|

Mauser Pistols:

1910, 1914, WTP, HSc

by Ed Buffaloe and Burgess Mason III

Part IV: The HSc

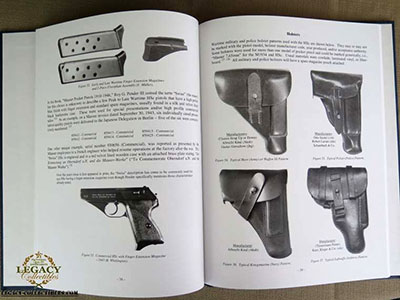

Detailed information about the development of the Mauser HSc pistol can be found in two excellent sources: Weaver, Speed, and Schmid’s Mauser Pistolen and Burnham and Theodore’s The Mauser HSc Pistol.

This article is particularly indebted to the latter book. With the advent of the Walther PP pistol in 1929, most existing single-action designs were superseded. Other weapons manufacturers needed to offer

double-action designs to stay competitive, and Mauser was no exception.

There is no need for us to repeat the entire story here, but suffice it to say that the HSc development time was lengthy, about five years from start to completed product (1934-1938). There is

probably no single reason that development took so long, but factors include: the youth of the engineer in charge of the project, Alexius Seidel, who was 25 years old when the project was

initiated; the fact that he was required not to infringe any existing patents, particularly those of the litigious Walther company; and the fact that the team was tasked to build two guns at once, a 9 mm

Parabellum locked breech pistol and a 7.65 mm Browning unlocked breech pistol. Over the course of those five years at least 13 documented prototype pistols were made and tested, nine of

which were chambered in 9 mm Parabellum and four in 7.65 mm Browning.

The HS in HSc stands for “Hahn Selbstspanner,” literally “hammer self-spanning,” but generally

translated as “self-cocking hammer.” The “c”, according to August Weiss, means that it is the third production pistol with an external hammer, following the Mauser C96 and the Nickl pistol of 1922.

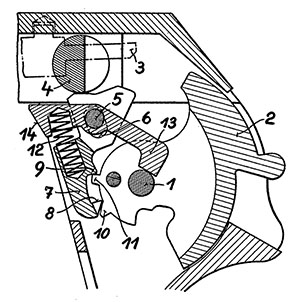

The Patents

A large number of patents were filed between 1934 and 1938 in multiple countries. We will try to

deal only with the ones related in some way to the Mauser HSc, and for brevity’s sake we will only list German and U.S. patents, in order by date of filing.

- German patent 634577, filed 21 August 1934 and granted 13 August 1936. This patent, attributed to Ernst Altenberger, is for the magazine safety mechanism.

- German patent 670241, filed 21 August 1934 and granted 22 December 1938. This patent of a design by Ernst Altenberger is the first to show a safety that moves the firing pin upward

and out of the path of the hammer.

- German patent 679683, filed 7 May 1935 and granted 20 July 1939. This is Ernst Altenberger’s patent for the barrel retention and release mechanism used in many of the

prototypes as well as in the HSc. The idea may have come from the barrel retention mechanism of the WTP, which places the mechanism behind the trigger and requires an

extension of the frame behind the trigger guard. The new method is more elegant in that the mechanism is mostly hidden from view and is spring-loaded. It requires the trigger guard to

be extended toward the front rather than the rear.

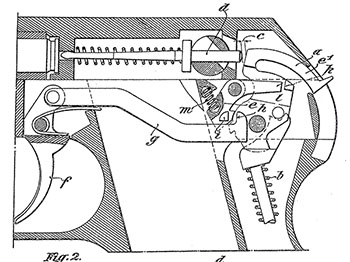

- German patent 671000, filed 7 June 1935 and granted 5 January 1939. This is Alex Seidel’s patent for the basic trigger and sear mechanism.

- German patent 640721, filed 17 July 1935 and granted 17 December 1936. This patent describes the disconnector.

- German patent 680451, filed 14 May 1935 and granted 10 August 1939. This is Alex Seidel’s patent for the trigger bar and magazine safety.

- German patent 688511, filed 14 May 1934 and granted 1 February 1940. This is a patent for a magazine release, tensioned by the main spring which surrounds the hammer strut, although

the hammer is not shown in the patent drawing.

