|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The High Standard by Ed Buffaloe

The Story of the Crusader Charles Petty, writing in 1984, maintained that: “The story of the Crusader is so intimately connected with the recent history of High Standard that it is impossible to tell of one without the other.” So, a little history: The High Standard company was founded in 1926 and began manufacturing self-loading .22 target pistols in 1927. With hard work and quality products, the company prospered even during the Great Depression. In World War II High Standard became an important part of the war effort, when virtually all its production went to government contracts. Many G.I.s who had never shot a gun before learned to shoot using a High Standard .22 pistol, giving the company a brand recognition that would serve it well after the war. In 1955 High Standard began manufacturing a line of .22 revolvers. They evolved and expanded this line for more than a decade. The business began to decline somewhat after 1963 when Sears discontinued handgun sales, and after the Gun Control Act of 1968 it is believed that High Standard’s business may have been reduced by as much as 60% because most other major retailers also stopped selling handguns at this time.

After the acquisition of High Standard by The Leisure Group, a number of experienced engineering people and shop personnel were eliminated to reduce costs, while at the same time management was directed to expand the product line and try to maintain market share. Petty states: “Dan Wesson and Auto-Mag produced versions of their handguns bearing the High Standard name. The company also offered a line of quality shotguns produced by a Japanese maker [Nikko] and sold as the High Standard Shadow.” These efforts did not require anything of High Standard other than branding and marketing, and the deal was good for both companies, because at the time Dan Wesson was struggling to stay in business, and the orders from High Standard saved the company, at least for for a few years. But High Standard management ultimately decided they needed a product of their own design. At this time, the .44 Magnum was all the rage. In December of 1971 the movie Dirty Harry premiered, starring Clint Eastwood as a cop who carried a Smith & Wesson Model 29 in .44 Magnum, which he touted as “the most powerful handgun in the world.” The Smith & Wesson Model 29 became a very sought-after item, and the company could not make them fast enough. In the 1973 issue of Gun Digest the Model 29 is listed at $194, but in reality they often sold for $400 or more due to high demand. Early in 1973 High Standard hired an engineer by the name of Dick Baker to design a revolver for the .44 Magnum cartridge.

Baker was the primary design engineer, though an engineer by the name of Ralph Kennedy was also assigned to work on the project, and took it over after Baker left to work for Smith & Wesson. The gun Baker designed was highly innovative, with a gear-driven double-action trigger, an advanced cylinder lock mechanism, and a hammer that pivoted on an eccentric in such a way that it could not strike the firing pin unless the trigger was pulled. Kennedy designed a combination cylinder release and safety lever that locked the cylinder, trigger, and hammer. Baker and Kennedy produced their first prototypes, a medium-frame .357 Magnum and a large-frame .44 Magnum in the Fall of 1974. The .44 was originally marked “The Valkyrie,” though it was later renamed “Crusader.” Charles Petty was invited to the High Standard facility in Hamden, Connecticut to test fire one of the early prototypes. He wrote: ... I was able to shoot one of the first prototypes in High Standard’s basement range. It was a rare privilege, for I was one of the first outsiders to get his hands on one. I was impressed with the smooth double action, but my repeated questions about production plans were met with uncertain answers. The heart of the problem and the reason for the many delays was money. The cost of tooling up for production was estimated at at least $1,000,000 and High Standard didn’t have that kind of money to spend. Although there were some proposals for fund raising, none were acceptable to the parent company and, in the spring of 1975, the Crusader project went on hold.

