|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A .25 ACP Steyr Model 1909 with Long Barrel:

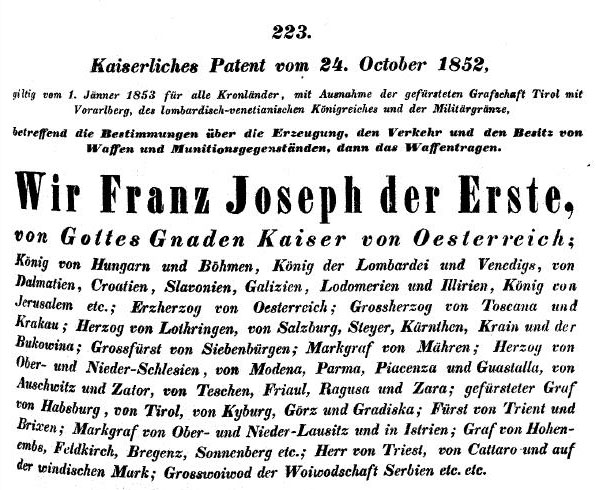

Let me start by giving some information about the Steyr Model 1909. Basically, there are two models – early and late versions. The early ones have a flat and thin barrel release lever whereas later ones have a wider thicker one. Here we have an early version. The condition of the gun is quite good – the bluing is thin but has no rust, and the bore is in excellent condition. These long barrel guns are an Austrian curiosity. But what was the reason for extending the barrel and making a handy vest pocket pistol considerably less handy? There are rumors and misconceptions. For example James Stewart (in “Those Lo-o- ong Barrel .25’s,” Gun Collector’s Digest, 1974) refers to the industrial revolution and the 1906 introduction of the 6.35mm Browning cartridge. He states that the law was to prevent small vest pocket pistols like the Browning from coming into the wrong hands. But in fact the 18 cm limit is much older than most people think. To explain why we must take a look at the Austrian gun legislation of the nineteenth Century. In the year 1906, when production of the Steyr pistol started, Austria was still living with a gun law from 1852 (picture 2). In 1852 the Austro-Hungarian Empire was ruled by Franz Joseph I (see picture 3). We must remember that while Colt was mass- producing his revolvers by 1847 (or earlier), at the same time in Europe the state-of-the-art technology was still single shot black powder pistols.

The Kaiserliches Waffenpatent was created to prevent misuse and to effectively control weapons. It regulated the production, trade, and ownership of weapons and ammunition, as well as the carrying of weapons. It separated legal and illegal weapons. Possession of legal ones was more or less free whereas

