|

19 June 2000. We rose at 5:30. It had stormed during the night and the earth

relished its first moisture in many months. It was cool enough that we could see our breath in the air. I had packed for hot weather but had purchased an

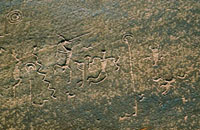

oversized sweatshirt along the way, for which I was very grateful that morning. The climb to the top of El Morro was strenuous, but didn't take long. The view was magnificent. You could see other cuestas scattered upon a dry

rangeland that reached to the horizon. Far below, the first semi's on the highway looked like ants. We came upon the pueblo ruins not long after

reaching the top. The ruins of A'ts'ina Pueblo aren't as large or impressive as 19 June 2000. We rose at 5:30. It had stormed during the night and the earth

relished its first moisture in many months. It was cool enough that we could see our breath in the air. I had packed for hot weather but had purchased an

oversized sweatshirt along the way, for which I was very grateful that morning. The climb to the top of El Morro was strenuous, but didn't take long. The view was magnificent. You could see other cuestas scattered upon a dry

rangeland that reached to the horizon. Far below, the first semi's on the highway looked like ants. We came upon the pueblo ruins not long after

reaching the top. The ruins of A'ts'ina Pueblo aren't as large or impressive as  those at Chaco Canyon or Mesa Verde, but they have only been partially excavated thus far. For A'ts'ina to have been built where and when it was is

remarkable enough. A'ts'ina was occupied for perhaps 30 to 50 years in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. The Ancestral Pueblo (Anasazi) people moved

often, probably because they rapidly exhausted soil and local resources. The pueblo measures about 200 by 300 feet (approximately 60 by 90 meters), and

was probably three stories high in places. It had more than 500 rooms, arranged around a central courtyard. It contains an unusual square kiva. There were no

exterior entrances--access was from above by climbing ladders. We presume this was for defensive purposes. A pueblo across El Morro Valley from A'ts'ina had a nearly-identical floor plan and

was probably built at the same time. those at Chaco Canyon or Mesa Verde, but they have only been partially excavated thus far. For A'ts'ina to have been built where and when it was is

remarkable enough. A'ts'ina was occupied for perhaps 30 to 50 years in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. The Ancestral Pueblo (Anasazi) people moved

often, probably because they rapidly exhausted soil and local resources. The pueblo measures about 200 by 300 feet (approximately 60 by 90 meters), and

was probably three stories high in places. It had more than 500 rooms, arranged around a central courtyard. It contains an unusual square kiva. There were no

exterior entrances--access was from above by climbing ladders. We presume this was for defensive purposes. A pueblo across El Morro Valley from A'ts'ina had a nearly-identical floor plan and

was probably built at the same time.

The El Morro massif encloses a lovely box canyon with pine trees and lush grass that runs right up through the

middle of the rock. The view from the top is simply gorgeous. Ed found himself wishing for a stereo camera to really capture the sense of depth when

looking into the canyon. Only a few minutes later we encountered a German couple, and the gentleman was photographing with a sophisticated-looking stereo camera. Ed wished he had been able to decipher the brand and talk

with him, but only his wife spoke English and we no German. It was so beautiful on top--we could see why the Pueblo Ancestors wanted to live there. The El Morro massif encloses a lovely box canyon with pine trees and lush grass that runs right up through the

middle of the rock. The view from the top is simply gorgeous. Ed found himself wishing for a stereo camera to really capture the sense of depth when

looking into the canyon. Only a few minutes later we encountered a German couple, and the gentleman was photographing with a sophisticated-looking stereo camera. Ed wished he had been able to decipher the brand and talk

with him, but only his wife spoke English and we no German. It was so beautiful on top--we could see why the Pueblo Ancestors wanted to live there.

The next day we set off for

Zuni Pueblo, but most everything was closed when we got there because of fasting for up-coming religious observances and dances. We stopped at a Zuni jewelry and artifact shop where Sybil bought

a Zuni fetish necklace and some earrings. They had some beautiful work and very reasonable prices.