Petty states that Fabrique Nationale (FN) of Belgium had been negotiating to buy High Standard’s riot shotgun when they learned about the Crusader and expressed an interest in buying the .357 version to sell as a police gun in Europe. FN was impressed with the Crusader but apparently thought the price was too high and could not come to terms on a deal. FN eventually bought revolvers made by Llama of Spain and sold them as the Barriduca. I own an FN-branded Barricuda revolver—it is well made but is not even close to the level of accuracy I would expect from a gun with the FN brand. I’m sure Llama made the Barricuda more cheaply than High Standard could have, but I think FN and High Standard both missed an opportunity. By late 1977 The Leisure Group was having financial difficulties. Profit margins were not high enough to service their debt in an economy where the prime rate was 11.75% and the interest on their loans averaged 15%. TLG sold Lyman Gun Sights for two million dollars in November and needed to sell High Standard as well. In January of 1978 High Standard’s management gathered together a small group of investors to buy the company from TLG for a mere $600,000.

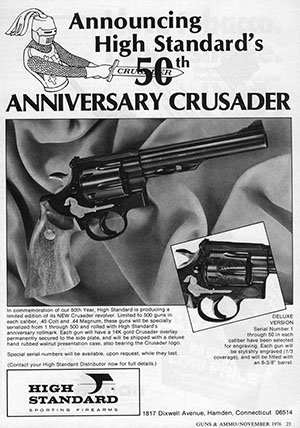

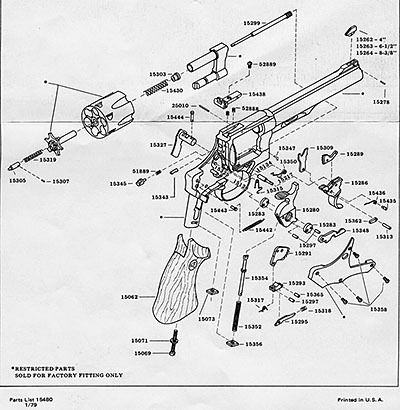

The new owners knew they had to make good on the Crusader, but production would have to be on a limited basis in small batches. The first Crusader was shipped on 10 November 1978, and it was June of 1983 before the last of the guns was completed. No further Crusaders were ever manufactured. According to Jon Miller, one of the preeminent collectors of Crusader revolvers:

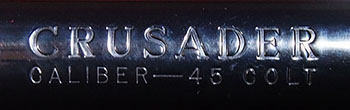

The 1978 and 1979 issues of Guns Illustrated list the High Standard Crusader Commemorative Revolver, but state that the price is unavailable. The 1980 issue lists the gun, available in three barrel lengths, and in .357, .44, and .45 caliber, with a price of $335 for the 4-1/4” barrel, $340 for the 6-1/2” barrel, and $345 for the 8-3/8” barrel. In the same issue the Smith & Wesson Model 29 is listed at $331 with a 6-1/2” barrel, or $342 with an 8-3/8” barrel. In the 1981 issue the Crusader is listed as available only in .44 or 45 caliber and only in the two longer barrel lengths, but the price is again listed as “not available.” In 1983 the Crusader is no longer listed. The early articles on the Crusader had all promised that the new gun would be much cheaper than the Smith & Wesson, but apparently High Standard was unable to produce it as cheaply as projected. At this point the Crusader project had to be abandoned. The gun was too expensive to manufacture and still be competitive. The market for .44 Magnum revolvers was already beginning to decline, and the market for new .45 Colt revolvers was even smaller. So today the Crusader remains a collector item. No one shoots the commemoratives because they are too valuable--a sad end for an innovative and promising design.

