|

After leaving Acoma Pueblo we drove to an area of ancient lava flows known as El Malpais, off highway 117 South of Grants, New

Mexico, where we took some photographs. This lava flow filled the whole valley and apparently happened only about 1500 years ago or so. The volcano that erupted was barely discernable in

the distance and it didn’t seem possible it was responsible for all that lava. Only some shrubs have managed to grow on the lava field and there are large patches of bare black lava stone. Then we proceeded to La Ventana natural arch. It was late

in the afternoon when we arrived. The sun was low on the Western horizon, and the arch was perfectly illuminated, so Sybil and I hiked After leaving Acoma Pueblo we drove to an area of ancient lava flows known as El Malpais, off highway 117 South of Grants, New

Mexico, where we took some photographs. This lava flow filled the whole valley and apparently happened only about 1500 years ago or so. The volcano that erupted was barely discernable in

the distance and it didn’t seem possible it was responsible for all that lava. Only some shrubs have managed to grow on the lava field and there are large patches of bare black lava stone. Then we proceeded to La Ventana natural arch. It was late

in the afternoon when we arrived. The sun was low on the Western horizon, and the arch was perfectly illuminated, so Sybil and I hiked  up to it, taking photographs all the way. When we got beneath the arch, we realized we could see the moon in the sky

above. We met another couple who were also hiking there and driving a new Jeep Cherokee like Sybil’s, albeit theirs had 4-wheel

drive. They were obviously retired and enjoying themselves. We conversed with them for a while before leaving, and saw them again at Chaco Canyon. up to it, taking photographs all the way. When we got beneath the arch, we realized we could see the moon in the sky

above. We met another couple who were also hiking there and driving a new Jeep Cherokee like Sybil’s, albeit theirs had 4-wheel

drive. They were obviously retired and enjoying themselves. We conversed with them for a while before leaving, and saw them again at Chaco Canyon.

I shot my first roll of Ilford SFX 200 extended-red- I shot my first roll of Ilford SFX 200 extended-red- sensitivity film at

the arch, exposing it at EI 100--with a number 25 red filter on the 80mm lens and a Wratten G orange filter on the 43mm. The SFX is not as dramatic an infrared film as Kodak or Konica,

but it did produce some very subtle infrared effects, particularly with the red filter. Look at the foliage on the tree in the photograph on the left. Some of the subtle

detail is difficult to capture with a scanner, and I can’t wait to get these negatives in the enlarger and see how they will print. sensitivity film at

the arch, exposing it at EI 100--with a number 25 red filter on the 80mm lens and a Wratten G orange filter on the 43mm. The SFX is not as dramatic an infrared film as Kodak or Konica,

but it did produce some very subtle infrared effects, particularly with the red filter. Look at the foliage on the tree in the photograph on the left. Some of the subtle

detail is difficult to capture with a scanner, and I can’t wait to get these negatives in the enlarger and see how they will print.

From the arch we drove North up to Grants, New Mexico, then Northwest on 547 into the Cibola National

Forest toward Mt. Taylor. We camped in an otherwise deserted national forest campground, and made burgers out of the ground buffalo meat we had bought in Santa

Fe--it tasted just like lean beef. I slept like a rock, but Sybil reports that coyotes howled in the night. It got pretty chilly that night (May 20), though it didn’t freeze.

The next morning I got up early and built a fire which took the chill off us until the sun could rise. I drank tea and Sybil drank coffee, then we broke

camp and drove into Grants for breakfast. Grants had been descended upon by hundreds of bikers in full leathers (most of them in their 40’s to 60’s and riding Harleys) on their way to

Washington, D.C., to remind the government about the plight of our MIA’s in Vietnam. We encountered several hundred of them buying gas at the convenience store. We bought supplies

in Grants before heading for Chaco Canyon. From the arch we drove North up to Grants, New Mexico, then Northwest on 547 into the Cibola National

Forest toward Mt. Taylor. We camped in an otherwise deserted national forest campground, and made burgers out of the ground buffalo meat we had bought in Santa

Fe--it tasted just like lean beef. I slept like a rock, but Sybil reports that coyotes howled in the night. It got pretty chilly that night (May 20), though it didn’t freeze.