As we crossed into Arizona we entered the Navajo Nation, where we were destined

to spend much of our time on this trip. The landscape changed almost immediately and became very desolate, hot, dry desert. We drove U.S. Highway 191 north, to Chinle and Canyon de Chelly

. From the highway Chinle is an unattractive town, and we simply drove through it on into Canyon de Chelly National Monument. The Canyon de

Chelly campground has been planted with cottonwood trees, whose shade is a blessed relief from the sun. The summers are very hot and dry in this area, most moisture coming

in the form of winter snow. However, it is said that there is always water just a few feet underground down in the canyon. There are no camping fees at Canyon de

Chelly--camping is free. A powerful wind was blowing when we arrived, which made setting up the tent difficult. It got worse before it got better, bowing one side of the tent

almost to the ground, but the fiberglass poles of our Kelty Campsite 4 tent held, a tribute to good engineering and superior construction. The wind finally died down and the heat dissipated sometime in the

night--the evening air was cool and comfortable. Later, our guide told us that such a strong wind is not the norm in the park. As we crossed into Arizona we entered the Navajo Nation, where we were destined

to spend much of our time on this trip. The landscape changed almost immediately and became very desolate, hot, dry desert. We drove U.S. Highway 191 north, to Chinle and Canyon de Chelly

. From the highway Chinle is an unattractive town, and we simply drove through it on into Canyon de Chelly National Monument. The Canyon de

Chelly campground has been planted with cottonwood trees, whose shade is a blessed relief from the sun. The summers are very hot and dry in this area, most moisture coming

in the form of winter snow. However, it is said that there is always water just a few feet underground down in the canyon. There are no camping fees at Canyon de

Chelly--camping is free. A powerful wind was blowing when we arrived, which made setting up the tent difficult. It got worse before it got better, bowing one side of the tent

almost to the ground, but the fiberglass poles of our Kelty Campsite 4 tent held, a tribute to good engineering and superior construction. The wind finally died down and the heat dissipated sometime in the

night--the evening air was cool and comfortable. Later, our guide told us that such a strong wind is not the norm in the park.

20 June 2000. The feature event of the day was our guided hike through Canyon de

Chelly. We had hoped to go on the free tour guided by a park ranger, but they limit the size to15 people and all the slots were taken. So we signed up for one of the tours guided

by a native Navajo, which cost $15. There are three tours daily, in the morning, afternoon, and evening. Our guide was Bobby VanWinkle, who said his last name came from a

Dutchman that married into the family. "It's a long story" was all the explanation he gave. 20 June 2000. The feature event of the day was our guided hike through Canyon de

Chelly. We had hoped to go on the free tour guided by a park ranger, but they limit the size to15 people and all the slots were taken. So we signed up for one of the tours guided

by a native Navajo, which cost $15. There are three tours daily, in the morning, afternoon, and evening. Our guide was Bobby VanWinkle, who said his last name came from a

Dutchman that married into the family. "It's a long story" was all the explanation he gave.

We learned from Bobby that there is some controversy about park rangers giving tours

in the canyon. Canyon de Chelly and its sister Canyon del Muerto are wholly owned by the Navajo Nation, but they asked the National Park Service to come in and manage the

many Pueblo Ancestor (or Anasazi) sites. The Navajo are not supposed to enter the ruins without permission from the Park Service, but on the other hand only native Navajo are

allowed in the canyons alone without a permit. The single exception is the White House ruin, the most famous ruin in Canyon de Chelly. There is a marked trail from which visitors are not allowed to

diverge. The Park Service thinks it should be able to offer free tours to the White House ruin, but from the Navajo

point of view the practice is taking money out of their pockets. Bobby pointed out that the "park ranger" leading the tour was a young volunteer who had only been in the park for two weeks. He said the Park Service really just

needed something for her to do, and that she couldn't possibly know as much about the canyon as someone who,

like him, had been born there and had lived there all his life. While the free tour was full, Bobby only had three people in his tour.