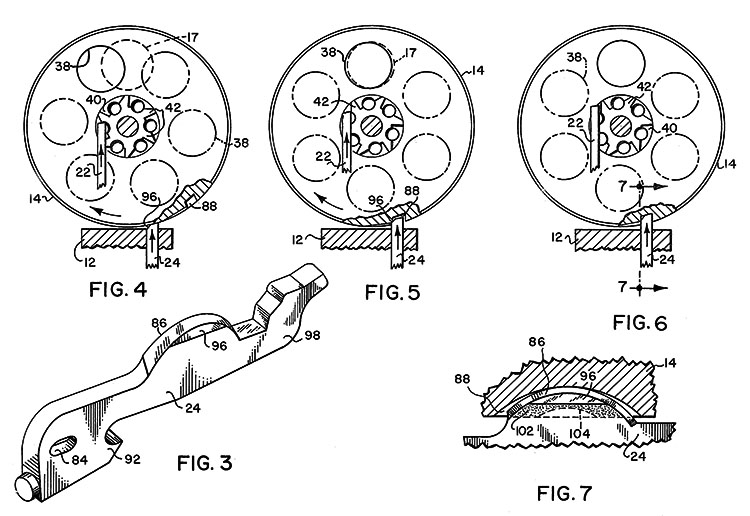

The Patents Both Howard French and George Nonte, in their 1976 articles, state that five patents were filed for various design aspects of the Crusader pistol. However, I have only been able to locate four patents. I will take them in the order in which they were filed. U.S. Patent 4,001,962 This patent, entitled “Cylinder Indexing Means for Revolvers,” was filed by Richard L. Baker on 25 November 1974, and was granted on 11 January 1977. The gist of the patent is the very simple idea of putting a beveled edge on one side of the cylinder lock to help cam the cylinder into position. The patent abstract states it succinctly: “The cylinder lock is provided with a cam -surface on its cylinder-engaging portion that engages the leading edge of the notch for camming the cylinder the rest of the way into its fully indexed position.” The patent drawings give a preview of an already fully evolved new revolver design. The cylinder locking bolt is much larger than that seen on other revolvers.

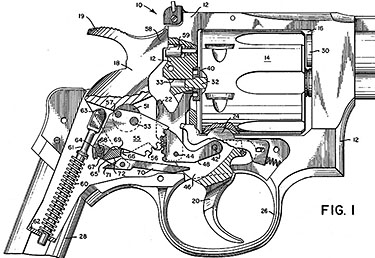

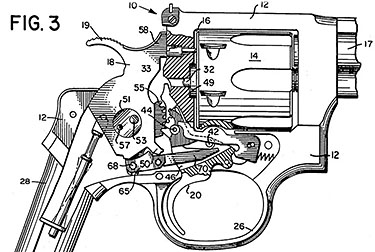

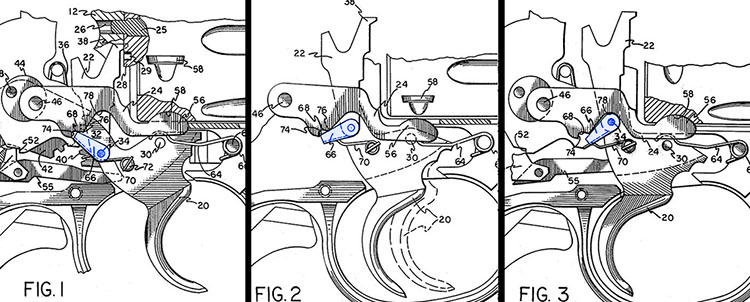

The patent states: “...the cylinder hand 22 does not need to rotate the cylinder completely into registry with each notch 88, but can disengage the cylinder as soon as the leading edge of each of said notches comes into engagement with the cam-surface 96 on the cylinder lock. The upward pressure exerted by lock 24 then causes the cylinder to be rotated the rest of the way until lock 24 is fully engaged within the notch. This sequence is well illustrated in the series of views shown in FIGS. 4-6.” A bushing or engagement lug extends out from the trigger and engages the locking bolt only when the trigger is all the way to the rear, mechanically pressing it upward. The cam surface on the locking bolt cams the cylinder into proper alignment and fixes it in place. The patent states that no matter how slowly the trigger is pulled, this mechanism ensures correct alignment of the cylinder with the barrel for every shot. U.S. Patent 3,996,686 This patent, entitled “Gear-driven Double-action Firing Mechanism for Firearms,” was filed by Richard L. Baker on 24 March 1975, and was granted 14 December 1976. The patent covers both a gear-driven double-action mechanism “to provide an easier and smoother pull during double-action” and a hammer that pivots on an eccentric “in such a way that unless the trigger is pulled, the hammer is out of alignment with the firing pin.” Baker cites earlier patents that utilize similar mechanisms, some from the 19th century.