-

German patent 673766, filed 18 July 1935 and granted 9 March 1939. This is a further elaboration of German patent 670241, the safety mechanism that moves the firing pin out of the path of the hammer.

- German patent 689183, filed 7 August 1935 and granted 22 February 1940. This is Alex Seidel’s patent for the trigger and double-action lockwork mechanisms. This patent

shows an early hammer design in which the hammer opening is sealed whether cocked or uncocked, preventing dirt and debris from getting into the mechanism.

- U.S. patent 2,117,826, filed 20 August 1935 and granted 17 May 1938. This is the equivalent of German patent 688511, but this patent is

attributed to Alex Seidel and shows the hammer and sear mechanism. “...the push rod, the hammer spring and the magazine holder are combined into a unit, the insertion and removal of

which are thus simplified.” The patent only mentions the hammer in passing, but states that the magazine release is specifically designed to prevent dirt and debris from getting into the magazine well.

- U.S. patent 2,138,213, filed 20 August 1935 and granted 29 November 1938. This is the equivalent of German patents 671000 and 689183. The patent drawings actually show two

different pistols, the second of which is essentially the HSc prototype.

- U.S. patent 2,177,227, filed 20 August 1935 and granted 24 October 1939. This patent describes the disconnector, and is the equivalent of German patent 640721. It specifically

references the previous patent (2,138,213 above) filed on the same date.

- U.S. patent 2,110,317, filed 20 August 1935 and granted 8 March 1938. This patent combines German patents 673766, and 691007. It is Ernst Altenberger’s patent for the safety

and hammer. “...the hammer is equipped with an extension opposite its striking face, and a cocking lug on the extension. The extension occupies an opening in the casing which

completely encloses the hammer, and the opening is closed by the extension in the cocked and uncocked positions...”

-

German patent 691007, filed 24 September 1935 and granted 18 April 1940. This is Ernst Altenberger’s patent for the hammer design alone.

- U.S. patent 2,107,359, filed 9 December 1935 and granted 8 February 1938. This patent is for the same barrel retention and release mechanism shown in German patent 679683, but is different in that it

shows a rotating barrel like that used in the Nickl prototypes. The applicant is Ernst Altenberger, assignor to Mauser-Werke.

- German patent 691840, filed 21 August 1938 and granted 9 May 1940. This is Alex Seidel’s final patent for the safety mechanism. It specifically

references his earlier German patents 670241 and 673766. The patent drawings include details of the hammer and sear as they were actually manufactured. The final hammer design differs from

the original design patented by Altenberger.

The HSc Design

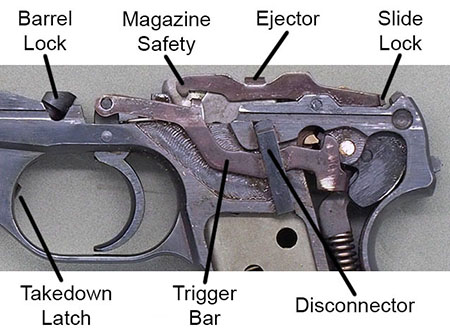

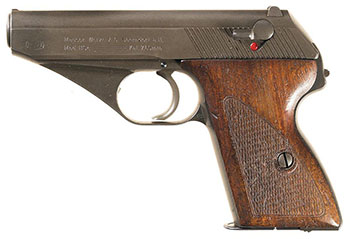

The Mauser HSc breaks down into three modules: the slide, the frame, and the magazine. The

magazine is pretty standard fare, with the exception that the follower is designed to lock the slide open when the magazine is empty and so is very solidly built. The slide assembly includes the

barrel and concentric recoil spring, the firing pin, and the patented safety lever which, when engaged, moves the firing pin up above the reach of the hammer. The slide has a milled channel on

top which contains the fixed front sight and the drift-adjustable dovetailed rear sight. The frame is elegantly designed with an ergonomic curved backstrap and a trigger guard that extends at an angle

upward toward the front of the gun and houses the barrel release mechanism. This barrel release allows the HSc to be disassembled in mere seconds.