The next morning I got up early and built a fire which took the chill off us until the sun could rise. I drank tea and Sybil drank coffee, then we broke

camp and drove into Grants for breakfast. Grants had been descended upon by hundreds of bikers in full leathers (most of them in their 40’s to 60’s and riding Harleys) on their way to

Washington, D.C., to remind the government about the plight of our MIA’s in Vietnam. We encountered several hundred of them buying gas at the convenience store. We bought supplies

in Grants before heading for Chaco Canyon.

The last time I was in Chaco Canyon it was the middle of June, 1990,

and the weather was very hot. This time, on May 21, 1999, it wasn’t quite so bad--but we were careful to stay out of the sun during the

hottest part of the day, and we both drank a lot of water. That afternoon Sybil and I went to the visitor center and enjoyed the air conditioning while we watched a video on Chaco. Chaco Canyon is

the center of an ancient culture whose people are known as the The last time I was in Chaco Canyon it was the middle of June, 1990,

and the weather was very hot. This time, on May 21, 1999, it wasn’t quite so bad--but we were careful to stay out of the sun during the

hottest part of the day, and we both drank a lot of water. That afternoon Sybil and I went to the visitor center and enjoyed the air conditioning while we watched a video on Chaco. Chaco Canyon is

the center of an ancient culture whose people are known as the  Anasazi. The word Anasazi is

Navajo for “the old ones” or “the old enemy.” However, archaeologists believe that by the time the Navajo and their cousins

the Apache arrived in the area, the heyday of the Anasazi was long past. There is no evidence that the Navajo or Apache ever warred with the Anasazi, but there is also no denying that the word Anasazi

has some negative connotations. The Navajo have strong beliefs about ghosts. Maybe that’s where the “old enemy” comes from. Anasazi. The word Anasazi is

Navajo for “the old ones” or “the old enemy.” However, archaeologists believe that by the time the Navajo and their cousins

the Apache arrived in the area, the heyday of the Anasazi was long past. There is no evidence that the Navajo or Apache ever warred with the Anasazi, but there is also no denying that the word Anasazi

has some negative connotations. The Navajo have strong beliefs about ghosts. Maybe that’s where the “old enemy” comes from.

The earliest and largest settlement at Chaco Canyon, called Pueblo  Bonito, was built in three

distinct phases from 850 to 1150 CE. What I came away from the video with was a sense of the extent and accomplishments of a complex civilization that stretched from Hovenweep and Mesa Verde

in the North to Paquime, in the modern state of Chihuahua, Mexico, to the South. The ancient roads linking these settlements connect like spokes to Chaco, and there is clear evidence of trade with Mexico

and possibly South America. Bonito, was built in three

distinct phases from 850 to 1150 CE. What I came away from the video with was a sense of the extent and accomplishments of a complex civilization that stretched from Hovenweep and Mesa Verde

in the North to Paquime, in the modern state of Chihuahua, Mexico, to the South. The ancient roads linking these settlements connect like spokes to Chaco, and there is clear evidence of trade with Mexico

and possibly South America.