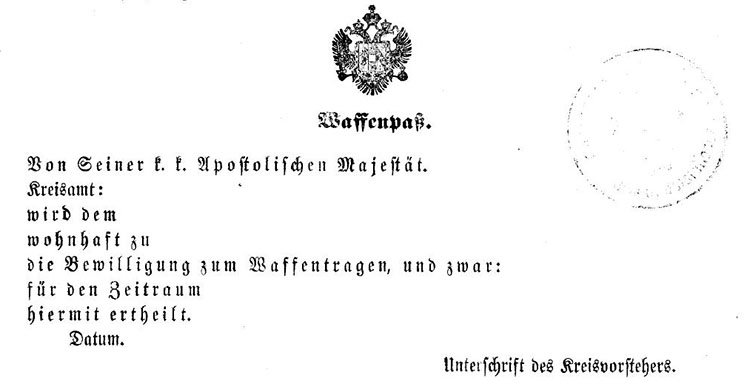

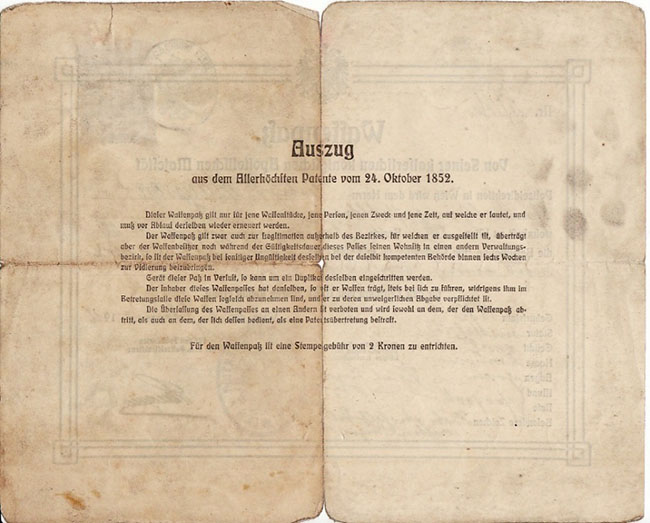

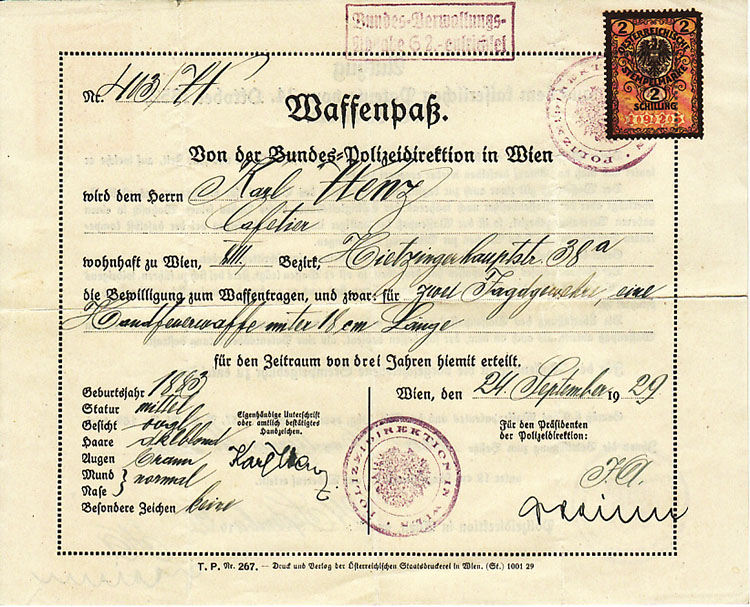

Article 2 defined the different types of restricted or illegal weapons: e.g., daggers, stilletos, muzzle-loading pistols (Terzerole) shorter than 7 “Wiener Zollen” (7 inches), air rifles, handgrenades, rockets, cane guns and all other objects which could he easily hidden and used for perfidious attacks. Here is the original text: Dolche, Stilette und hohlgeschliffene stiletartige Messer, dreischneidige Degen, Trombone, Terzerole unter dem Masse von 7 Wiener Zollen, mit Inbegriff des Schaftes und Laufes, Windbüchsen jeder Art, Hand- und Glasgranaten, Petarden und Brandraketen, endlich alle verborgenen, zu tückischen Anfällen geeignete Waffen, was immer für einer Art, wie z.B. Stockflinten, Degenstöcke u. dgl. […] sowie im Allgemeinen jedes versteckte, zu tückischen Anfällen geeignete Werkzeug. This is the source of the 7 inch rule. So possession of illegal or restricted guns was prohibited unless one had special permission from the federal authorities. All other guns could be freely owned without any permission so long as the number did not exceed a reasonable quantity. The permission to possess illegal weapons did not include the right to carry them. Therefore another special permission was required (Waffenpass). Every inoffensive person had the right to get a Waffenpass. The license was valid for three years or for special purposes. The format of the license was defined in the “Vorschrift wegen Handhabung des Allerhöchsten Patentes vom 24. October 1852 über die Erzeugung, den Verkehr und den Besitz von Waffen und Munitionsgegenständen“ from 29. January 1853 (see picture 4). The front page of the form had all the necessary data and on the back were special instructions.

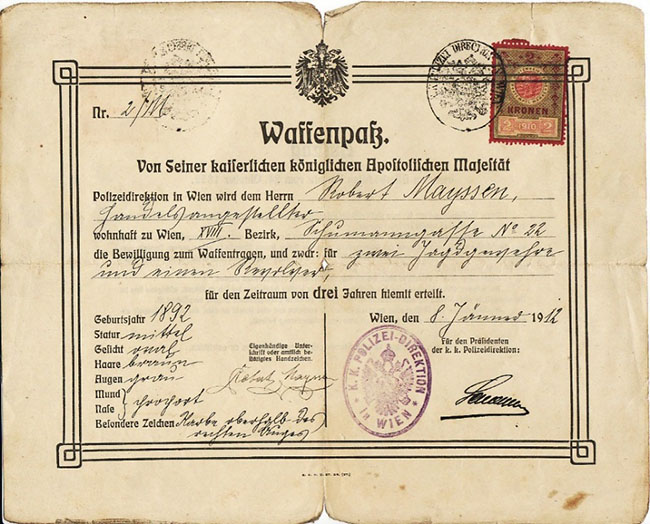

Later it was ordered that the license be amended to include the signature and personal description of the owner in order to prevent misuse. Picture 5 shows such a license.

