|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Smith & Wesson by Ed Buffaloe

Before anyone else, Daniel B. Wesson realized the potential of the Rollin White patent for bored through revolver cylinders, which had been rejected by Sam Colt. Wesson and his partner Horace Smith secured the rights to the patent on 17 November 1856. In August of 1856 Daniel Wesson built a wooden model of a pocket revolver that was intended to shoot a rimfire cartridge which he had invented around 1854 and known today as the .22 short. His first metallic rimfire cartridges were laboriously hand made, but he and Horace Smith eventually built a machine to make them efficiently.

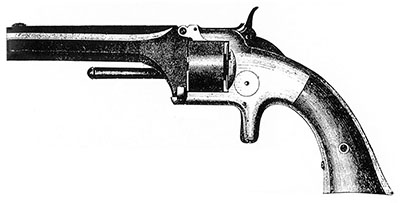

A metal model of the new revolver design was completed in January of 1857. It was a seven shot pocket revolver with the barrel hinged at the top and a latch at the bottom. With the barrel unlatched and swung open, the cylinder could be removed and cartridge cases ejected using the rod beneath the barrel. The perfectionist partners spent most of 1857 refining the design and setting up production facilities, so that, according to Roy Jinks, they only made four revolvers in the first year. The majority of production of what became known as the Model 1 took place in 1858 and 1859 but the design continued to be sold, with three major variants, until 1882. (Historical background is largely derived from History of Smith & Wesson by Roy G. Jinks and Smith & Wesson Hand Guns by McHenry and Roper.)

McHenry & Roper comment: “[In 1902] Daniel B. Wesson, the old inventor and designer of arms, may have felt that his work was drawing to a close and harked back to the first model revolver with which his firm had achieved success. When he had finished his drawings and translated them into metal, he had in his hands the first Smith & Wesson .22 caliber multiple shot arm that had been made in 23 years.”

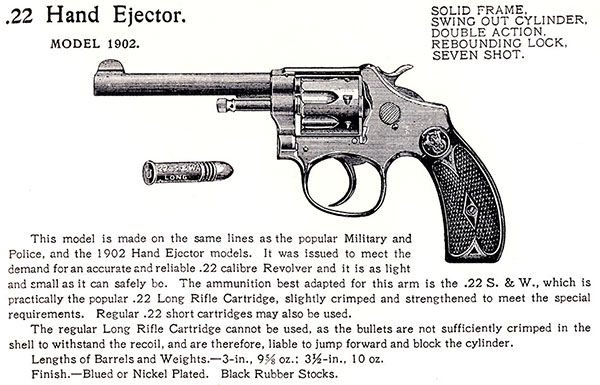

Apparently, Daniel Wesson could not imagine a large .22 caliber revolver and so he made a miniature version of his Hand Ejector which, by today’s standards, is positively tiny, barely filling the palm of a man’s hand. Clearly, it was intended to be a small pocket gun, offered only with a 3 or 3½ inch barrel. The factory designation for the new frame size was “M” and the gun is sometimes referred to as the Model M, though it is always listed in catalogs as the “.22 Hand Ejector”. It quickly picked up the name “Ladysmith” because it was a near perfect fit for a woman’s small hand.

Like its .22 caliber predecessor, the Hand Ejector is a seven shot, but the new gun is chambered for the .22 S&W Long cartridge. Daniel Wesson had originally intended to specify the .22 Long Rifle cartridge for the Hand Ejector but, due to the gun’s light weight, he found that bullets in the uncrimped black powder cartridges of the day would “jump forward and block the cylinder” when the gun recoiled. So Wesson designed a special cartridge for the gun which he called the .22 Smith & Wesson Long. The cartridge had the same 40 grain bullet as the .22 Long Rifle and, according to McHenry & Roper, the new cartridge “differed from the .22 long rifle only in that it was slightly crimped.” Design of the .22 Hand Ejector

