed. The Indians have let the ruins remain as a

memorial to their dead and a constant reminder of the injustice they have suffered at the hands of the white man. . The cemetary

is next to the ruins of the old adobe San Geronimo church which was built by the Indians under the the direction of the Spanish missionaries in

1619. It was destroyed in the 1680 Pueblo Revolt but rebuilt in 1706. However, in retaliation for the murder of the territorial governor in

1847, the U.S. Army bombarded the church where the Indians had barracaded themselves. The church was destroyed and 150 men, women and children were killed. The Indians have let the ruins remain as a

memorial to their dead and a constant reminder of the injustice they have suffered at the hands of the white man.

I asked an old Indian man in the parking lot at Taos Pueblo if I could use my

tripod, and he said yes, but when we bought our tickets I was told it was forbidden, so I took all my camera equipment back to the Jeep in disgust. I

didn’t regret this, since I didn’t find the pueblo particularly I asked an old Indian man in the parking lot at Taos Pueblo if I could use my

tripod, and he said yes, but when we bought our tickets I was told it was forbidden, so I took all my camera equipment back to the Jeep in disgust. I

didn’t regret this, since I didn’t find the pueblo particularly compelling, though

I did take a few shots with Sybil’s Canon. I saw an old woman on top of the pueblo replastering the walls with mud. Later I heard her hollering at a tourist woman: “Don’t

take my picture! Don’t you do it! I’m not here for you to take my picture!” The woman yelled back that she was

photographing a ladder, but the old Pueblo woman didn’t believe her for a minute. Many of the dwellings at Taos Pueblo have been converted into

stores; most of the Indians live elsewhere and only drive in to sell their wares. compelling, though

I did take a few shots with Sybil’s Canon. I saw an old woman on top of the pueblo replastering the walls with mud. Later I heard her hollering at a tourist woman: “Don’t

take my picture! Don’t you do it! I’m not here for you to take my picture!” The woman yelled back that she was

photographing a ladder, but the old Pueblo woman didn’t believe her for a minute. Many of the dwellings at Taos Pueblo have been converted into

stores; most of the Indians live elsewhere and only drive in to sell their wares.

|