Gun legislation needed to keep up with technical progress. Single-shot muzzleloader pistols of the 1850’s had nothing in common with modern firearms of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In September 1897 the ministry of interior declared that revolvers were illegal weapons according to article 2 of the Kaiserliches Waffenpatent. But a mere two month later in December 1897 it was ordered that revolvers shorter than 7 inch would no longer fall under that rule. The rationale was simple. The ministry stated that due to the short barrel, resulting bad accuracy, and weak ammunition those revolvers were not comparable with Terzerols (the small muzzleloading pistols of the era) and therefore would not fall under article 2. For our German speaking audience the full text of the act may be of interest: Voraussetzungen für die Behandlungen von Revolvern als verbotene Waffen. […] Das Ministerium des Inneren hat seinerzeit mit Erlass vom 8. September 1897 Z. 8351 über die Frage, ob Revolver zu den verbotenen Waffen gehören, ausgesprochen, dass sie, insoferne sie „mit Inbegriff des Schaftes und Laufes unter dem Masse von 7 Wiener Zollen sind, wie andere Schusswaffen unter diesem Masse nach §2 des Waffenpatentes vom 24. October 1852 zu den verbotenen Waffen gehören.“ Gleichzeitig wurde aber beigefügt: „Insofern sie aber das Mass von wenigstens 7 Wiener Zollen haben, können sie nach der positiven Anordnung des bezogenen Paragraphen zu den Waffen nicht gezählt werden. Denn, wenn sie auch zu tückischen Anfällen geeignet sein mögen – eine Eigenschaft übrigens, die jede Pistole hat [sic!] – so sind sie doch nicht verborgene Waffen und es treten daher bei Ihnen die im §2 bezeichneten Merkmale einer verbotenen Waffe nicht ein.“ Es geht daraus hervor, dass die Revolver keineswegs zu den im Schlussabsatze des §2 Waffenpatentes erwähnten verborgenen und zu tückischen Anfällen geeigneten Waffen gezählt werden, denn die leichte Verbergbarkeit ist nicht identisch mit der Verborgenheit des Waffencharakters (bei Stockflinten, Degenstöcken) und die Eignung zu tückischen Angriffen vermag für sich allein die Erklärung zu einer verbotenen Waffe nicht zu begründen. Es wurde vielmehr die Analogie zu den Terzerolen herangezogen, welche im ersten Theile des §2 Waffenpatentes aufgeführt sind, also unter jenen Waffen, deren erhöhte Gefährlichkeit für die körperliche Sicherheit die Erklärung ihres Verbotes rechtfertigt. Die seither gemachten Erfahrungen der Waffentechnik haben jedoch ergeben, dass die Analogie der Terzerole und Revolver nicht zutrifft. Bei letzterem mindert sich durch die Verkürzung Treffsicherheit und Schusswirkung derart, dass man den kürzeren Revolvern keine erhöhte Gefährlichkeit zusprechen kann, indem die grössere Leichtigkeit der Handhabung durch die geringere Wirkung aufgewogen wird. Das Ministerium des Inneren findet daher im Eivernehmen mit dem Ministerium der Justiz und für Landesvertheidigung der k.k. Landesbehörde zur Danachachtung und entsprechende Belehrung der Unterbehörden zu eröffnen, dass künftighin Revolver unter dem Masse von 7 Wiener Zoll (18 Centimeter, Ministerialverordnung vom 4. December 1875, R.G.Bl. Nr. 148) den Terzerolen glei-cher Länge nicht mehr schlechthin gleichzustellen und daher auch nicht mehr allgemein als verbotene Waffen zu behandeln sind (22. December 1897, Z. 29606). This act was valid for about 15 years, until 1912, when the ministry of interior again changed its policy. On 21 May 1912 it stated that due to ongoing technical developments, in particular modern self-loading pistols, the policy promulgated in the 1897 act was no longer compatible with article 2 of the 1852 act. Some provincial authorities had been treating self-loading pistols as equivalent to revolvers which could be possessed without further license. As a consequence, the ministry of interior ordered that all firearms shorter than 7 inches should fall under article 2. But the ministry was not completely blind and could not ignore the situation created by the new small weapons. They ordered authorities to generously approve all requests concerning production, selling, trade, possession and carrying of weapons. To sum it up: Between 1897 and 1912 revolvers and – according to some provincial authorities – pistols shorter than 7 inches were considered legal firearms that could be possessed by anyone. After 1912 they became illegal again and required a special license. After 1912 we should find vest pocket pistols with barrel extensions for those people who wished to obviate the letter of the law. Licenses of that time show the curious legal situation. Whereas a license from January 1912 does not show the length of the gun, later ones show it again. In 1915 the format of the license was probably altered because the Austro-Hungarian coat of arms was changed. Unfortunately I do not have a post-1915 example. Then with the end of the Austro -Hungarian Empire after WWI the format was changed again. The Emperor’s Double-Eagle disappeared and was replaced by the emblem of the appropriate federal agency (see picture 6).