The eccentric (51) turns on the hammer pin (53). The hammer itself turns on the eccentric. A coil spring is visible at the front of the cylinder lock (unmarked). The bushing or engagement lug (44 in Fig. 3) attached to the trigger mechanically activates the cylinder lock. U.S. Patent 3,988,847 This patent, entitled “Combined Cylinder-Release and Safety Lever for Revolvers,” was filed by Ralph C. Kennedy on 8 September 1975 and was granted on 2 November 1976. From the patent: “. ..an object of the present invention is to provide a cylinder-release lever which can be manipulated not only to release the cylinder, but also to positively lock the trigger mechanism, thereby avoiding the necessity of adding a separate safety lever. Another object of the invention is to prevent inadvertent locking of the trigger mechanism due to accidental movement of the combined cylinder-release and safety lever to its safe position.” The release lever simply depresses the cylinder spindle so that “...the end of the spindle is driven out of its latching passage in the frame, releasing the cylinder so that it can swing outward to one side of the frame.” The patent describes the entire revolver mechanism in detail, referring to the two earlier patent applications, in order to explain how the safety mechanism works. Essentially, when the shaft of the cylinder release mechanism is displaced sideways it locks the cylinder release, preventing the cylinder from being opened, and blocks the movement of the cylinder hand, which of course is tied to the trigger, hence it effectively locks both the trigger and the cylinder. U.S. Patent 4,173,090 This patent, entitled “Cylinder-Locking Device for Revolvers,” was filed by Richard L. Baker on 11 May 1978 and was granted on 6 November 1979. This patent is an elaboration and improvement on the mechanism described in the previous patents, which did not specify the means by which the cylinder lock is unlocked during rotation of the cylinder. This patent describes the mechanism which mechanically unlocks the cylinder. The engagement lug on the trigger (described in patent 4,001,962) which mechanically locks the cylinder bolt has a lever (or actuator) attached to it which mechanically forces the cylinder locking bolt down and out of engagement with the cylinder as the trigger is pulled to the rear. When the cylinder hand has moved the cylinder into position, the actuator is cammed out of engagement with the cylinder locking bolt. The spring that tensions the cylinder bolt forces it upward, and as the trigger moves all the way to the rear the engagement lug on the trigger mechanically holds the bolt in the locked position. The entire mechanism provides mechanical leverage for both the unlocking and locking of the cylinder bolt. The patent notes that “the actuator is also arranged so that the cylinder-lock spring is not compressed during the return stroke of the trigger,” hence providing a faster trigger return.

Design and Evaluation A.W.F. Taylerson, in his 1967 book Revolving Arms states: “Although the revolver is over three hundred years old as a basic design, in fact any major improvement of that design has been a rare event throughout those centuries.” The double-action lock-work mechanisms in use today all have their roots in the 19th century. George C. Nonte begins his article on the Crusader revolver by reviewing the various double-action revolver designs extant in 1976, providing a useful perspective on the High Standard Crusader. The Colt double-action lock-work design of 1889, which was based on the Schmidt-Galand lock of 1878, received incremental improvements which resulted in the 1905 Colt Police Positive design with a safety mechanism that prevented the hammer from striking a cartridge unless the trigger was held all the way to the rear. This fundamental design dating to 1878 was still in use by Colt’s when Nonte penned his article in 1976.