The hammer pivots on a pin and its upward extension pulls the trigger bar forward. The trigger bar (or connector or transfer bar) runs on the left side of the gun. The disconnector

is a separate piece fitted over the trigger bar, but tensioned by the trigger spring. In double action mode, the lower extension at the rear of the trigger bar pulls the lower portion of the hammer forward, drawing the

upper portion backward, then an upward extension at the rear of the trigger bar engages a protrusion on the left side of the sear to release the hammer and ignite the cartridge. The

underside of the hammer has two lugs or detents, one of which serves as the half-cock detent and the second as the full-cock detent. The lower extension of the sear serves as a pawl to engage

these hammer detents. After the first cartridge is fired, the recoiling slide moves the hammer to its full cock position. The rear portion of the hammer pushes the trigger bar forward, which forces

the trigger to the rear, indicating to the shooter that the hammer is cocked, and making the single-action throw of the trigger quite short.

A second bar sits above the trigger bar on the left side of the gun and serves three purposes:

magazine safety, magazine ejector, and slide lock. The bar pivots on a pin. When the magazine is removed, the forward portion of this bar descends and locks the trigger bar, preventing the trigger

from being pulled, and the rear portion of the bar moves upward to lock the slide. When the magazine is inserted in the frame it pushes the forward portion of this bar upward, freeing the

trigger, and the rear portion down, unlocking the slide. A tab on this bar protrudes two millimeters to the right and serves as the magazine ejector.

The main spring at the rear, behind the magazine, tensions both the hammer at the top and the magazine release at the bottom of the grip. As on earlier Mauser designs, the only screws are to

hold the grip plates in place. Everything else is fitted together and held in place by pins or by spring tension.

Functionality

With the hammer down and the safety off, the first shot can be fired double action. After the first

shot is fired the hammer is cocked automatically by the recoiling slide and subsequent shots are fired in single action mode. The safety lever locks the slide and prevents the hammer from being

cocked. The magazine safety locks the trigger and prevents the hammer from being cocked. If the hammer is already cocked when the safety is engaged, pulling the trigger will cause the hammer to

fall, though the gun will not fire because the firing pin is above the path of the hammer. If the slide is locked open with the safety engaged, inserting a fresh magazine will cause the slide to close and

the hammer to fall on guns prior to approximately serial number 860000. After approximately serial number 860000, the hammer will remain cocked when the slide is closed with the safety on.

Production Dates and Variations

Page 254 of Mauser Pistolen shows a photograph, likely from an original glass plate negative, of

a pre-production HSc prototype. It is nearly identical to the early production gun save for the round rear-sight and the slide inscription, which in addition to the company name reads “Pistole Cal. 7,65mm.” On page 263 is another unserialled pre-production gun with a dovetailed rear sight, a

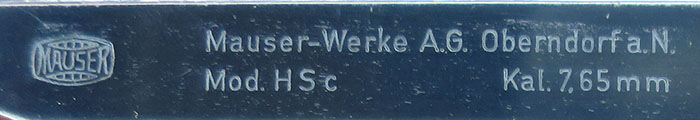

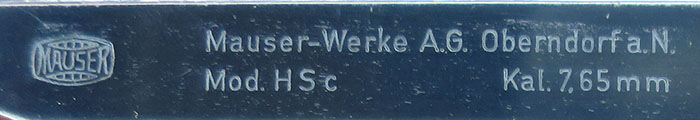

low grip screw, the Mauser powder barrel logo stamped at the top of the walnut grip plates, and a slide inscription that reads:

Mauser-Werke A.G. Oberndorf a.N.

H.S.c. 7,65 mm

According to Weaver, Speed, and Schmid, in their book Mauser Pistolen, the Mauser HSc was ready for production by the end of 1938, but Mauser was required to certify to the government that

the pistol “was an urgent military need.” But because the pistol was (at the time) intended for police and civilian rather than military use, the Nazi government withheld permission to begin

manufacture. Additionally, the fact that Fritz Walther was a strong Nazi supporter, and his company had the contract for the standard military pistol (the Walther P38), may have meant that

Walther was given preferential treatment. Tooling up and organizing production steps began in 1939, as documented in Mauser Pistolen, but Mauser was not allowed to actually begin production until late 1940.