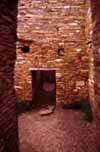

The Chacoans built stone houses that were by and large

superior to the homes of Europeans in the same era. The walls were built of two courses of shaped stone, with rubble fill in the middle. Early walls used no mortar, but were chinked and

fitted very carefully; later walls used mud mortar, but all were originally plastered over and painted. Parts of Pueblo Bonito, the largest and earliest building in Chaco Canyon, were 3 and 4

stories high--requiring sophisticated engineering skills to build. The rooms were small (12 x 14 ft. or less--much less) and accessed primarily from a ladder

through the roof (I didn’t understand this until I read the guide--a great many of the rooms in the various settlements at Chaco Canyon don’t have doors). A whole family would live in one or

two of these rooms. The Pueblo people of Chaco Canyon fed their population by building a system of canals and irrigation channels to get rainwater to their crops. They probably grew

corn, beans, squash and cotton, since these were the crops that the pueblos were growing when the Spaniards arrived. At one time, the entire canyon is thought to have been cultivated. The Chacoans built stone houses that were by and large

superior to the homes of Europeans in the same era. The walls were built of two courses of shaped stone, with rubble fill in the middle. Early walls used no mortar, but were chinked and

fitted very carefully; later walls used mud mortar, but all were originally plastered over and painted. Parts of Pueblo Bonito, the largest and earliest building in Chaco Canyon, were 3 and 4

stories high--requiring sophisticated engineering skills to build. The rooms were small (12 x 14 ft. or less--much less) and accessed primarily from a ladder

through the roof (I didn’t understand this until I read the guide--a great many of the rooms in the various settlements at Chaco Canyon don’t have doors). A whole family would live in one or

two of these rooms. The Pueblo people of Chaco Canyon fed their population by building a system of canals and irrigation channels to get rainwater to their crops. They probably grew

corn, beans, squash and cotton, since these were the crops that the pueblos were growing when the Spaniards arrived. At one time, the entire canyon is thought to have been cultivated.

Chaco was apparently a “ceremonial center.” We should be skeptical of this appellation because it has so many potentially misleading connotations, but it is used for lack of a better term

. All the “great houses” have “great kivas”-- large, round subterranean rooms used for

“ceremonial” purposes. Kivas typically have a stone bench around the periphery, a firebox protected from the wind of the floor-vent by a flat stone deflector, and four  pillars that support the roof. The great kivas at Chaco also contain wall niches and an additional

vent that runs beneath the floor. Kivas are known to be descended from the pit-houses of an earlier era (circa 400 CE). A pit-house is a circular pit dug

three or four feet deep and 20 to 30 feet in diameter, with flat stones placed all around the periphery to serve as walls, and four pillars set so as to support

a roof that sloped up to a central square hole which served as a vent for smoke. The roof was covered over with branches and earth, and an

entranceway was dug that led one down and back up into the house. pillars that support the roof. The great kivas at Chaco also contain wall niches and an additional

vent that runs beneath the floor. Kivas are known to be descended from the pit-houses of an earlier era (circa 400 CE). A pit-house is a circular pit dug

three or four feet deep and 20 to 30 feet in diameter, with flat stones placed all around the periphery to serve as walls, and four pillars set so as to support

a roof that sloped up to a central square hole which served as a vent for smoke. The roof was covered over with branches and earth, and an

entranceway was dug that led one down and back up into the house.

We don’t know if kivas were the exclusive province of men at Chaco

and other Anasazi sites. They certainly are today among the Pueblo Indians, but since it is known that kivas evolved from earlier pit-houses there must have been a time when they were shared by all.

Later in our trip, the guide at Mesa Verde would be careful to tell us that the kivas were used by whole families--he didn’t say how this

was deduced, but I assume it was by careful archaeological sifting of the sites. We don’t know if kivas were the exclusive province of men at Chaco

and other Anasazi sites. They certainly are today among the Pueblo Indians, but since it is known that kivas evolved from earlier pit-houses there must have been a time when they were shared by all.

Later in our trip, the guide at Mesa Verde would be careful to tell us that the kivas were used by whole families--he didn’t say how this

was deduced, but I assume it was by careful archaeological sifting of the sites.