Smith & Wesson came out with their first Hand Ejector model in 1896, which was improved in 1905 by the addition of a rebound slide with a shoulder on top, and a hammer with a small shoulder on the bottom. The two shoulders prevent the hammer from resting on the firing pin. In 1915 a hammer block was added. Incremental improvements have been made since, but the company is still using its fundamental 1905 design in 2018. The first new design to appear in the 20th century was the 1964 Charter Arms, by Doug McClennahan, followed by the Dan Wesson and the Ruger double-action revolvers, but as Nonte says, “...they still didn’t exhibit any radical departure from the traditional sixgun design.” He notes that Colt’s came out with the Mk. III in 1969, but it “...offered nothing outstanding, aside from a transfer-bar internal safety. It was really a compromise of several existing designs.” He concludes: “Not really a lot to show for over 75 years...,” and “...we’ve said in print several times that a genuinely new revolver design was long overdue.” There have been few revolver innovations since Nonte’s article—even the Kimber K6S revolver’s lockwork is a copy of the Smith & Wesson, though it does have a somewhat innovative cylinder design. When Nonte was writing in 1976 the High Standard patents were not available for study. What Nonte could not tell us is that Dick Baker was careful to reference 19th century patents for a segmented gear double-action mechanism and an eccentric pivot for hammers, so he too was essentially improving on existing designs.

Externally, the only difference between the Crusader and any other revolver is the shape and function of the cylinder release. My first thought was that it should push down to release the cylinder, but instead it pushes up. I still haven’t become accustomed to this. The design of the ejector rod housing is intended to allow the shooter to grasp the end of the ejector rod and pull it forward to release the cylinder, but I find this quite difficult to do. Maybe my fingers are too fat. As related above, in the patents section, Ralph Kennedy’s intention was that the cylinder release lever would also serve as a safety lever. The functionality was as follows: the round button end of the release lever that protruded on the right side of the gun (in front of the hammer) was pressed in, and on the left side the lever was pressed down, locking the entire mechanism of the gun. A slight lift of the cylinder release lever was all that was required to unlock the safety. The reviewers of the early prototypes were unanimous that they felt the safety was unnecessary, and ultimately High Standard decided to offer it as an option only. It does not appear on the 50th anniversary commemoratives. The cylinder chambers are not counter-bored. The trigger is wide and smooth, and the hammer is wide and deeply serrated. The cylinder hand is to the left of the spindle and turns the cylinder clockwise. The Crusader is heavy, at just over 44 ounces (1253 grams). The grip is large and fills the hand nicely. People with small hands might find it a bit large, but it is proportional to the size of the gun. The wooden grip is unadorned with checkering or medallions. The double-action breaks consistently at 11 pounds and is very smooth. The single-action breaks at 4 pounds. Early reviews were careful to note that the ejector rod is full length and therefor ejects cartridge cases completely, but I did not find that to be the case. Forty-five Colt cases would hang in the cylinder, the ejector lacking about a millimeter of length necessary to eject them. The longer cases of .44 magnum ammunition would not fare even that well.

The double-action mechanism is illustrated above. The actuator attached to the rear of the trigger levers the cylinder bolt down, then releases it and locks the bolt in place. The trigger moves the hand (visible behind the cylinder locking bolt) to rotate the cylinder, and the gear segment fitted to the trigger meshes with another gear segment attached to the eccentric between the two lower arms of the hammer—the eccentric pulls the hammer downward and likewise forces the lever at the bottom of the mechanism to pull the hammer backward, and release it when the trigger is all the way to the rear. When I counted the moving parts I came up with five more than a large frame Smith & Wesson, but I’m not entirely certain I counted correctly. The single-action mechanism is virtually identical to those on traditional revolvers--a sear on the rear of the trigger that catches a toe on the hammer. The high-polish finish is a deep blue-black, of a quality that would have compared well with High-Standard’s high-end competitors. The mechanical unlocking of the cylinder bolt leaves no mark on the cylinder. I have dry-fired my gun several times and shot about 15 rounds through it and the cylinder remains unmarked. Externally, the gun is beautiful, but I can see some minor mill marks inside the frame where the cylinder rides. The portion of the frame behind the cylinder is rather roughly finished, as is the inside of the side plate. The Crusader made about a 3-inch group at ten yards, shooting from a rest. I might possibly have fired a better group in an extended session, or if I had tried various brands of ammunition to find the optimal load for the gun, but I didn’t want to shoot this rare commemorative any more than necessary. No spare parts were ever made. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright 2018 by Ed Buffaloe. All rights reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||