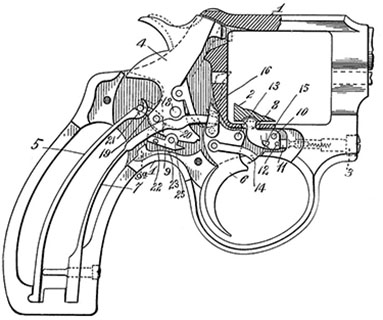

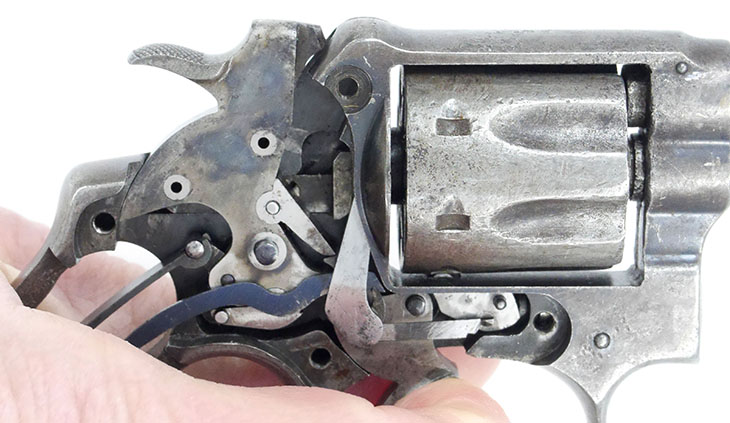

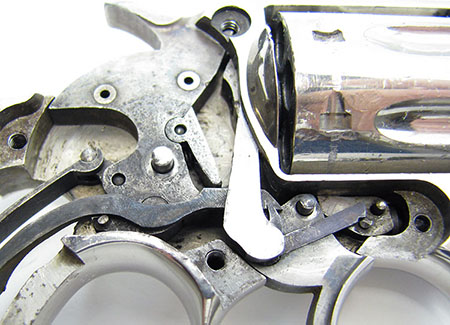

There are two large flat springs mounted in the grip frame. The rear spring, or mainspring, operates the hammer and the forward spring operates the trigger and the rebound mechanism. A seesaw lever pivots on a pin fixed in the base of the hammer and is referred to by Smith & Wesson as the “rebound catch”. With the trigger at rest, the rebound catch acts to prevent the hammer from reaching the cartridge primer; the trigger spring presses down on the rebound catch, holding the hammer back, out of reach of the cartridge.

If the hammer is pressed forward without the trigger being pulled, the rebound catch locks against the frame, preventing further movement of the hammer. There is a small spring and plunger in the foot of the hammer that forces the front end of the rebound catch down and the rear end up, when the trigger is pulled. Pulling the trigger causes the trigger spring to be lifted upward by the hand, allowing the rebound catch to clear the frame.

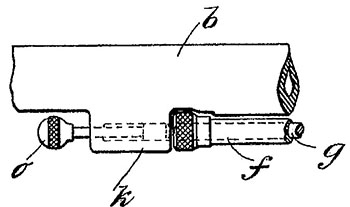

The cylinder stop sits in the front of the lockwork recess inside the frame. Its purpose is to lock the cylinder in firing position. The stop turns on a separate pin which is fitted through the stop and into the frame. The stop is activated by a lever on the trigger which engages a protrusion on the side of the stop. The patent shows the stop spring held by a screw in front of the frame but, in practice, this is where the yoke attaches to the frame, so a spring activated plunger is fitted to the end of the yoke pivot to tension the cylinder stop.

The cylinder stop engages the cylinder notches through a slot in the bottom of the frame. When the trigger is pulled, the front trigger lever pulls the stop down and out of engagement with the notch in the cylinder, while at the same time a pawl (the “hand”) attached to the rear of the trigger, rotates the cylinder in a counterclockwise direction. The rear nose of the trigger engages the double action sear, rotating the hammer backward. When the trigger gets to the end of its pull the nose slips off the sear and releases the hammer. The single-action sear is the small ledge beneath the toe of the hammer. This ledge catches on the rear trigger lever when the hammer is manually cocked. The hand is tensioned by the trigger spring. The trigger spring presses downward on the rear of the hand but the hand needs to be tensioned in a more forward direction, so a tiny rotating lever is fitted to the back of the hand. This lever engages with a notch near the end of the trigger spring, leveraging the hand forward. The cylinder locks only at the rear. The cylinder release button, unlike any other Hand Ejector before or since, is pulled to the rear to allow the cylinder to be swung out. The cylinder release does not lock the hammer when the cylinder is open, nor does it prevent the cylinder from being opened when the hammer is cocked. The cylinder yoke is pinned in place; it is not retained by a screw like other Hand Ejector revolvers.

Marks and Inscriptions The earliest .22 Hand Ejector I have documented (serial number 215) has no barrel inscription of any kind. Most guns, however, are stamped on the left side of the barrel in upper case sans serif characters: 22 S. & W. CTG The inscription stamped on top of the barrel reads: SMITH&WESSON SPRINGFIELD MASS. U.S.A. The patents referenced above are:

The gun is finished in either blue or nickel plate. The Smith & Wesson trademark monogram is stamped on the left side of the frame beneath the cylinder release button.