Serial numbers begin at 700001. According to Burnham and Theodore in their 2015 book The Mauser HSc Pistol, the first production gun was test fired on 19 September 1940. Production

began in earnest in December 1940. Changes were made over time to the finish and to the slide inscription, but with a few very minor exceptions which will be discussed below, all HSc pistols

produced during and immediately after the war are mechanically identical.

Burnham and Theodore state that wartime production of the HSc can be “generally grouped within

four time periods derived from an extensive database of information.” To their four groups we have added a fifth for immediate post-war production:

-

Early War Production: Dec. 1940 - Aug. 1942

(SN 700001 - 787445)

- Transitional Production: Aug 1942 - Nov. 1942

(SN 787446 - 800445)

- Peak War Production: Nov. 1942 0 Aug. 1943

(SN 800446 - 852245)

- Late War Production: Aug. 1943 - Apr. 1945

(SN 852246 - 951939)

- Post-War French Production: May 1945 - Jun. 1946

(SN 951940 - 971239)

Jan C. Still, in his 1986 book Axis Pistols Volume II, established a method of categorizing HSc pistols according to the acceptance marks used by the

military and police stamped on the left side of the trigger guard. These categories are:

- Commercial: By law, all pistols that were produced during the war will typically have the standard government nitro proof mark stamped

on frame, slide and barrel, which was the eagle over N. The left side of the trigger guard will typically be blank on commercial pistols. All guns provided to the military and police should have the nitro proof,

though very late in the war the proof house was closed and some guns may not have been proofed.

- Army: HSc pistols used by the German army are marked with a Waffenamt acceptance stamp in the form of an eagle over 655, eagle over 135, or eagle over WaA135 on the rear of the left trigger guard where it meets the frame.

- Navy: HSc pistols used by the German navy (Kriegsmarine) are marked with a Marinewaffenamt acceptance stamp in the form of an eagle over MIII/8 on the rear of the left trigger guard where it meets the frame ane/or an eagle holding a circled swastika over the letter M property mark

on the front grip strap.

- Police: HSc pistols used by the German police are marked, on the rear of the left trigger guard where it meets the frame, with an eagle over a circled X, with an L or an F below and to the right.

A longtime HSc collector adds that the German army and police had inspectors at the Mauser factory to examine pistols and apply acceptance marks.

Early War Production

The earliest pistols produced are known as the Low Grip Screw HSc. Mauser originally positioned the grip screw quite low on the grip, but decided very early in production to move it up by

about 3/4 inch. Apparently they already had 1345 frames made with the low screw hole, so they went ahead and finished these guns, as demand was high at the beginning of the war. Today the low grip

screw HSc is a highly sought-after collector item. Weaver, Speed, and Schmid describe these guns as having “...a high-gloss polished blued surface, milled triggers, a finely matted sight ramp, a

vertical slot for a lanyard loop machined into the heel of the grip, and grip plates made of selected walnut.” The “sight ramp” mentioned is the semi-circular channel on top of the slide. The Mauser

logo is acid etched on the left front of the slide, as is the slide inscription in upper and lower case sans-serif characters. Many early guns have a reddish stain on the wood of the grips.

The serial number is stamped on the front grip strap. The last three digits of the serial number are

stamped on the bottom of the barrel. The last three digits of the serial number are also usually found inscribed by hand on the bottom of the horizontal crosspiece at the nose of the slide.

About half of the low grip screw HSc pistols went to the Kriegsmarine (Navy) and are so marked. Most of the rest were commercial models. Thus far, only a single low grip screw model is known

to have been purchased by the army. However, the army started buying in quantity just as the high grip screw version began production.

After less than 9000 guns had been produced the firing pin was redesigned.

Most grips in this period are of checkered walnut, but a few black plastic grips are found even on

early guns. The base of the magazine is stamped with the Mauser logo and has a slot on one side where the bottom of the spring locks it in place. Optional finger extension baseplates are also found.

Transitional Production

Mauser soon began seeking ways to increase efficiency and speed production. Pistols produced in

the short period of time between August and November of 1942 show mixed characteristics. Some were like the early production guns described above, and some were like the peak war production

guns described below. We must leave it to the reader to determine the exact characteristics of his gun from this period.