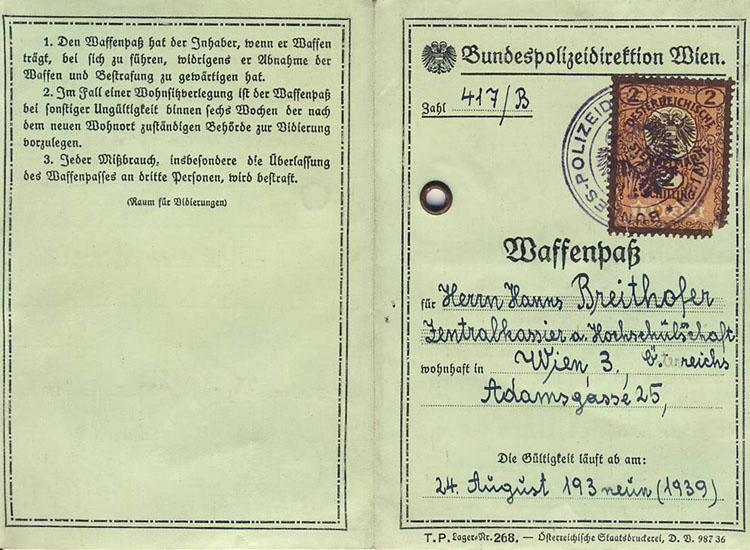

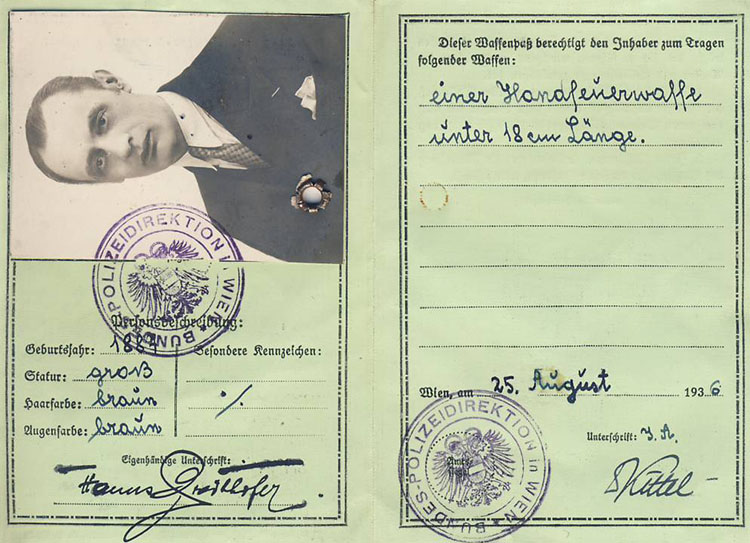

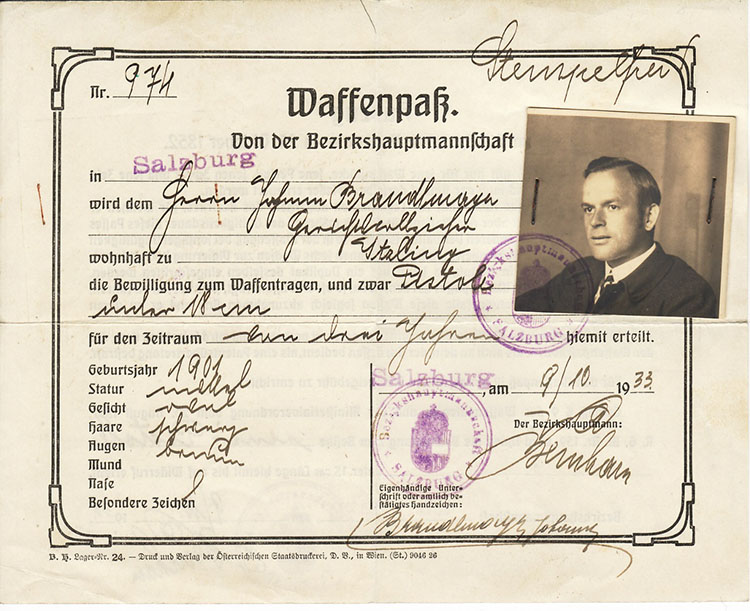

In 1933 the sample of the Waffenpass was completely changed (picture 7). On an interim basis the old forms could be used up if they additionally showed a picture of the owner (picture 8). With Austria’s annexation by the German Reich in 1938 the Waffenpatent was suspended after more than 90 years and German gun laws were introduced on 13. February 1939.

Finally some may think this article contains more information than necessary to solve the secret of my Steyr 1909. Ultimately the long barrel is a result of the legal situation. Due to its length this gun was a legal firearm and did not require a special license to purchase. We discussed guns, laws, and documents. My aim was to show that guns always have a history and must be viewed in light of the technical, social. and legal aspects of their time. The historical context makes gun collecting much more interesting than the purely technical aspect. My special thanks go to Dr. Richard Preuss who provided the various Waffenpass examples and Mr. Ed Buffaloe for editing the article and providing a platform to publish it. Additional Waffenpass Documents

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright 2014 by Dr. Stefan Klein. All rights reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||