In all our travel, little mention was made of war or violence. In fact, at Mesa Verde our guide (a park ranger, who was really an interesting guy) denied that the cliff houses were built for defense

--he maintained the Anasazi left the top of the mesa because it got too cold there. But the May/June 1999 issue of Discovering Achaeology magazine tells a somewhat different story,

assuming a climate of ongoing violence and implying that the people of Mesa Verde needed a good defensive position. There is also some evidence for cannibalism among the Anasazi at

about half (or possibly one quarter) of the sites, including Chaco, over the entire geographical range of the culture, from 900 to 1300 CE. Evidence includes finds of multiple human skeletons

that have been torn apart and discarded like garbage, arm and leg bones that have been broken for their marrow, skulls that appear to have been cooked and broken open, and cut marks on

human bones that indicate they were butchered. Paul Horgan (Great River: The Rio Grande in North American History) reported a pueblo myth or story about a cannibal giant that once

lived in a cave on the north side of the black mesa near San Ildefonso Pueblo. “His cave was connected with the interior of the vast, houselike mesa by tunnels which took him to

his rooms. His influence upon the surrounding country was heavy. Persons did the proper things to avoid  being caught and eaten by him.” A great many people disagree with

these interpretations, not the least of which are the modern Pueblo peoples, but also a number of other people, including scholars, with (supposedly) no axe to grind. At the time of the arrival of the Spaniards, the Pueblo

people were apparently very peace-loving and non-warlike. They received the Spaniards with gifts and courtesy until the Spaniards violated their trust by raping their women and imprisoning their

leaders without cause. However, some southern Pueblo groups apparently were not friendly with those in the northern reaches. being caught and eaten by him.” A great many people disagree with

these interpretations, not the least of which are the modern Pueblo peoples, but also a number of other people, including scholars, with (supposedly) no axe to grind. At the time of the arrival of the Spaniards, the Pueblo

people were apparently very peace-loving and non-warlike. They received the Spaniards with gifts and courtesy until the Spaniards violated their trust by raping their women and imprisoning their

leaders without cause. However, some southern Pueblo groups apparently were not friendly with those in the northern reaches.

There are definite Anasazi connections with the early civilizations of Mexico and Central America. Trade links are firmly established: the

Chacoans and other Pueblo peoples imported live macaws, and feathers of many other birds, from Mexico and South America, as well as turquoise and metal objects from various distant places. A

few rare skulls have been found at Anasazi sites with filed teeth, a decoration which was much more common among the residents of what is now Mexico. Christy

G. Turner II (professor of archaeology at Arizona State University) has suggested that these individuals were from Mexico and that their cultural influence was significant in the climate of

violence that pervaded the Anasazi world. There are definite Anasazi connections with the early civilizations of Mexico and Central America. Trade links are firmly established: the

Chacoans and other Pueblo peoples imported live macaws, and feathers of many other birds, from Mexico and South America, as well as turquoise and metal objects from various distant places. A

few rare skulls have been found at Anasazi sites with filed teeth, a decoration which was much more common among the residents of what is now Mexico. Christy

G. Turner II (professor of archaeology at Arizona State University) has suggested that these individuals were from Mexico and that their cultural influence was significant in the climate of

violence that pervaded the Anasazi world.

Interestingly, many of the pit-houses of the Anasazi appear to have been burned, and there are a number of cases where entire Pueblo villages were burnt. Pit houses (and  stone or adobe pueblos) are rather difficult to set afire--only the wooden beams of the ceilings

are flammable, and they are typically covered with a layer of earth or mud. William H. Walker (assistant professor of Anthropology at New Mexico

State University) believes that the only logical explanation for the systematic burning of Anasazi habitations is the intent to destroy witches. Many

indigenous peoples believe implicitly in witches and ghosts, even today. Walker (in his article “Witchcraft” in Discovering Archaeology, May/June 1999, p. 54) says: “As recently as 1945, a Cocopa sorcerer was locked in his house and burned to death.” As best I can tell from a search on the Internet, the

Cocopa people live in Southern Arizona, and Baja California (Mexico). stone or adobe pueblos) are rather difficult to set afire--only the wooden beams of the ceilings

are flammable, and they are typically covered with a layer of earth or mud. William H. Walker (assistant professor of Anthropology at New Mexico

State University) believes that the only logical explanation for the systematic burning of Anasazi habitations is the intent to destroy witches. Many

indigenous peoples believe implicitly in witches and ghosts, even today. Walker (in his article “Witchcraft” in Discovering Archaeology, May/June 1999, p. 54) says: “As recently as 1945, a Cocopa sorcerer was locked in his house and burned to death.” As best I can tell from a search on the Internet, the

Cocopa people live in Southern Arizona, and Baja California (Mexico).