Burnham and Theodore, on page 33 of their book, show photographs of an experimental HSc with a slide stamped from sheet metal, made sometime in late 1942. This technology was not fully

utilized until production of the Heckler & Koch Model 4 in 1968.

Peak War Production

During this period, from November 1942 through August 1943, in order to speed production, polishing time for the slide and frame of the HSc was reduced, resulting in a rougher finish, referred

to by Jan Still as “military blue.” In a private correspondence, Alan Burnham indicates that the bluing time for peak war HSc pistols may have been reduced, as he has noticed considerably more

wear on the grip straps of pistols from this period. The fine matte finish in the sight channel was eliminated, as was the lanyard at the base of the grip. On the interior of the frame, early pistols had

the triangular area in front of the trigger guard milled out to save weight, but this procedure was eliminated in peak war production guns as well, as it required too much time. The magazine

baseplate is flat, with no markings.

Late War Production

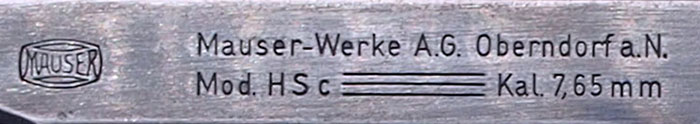

Late war HSc pistols have the slide inscription roll-stamped instead of acid etched, and three horizontal lines were added to the second line between the words Mod. HSc and Kal. 7,65 mm. The Mauser logo was simplified.

Walther had filed suit against Mauser in 1942 for patent infringement. Apparently the suit was not

over design, but functionality, as the parts on the Mauser HSc are not even remotely the same as on

the Walther PP. Walther claimed to have patented the functionality of causing the hammer to fall when the slide is closed with the safety on. As a result of losing the suit Mauser was obliged to

redesign their sear to eliminate this functionality in the HSc. The change took place in September of 1943 at approximately serial number 860000. Near the same time, extra machining steps required

to taper the sides of the magazine release were eliminated.

Later still, the trigger, trigger bar, combination magazine safety/ejector/slide lock lever, and the magazine follower were stamped from sheet

metal instead of being milled. The magazine baseplate has no logo, but is stamped with a half-moon depression at the front. A matte greenish phosphate finish was used instead of bluing.

Black plastic grips are more commonly found in late production pistols.

Presentation Pistols

During the peak war and late war periods Mauser made small numbers of presentation grade pistols with a highly polished deep blue finish, checkered walnut grips, and finger-extension

magazines, often housed in lined leather-covered presentation cases. These rare guns are valuable collector items today. Pender, in his book Mauser Pocket Pistols, refers to these guns as “Swiss,”

without providing a rationale for this designation.

Post War French Production

According to Weaver, Speed, and Schmid, in their book Mauser Pistolen: “Mauser-Werke AG,

Oberndorf was targeted and bombed by the Allies on February 22, 1945. Physical damage to the facility was considered light, but the attack did serve to cripple the firm’s power plant...”

Burnham and Theodore state: “...in May, just one month after the

occupation of Oberndorf, operations resumed at Mauser-Werke under French supervision, primarily to supply their own troops in Indochina.” Burnham and Theodore state: “...in May, just one month after the

occupation of Oberndorf, operations resumed at Mauser-Werke under French supervision, primarily to supply their own troops in Indochina.”

The French restarted the manufacture of of parts, but also made use of an extensive inventory of spare parts to assemble HSc pistols. Swivel or

fixed lanyards were attached to many of these guns. Most French production guns are stamped on the left trigger guard, where it meets the

frame, with a stylized WR monogram that had been previously used by Mauser as a factory proof.

Anecdotal evidence from a French worker at the Mauser plant indicates that two styles of gun were produced by the French. Blued guns were made for use by French police, while guns made

for military use were given a phosphate finish. The French phosphate finish is more of a grey color, rather than the greenish color of German production.

|

Field Stripping the HSc

Make certain there is no cartridge in the chamber and the magazine is empty. Make certain there is no cartridge in the chamber and the magazine is empty.- Cock the hammer and put the safety on.

- Remove the magazine.

- Press down on the barrel release in the front of the trigger guard.

- Press the slide slightly forward and lift it off the frame.