Stocks are of checked hard rubber with the Smith & Wesson monogram in a circle at the top. Examples are often seen with mother of pearl stocks; if from the factory, they should have the serial number scratched or penciled on back of the right stock. The serial number is also stamped on the base of the grip frame, the back of the cylinder, on the barrel flat, on back of the ejector star, and back of the right stock. McHenry & Roper comment: “The combination [of gun and cartridge] worked perfectly, but the model did not have a wide sale.” After more than four years, only 4575 had been made. Daniel B. Wesson died on 4 August 1906, the same year in which the .22 Hand Ejector was redesigned, but the timing is likely coincidental. I believe he had been planning an update for some time because he filed a patent for the front-pull cylinder lock and release in March of 1903.

Not a lot is changed. The Second Model .22 Hand Ejector sees the elimination of the cylinder release button which is replaced with a pull release at the front that serves to lock the cylinder pin. A barrel underlug is added to support the new pull release, bringing the design more in line with the larger caliber Hand Ejectors. The gun continues to be sold as the “.22 Hand Ejector, Model 1902”. The quality of workmanship, of course, remains first rate.

Roy Jinks, in his History of Smith & Wesson, says of the First Model .22 Hand Ejector: “This tiny pistol...proved to be a challenge to the factory. The parts were extremely small and difficult for the men at Smith & Wesson to assemble.” He specifically cites the cylinder release button and lockwork as difficult to assemble and as the reason for the redesign of the gun, but the only small parts eliminated were the cylinder bolt, its spring, and its button—the rest of the tiny lockwork remains unchanged. While I am sure there were complaints about the small parts, I personally believe the redesign had more to do with providing a positive lock for the front of the cylinder pin to keep the cylinder in proper alignment with the barrel.

The 1909 Smith & Wesson catalog listing for the Second Model shows that it continued to be offered in 3 inch and 3½ inch barrel lengths. Neal & Jinks note: “One of this model (12,876) is known with 6” barrel and target sights; therefore, a few others may have also been made.” Likewise, I have identified at least one gun (13,531) with a 2¼ inch barrel and the inscription stamped on the right side of the barrel. There may be others. All external markings and inscriptions remain the same as the First Model. A total of 9,374 of the Second Model were made.

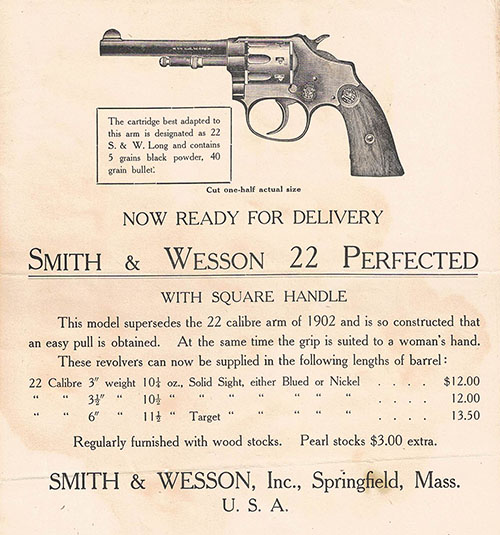

In 1911, the .22 Hand Ejector was internally updated with the latest Smith & Wesson lockwork innovations, and the frame was given a square grip. Roy Jinks, in his History of Smith & Wesson, notes: “The 1910 circular announced this model as the .22 Hand Ejector Perfected Model...and stated that the revolver was available in 2¼”, 3”, and 6” barrel lengths, with the latter length being available with target sights.

A copy of a similar circular was found folded into a 1909 Smith & Wesson catalog, though I do not know if it actually came with the 1909 catalog or was added later. It refers to the gun as the “22 Perfected” and states that it will be available in 3, 3½, and 6 inch barrel lengths. I have documented Third Model .22 Hand Ejectors with 2¼ inch, 3 inch, 3½ inch, and 6 inch barrels. Jinks gives 1909 as the date for the origin of the “.22 Hand Ejector Third Model”. McHenry & Roper give May 1911 as the first date of manufacture. The gun first appears in the 1911 catalog. It is quite possible, if not likely, that the gun was in the planning stages as early as 1909. The .22 Perfected was never actually called the “Third Model” by Smith & Wesson in their catalogs and price lists; the gun was always referred to as the “.22 Hand Ejector”. “Third Model” seems to be a terminology established and used primarily by collectors, including myself.

The .22 Perfected represents the introduction of the first fully modern lockwork for a .22 Hand Ejector. The lockwork design was indeed perfected in the larger caliber Hand Ejectors between 1906 and 1909, and includes Joseph Wesson’s patented rebound slide (U.S. Patent № 811807) and Charles M. Stone’s patented trigger and hammer modifications (U.S. Patent № 933797), giving the Smith & Wesson revolver the smoothest double action trigger pull in the world, in its day.