After watching the movie at the visitor center, we hiked a short distance to

photograph some petroglyphs, then retired to our camp site to wait out the afternoon heat. When the worst of the heat was over, we drove down the

road and toured and photographed the Chetro Ketl and Pueblo Bonito sites. Pueblo Bonito is the largest of the sites, and is matched in age only by the Una

Vida site, both dating from approximately 850 CE. At one time, archaeologists estimated that 1,000 or more people lived at Pueblo Bonito,

but recent speculation puts the total between 50 and 100, based on a study of the number of rooms that were actually liveable and the number of rooms

used for storage and ceremony. Current thought is that Pueblo Bonito was a seasonal gathering place for trade. Estimates for the population of the entire canyon at its height were once

between 20,000 and 30,000, but have been revised down to between 4,000 and 5,000. After watching the movie at the visitor center, we hiked a short distance to

photograph some petroglyphs, then retired to our camp site to wait out the afternoon heat. When the worst of the heat was over, we drove down the

road and toured and photographed the Chetro Ketl and Pueblo Bonito sites. Pueblo Bonito is the largest of the sites, and is matched in age only by the Una

Vida site, both dating from approximately 850 CE. At one time, archaeologists estimated that 1,000 or more people lived at Pueblo Bonito,

but recent speculation puts the total between 50 and 100, based on a study of the number of rooms that were actually liveable and the number of rooms

used for storage and ceremony. Current thought is that Pueblo Bonito was a seasonal gathering place for trade. Estimates for the population of the entire canyon at its height were once

between 20,000 and 30,000, but have been revised down to between 4,000 and 5,000.

The next morning we got up early and hiked up to the top of the mesa. From there we could photograph the entire expanse of Pueblo Bonito and Chaco Canyon. We  hiked to Pueblo Alto, which is up on the highest point of the Mesa. Some scholars theorize that

the Anasazi could use signal fires to communicate with their far-flung outposts up to 25 miles away. There are a number of other sites that can

see a fire built at Pueblo Alto. By the time we hiked down off the mesa the sky was lowering and threatening rain. We got sprinkled on, but didn’t

encounter any serious rain driving out of Chaco Canyon. (Access from both the south and the north is via 15 miles of gravel roads. Though they were well-graded for the most part, the roads become

impassable during the rainy season, so we were told.) hiked to Pueblo Alto, which is up on the highest point of the Mesa. Some scholars theorize that

the Anasazi could use signal fires to communicate with their far-flung outposts up to 25 miles away. There are a number of other sites that can

see a fire built at Pueblo Alto. By the time we hiked down off the mesa the sky was lowering and threatening rain. We got sprinkled on, but didn’t

encounter any serious rain driving out of Chaco Canyon. (Access from both the south and the north is via 15 miles of gravel roads. Though they were well-graded for the most part, the roads become

impassable during the rainy season, so we were told.)

We had thought we might camp in the Bisti badlands, but the skies continued to be dark and we

had occasional drizzle as we drove through the area. Plus, the Bisti wilderness is very forbidding

--it didn’t look inviting to say the least. Sybil and I were hot and dusty and hadn’t had a shower

in two days, so we drove up to Farmington and got a motel room near the airport. We arrived late in the afternoon on Saturday, May 22. Farmington has a lot of pawn shops, and we were

curious to see what they had for sale, but they were all closed by the time we got there.

|