- Use the tip of the magazine base to press the barrel forward and lift it and the recoil spring out of the slide.

|

|

|

Part I: The Mauser Model 1910

Part II: The Mauser Model 1914

Part III: The Mauser WTP

|

|

|

References

- Baudino, Mauro; van Vlimmeren, Gerben. Paul Mauser: His Life, Company, and Handgun Development, 1838-1914. Brad Simpson Publishing, Galesburg, Illinois: 2017. www.paul-mauser-archive.com/

- Belford, James N.; Dunlap, Jack. The Mauser Self-Loading Pistol. Borden Publishing Company, California: 1969.

- Bruce, Gordon. The Evolution of Military Automatic Pistols: Self-Loading Pistol Designs of Two World Wars and the Men Who Invented Them. Mobray Publishing, Woonsocket, Rhode Island: 2012.

- Burnham, Alan D. and Theodore, Peter H. The Mauser HSc Pistol. Privately Printed: 2015.

- Clark, James. “Last of the Magnificent Mausers.” Guns & Ammo, March 1965.

- Ezell, Edward C. Handguns of the World. Barnes & Noble, New York: 1981.

- Görtz, Joachim and Sturgess, Geoffrey. The Borchardt & Luger Automatic Pistols: A Technical History for Collectors from C93 to P. 08. Brad Simpson Publishing, Galesburg, Illinois: 2010 and 2011.

- Hoffschmidt, E.J. “Mauser W.T.P. Old Model,” and “Mauser Pocket Pistol 1910,” and “Mauser HSc Pocket Pistol.” NRA Illustrated Firearms Assembly Handbook. 1952-1960.

- Hogg, Ian V. German Handguns. Greenhill Books, London: 2001.

- Hogg, Ian V. and Walter, John. Pistols of the World. Krause Publications, Iola, Wisconsin: 2004.

- Kinard, Jeff. Weapons and Warfare: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, California: 2003.

- König, Klaus-Peter and Hugo, Martin. Taschen Pistolen. Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart: 1985.

- LaCroix, John. Report to Mauser 1910 Pattern (6.35mm & 7.65mm) Pistol Collectors. Dated 04-03-99.

- Matthews, J. Howard. Firearms Identification. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield Illinois: 1962.

- Maus, L. Donald. History Writ in Steel: German Police Markings 1900-1936. Brad Simpson Publishing, Galesburg, Illinois: 2009.

- Olson, John, Ed. The Famous Automatic Pistols of Europe. Jolex, Paramus, New Jersey: 1976.

- Pender, Roy G. Mauser Pocket Pistols: 1910-1946. Collector’s Press, Houston, Texas: 1971.

- Schroeder, Joseph J. Arms of the World--1911: The Fabulous ALFA Catalogue of Arms and the Outdoors. Follett Publishing Company: Chicago: 1972.

- Schroeder, Joseph J. “The Mauser Model 1906/08 Pistol: Failure or Forerunner?” Gun Collector’s Digest, 5th

Edition. DBI Books, Northbrook, Illinois: 1989.

- Smith, W.H.B. Mauser Rifles and Pistols. Military Service Publishing Company: 1946.

- Stewart, James B. “Mauser 6.35mm Pistols.” Gun Digest, 1970.

- Still, Jan C. Axis Pistols, Volume II. Walsworth Publishing, Marceline, Missouri: 1986.

- Weaver, Darrin W.; Speed, John; Schmid, Walter. Mauser Pistolen: Development and Production, 1877-1946. Collector Grade

Publications, Cobourg, Ontario: 2008.

- Wilson, R.K. Textbook of Automatic Pistols. Small Arms Technical Publishing Co., Plantersville, South Carolina: 1943.

- Wirnsberger, G. “Gleich und doch ungleich: Mauser Selbstladepistolen Kaliber 6,35”, Deutsches Waffenjournal, October 1989.

Special thanks to Alan Burnham for providing additional information about HSc pistols.

|

|

|

Burnham and Theodore state: “...in May, just one month after the

occupation of Oberndorf, operations resumed at Mauser-Werke under French supervision, primarily to supply their own troops in Indochina.”

Burnham and Theodore state: “...in May, just one month after the

occupation of Oberndorf, operations resumed at Mauser-Werke under French supervision, primarily to supply their own troops in Indochina.”