The rebound slide takes the place of the rebound lever in the earlier .22 Hand Ejector revolvers. The evolution of Smith & Wesson lockwork is covered in some detail in my article on the .32 Hand Ejector; I see no need to review it here. The .22 Perfected lockwork is a miniature version of the .32 Hand Ejector Model 1903 Fifth Change which appeared in 1910. The only thing it lacks is the cylinder release bolt and thumbpiece. As on other Hand Ejector revolvers, the cylinder yoke is retained by the front sideplate screw, instead of the pin of the earlier models. The .22 Perfected is a “five-screw” model, with four screws in the sideplate and one to hold the spring and plunger for the cylinder stop. The six inch barrels all have a pinned front sight, even if the rear sight is not adjustable.

Marks and Inscriptions The .22 Perfected revolver is stamped on the left side of the barrel in upper case sans serif characters: 22 S. & W. CTG The 2¼ inch barrels I have documented retain the barrel inscription of the earlier versions of the gun. Stamped on the right side of the barrel (because there isn’t room on the top) is: SMITH&WESSON SPRINGFIELD MASS. U.S.A. The reason the earlier roll stamp was used for the short barrel is probably that the later inscription was too long to fit, even on the side of the barrel. An alternative reason might be that the barrels were made and stamped for the Second Model and were later used on the Third Model. The inscription stamped on top of three inch and longer barrels reads: SMITH&WESSON SPRINGFIELD MASS. U.S.A. The patents referenced above are:

The Smith & Wesson trademark monogram is stamped on the left side of the frame. The square butt stocks are of plain walnut with a brass Smith & Wesson monogram inset at the top. Factory mother of pearl stocks feature a gold plated brass S&W monogram.

Evaluation Roy Jinks comments: “The barrel length expansion was done to increase the sales of this small revolver but this proved unsuccessful. The Third Model sold only 12,203 revolvers.... [It] was difficult to manufacture and required frequent repairs, either because of the delicate small parts or the fact that the owners used a .22 Long Rifle cartridge instead of the .22 S&W Long.” Smith & Wesson made an effort to sell the .22 Perfected as a target pistol, but as McHenry & Roper state: “Its square butt was still too small to afford the average hand a steady grip.” The gun was never widely adopted by target shooting enthusiasts. In June of 1911, Smith & Wesson began to make the .22/32 Heavy Frame Target Revolver, using the I frame which, with its larger size and larger stocks, was more readily accepted by target shooters. The .22 Hand Ejector was relegated to the status of a ladies’ gun, or a mere curiosity, but eventually became a favorite of Smith & Wesson collectors.

Why .22 Hand Ejectors are often in poor condition today. Daniel B. Wesson was one of the key men who actually invented metallic cartridges. He had a long acquaintance with black powder and very likely believed, as many of his contemporaries, that it was a better choice for .22 rimfire ammunition because of its slow burning characteristic, giving less recoil and greater accuracy. A.L.A. Himmelwright, in his 1908 book Pistol and Revolver Shooting, says the following: “Until 1907 black powder ammunition was used almost exclusively for pistol and revolver shooting. ... In the .22 caliber pistols, the fouling of the black powder is not a very serious matter, and it is not uncommon to shoot fifty or a hundred rounds without the necessity of cleaning.” Michael Bussard, in The Ammo Encyclopedia, writes: “Most small game hunters quickly preferred smokeless powder loads although match shooters clung to black powder and semi-smokeless powder loads until the early 1930s.” [My italics.] An early brochure announcing the Smith & Wesson .22 Perfected revolver clearly states: “The cartridge best adapted to this arm is designated as 22 S&W Long and contains 5 grains black powder, 40 grain bullet.” The 1909 Smith & Wesson catalog has the same statement. Ergo, the .22 Smith & Wesson was a black powder cartridge. Additionally, non-corrosive priming materials were not developed until the 1920s, so, adding to the corrosive effects of black powder, there was also the corrosive effect of salt residues from the primers of the era. Any gun not cleaned immediately after use would suffer from rapid metal corrosion wherever powder and primer residue collected. We see this corrosion in many of the remaining .22 Hand Ejectors. Heat treating of cylinders did not begin until May of 1919, so none of the parts of the .22 Hand Ejector were heat treated, with the doubtful exception of a few very late Third Model cylinders. The .22 Hand Ejector was never designed for high pressure smokeless powder loads, which is why Smith & Wesson recommended their own brand of low pressure black powder cartridge. The black powder cartridge was quite corrosive but the cleaner smokeless powder cartridges were too powerful for the delicate revolver. Unless the right cartridges were used, and the gun assiduously cleaned and lubricated after every use, rapid deterioration was almost inevitable.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright 2023 by Ed Buffaloe. All rights reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||