From the canyon rim you can see small fields of corn, beans, and squash

planted by the summer residents of the canyon. All the homes in the canyon are the traditional Navajo hogans, though some have modern roofs. While we were in

Canyon de Chelly, Bobby showed us the location of a home where a Sioux man lived with his Navajo wife. Bobby said that the Sioux man has to have a special

permit to live in the canyon, and it has to be renewed every year. He said the Sioux likes the canyon so much he sometimes stays there all year round. The Navajo generally live in the canyon only in the Summer. From the canyon rim you can see small fields of corn, beans, and squash

planted by the summer residents of the canyon. All the homes in the canyon are the traditional Navajo hogans, though some have modern roofs. While we were in

Canyon de Chelly, Bobby showed us the location of a home where a Sioux man lived with his Navajo wife. Bobby said that the Sioux man has to have a special

permit to live in the canyon, and it has to be renewed every year. He said the Sioux likes the canyon so much he sometimes stays there all year round. The Navajo generally live in the canyon only in the Summer.

The trail from the top went through two tunnels on the way down. Toe-holds chiseled in the rock had been used by Hopi and Navajo residents and possibly also by the Anasazi. The views on the way down are spectacular, but

often difficult to photograph effectively in black and white. However, the White House ruin (so called because one of the buildings was originally plastered in white) is very photogenic, despite being fenced off.

Bobby would stop regularly to tell us stories about the canyon, reminisce about

his childhood, and relate the history of the Navajo Nation. He spoke of the Long Walk, which his great-grandfather and great-grandmother both survived. (I will

intervene here with a little background history, gleaned partly from the web, partly from Bobby, and partly from a book that Sybil has on her shelf entitled American Indians of the Southwest, by Bertha P. Dutton.) From 1864 to 1866 General

James Carleton tried to make the Navajo into farmers, like the Pueblo, but the experiment was a miserable failure. In 1863 Kit Carson, under orders from

Carleton, destroyed all crops and food stores at Canyon de Chelly and Canyon del Muerto, killed all livestock, poisoned wells, and burned hogans. The Navajo hid in the recesses of the canyons, so when winter arrived Carson

blockaded the canyon entrances and shot anyone going in or out. The Navajo were starving, and eventually most of them surrendered. They were marched 350 miles to Fort Sumner (also known as Bosque Redondo) during the

spring blizzards of 1864. The army provided them with standard issue rations, but Bobby said they didn't know how

to eat them and were often unable to digest them. Many died of exposure and starvation on the Long Walk. When

they got to Fort Sumner they were forced to plant crops, which grew poorly but gave them at least some familiar

food to eat. They learned to make fry bread from wheat flour and lard. Within months they contracted smallpox and syphilis from the soldiers and began to die by the hundreds. Bobby would stop regularly to tell us stories about the canyon, reminisce about

his childhood, and relate the history of the Navajo Nation. He spoke of the Long Walk, which his great-grandfather and great-grandmother both survived. (I will

intervene here with a little background history, gleaned partly from the web, partly from Bobby, and partly from a book that Sybil has on her shelf entitled American Indians of the Southwest, by Bertha P. Dutton.) From 1864 to 1866 General

James Carleton tried to make the Navajo into farmers, like the Pueblo, but the experiment was a miserable failure. In 1863 Kit Carson, under orders from

Carleton, destroyed all crops and food stores at Canyon de Chelly and Canyon del Muerto, killed all livestock, poisoned wells, and burned hogans. The Navajo hid in the recesses of the canyons, so when winter arrived Carson

blockaded the canyon entrances and shot anyone going in or out. The Navajo were starving, and eventually most of them surrendered. They were marched 350 miles to Fort Sumner (also known as Bosque Redondo) during the

spring blizzards of 1864. The army provided them with standard issue rations, but Bobby said they didn't know how

to eat them and were often unable to digest them. Many died of exposure and starvation on the Long Walk. When

they got to Fort Sumner they were forced to plant crops, which grew poorly but gave them at least some familiar

food to eat. They learned to make fry bread from wheat flour and lard. Within months they contracted smallpox and syphilis from the soldiers and began to die by the hundreds.

|