|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Charola y Anitúa Pistol

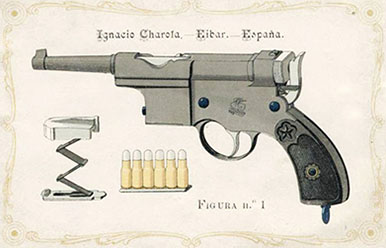

Production of the 7mm Ignacio Charola pistol appears to have begun in 1903, and is said to have ended in 1905.

The 7mm Charola was issued with a manual, but only the cover and a single page have ever been published. Collectors would very much like to see an original schematic diagram and parts list, if such were available. The cover shows a rather large factory for a company with only six employees, though it likely remained from the days when the company employed up to 39 workers. The cover proclaims “export to all countries.”

In general the 7mm Charola resembles the 5mm Type III, though none are found with the bolt locking lever of the Type IV or with Belgian proofs. The 7mm frame is slightly enlarged in all dimensions and the magazine well is made deeper to accommodate the larger cartridges. The enlarged magazine well meets the trigger guard a bit lower, so the profile of the trigger guard is somewhat altered. 7mm models all have the firing pin retained with a bayonet lug rather than a screw, which allowed the serial number to be moved to the top of the bolt crosspiece. The sides of the bolt crosspiece feature the same “inverse knurling” as the late 5mm pistols. Many 7mm guns feature a small rear sight like the late 5mm but others have a raised triangle of steel at the rear of the frame ring, with a V-notch in the center. The front sight slants down toward the front and features an integral barrel ring.

Calvó gives the barrel length for the 7mm Charola as 78mm (about 3.15 inches), though Conti gives 85mm. Like the third variant of the 5mm Charola, the top of the 7mm barrel is stamped in all capital sans-serif characters: BEST SHOOTING PISTOL The top of the chamber is marked “PATENT”. The winged bullet logo appears on the left side of the frame, but without the old company initials, and the banner reads “TRADE MARK” in English. On very late production pistols, the logo is reduced in size, has no banner, and the words TRADE MARK are found inside the bullet. The checked hard rubber grip stocks retain the star at the top but are otherwise unmarked. 5mm and 7mm grip stocks are not interchangable. Many 7mm Charola pistols are found with mother of pearl stocks, some of which are clearly taken from revolvers.

There are two variations of the 7mm—one with an internal fixed six-shot magazine, and one with a detachable eight-shot conventional magazine. The internal six-shot version is easily converted to the eight-shot detachable version. Stewart believes that all of the 7mm pistols were made in one batch, with individual frames converted to the detachable magazine as necessary. He says: “The floorplate latch channel and front dovetail are filled by a pinned-in block, and the alteration concealed by minor decorative engraving on the front of the magazine well. In order to retain the magazine a transverse hole is bored in the frame to accept a cross-push release. At some later time pistols, or numbered frames on hand, were altered to the detachable magazine system.” Charola pistols with detachable magazine observed by the author do not have a latch channel cut for the baseplate release button, but usually have the decorative engraving mentioned by Stewart. A retaining nut on the right side serves as the button release for the magazine. Detachable magazine versions are found scattered throughout the serial number range, but are much less common than the integral magazine version.

The magazine is formed from sheet metal, low cut at front and rear to accommodate the bolt, and with tabs on either side that fold under at the bottom to retain the sheet metal baseplate. There are no holes for viewing cartridges. Most magazines are unblued. The magazine follower is made of aluminum—certainly an early use of aluminum in an automatic pistol, but the production 1900 early model Luger pistol also used aluminum for the same component. Stewart relates that: “The magazine lips, which come up high on the bolt sides, are completely bent over and, by means of tall ears on the sides of the cast aluminum follower, hold the follower below the path of the bolt.” He also reports that some magazines are numbered to the gun, though the author has not observed any.

The 7mm pistols have an unusual feature which is not discussed in any of the literature. There is a lug on the bottom of the bolt and a notched lever in the action group, which do not appear on any of the 5mm pistols—with hammer cocked, when the bolt and receiver are pulled back about 7 millimeters or so, the notched lever catches the bolt lug and holds bolt and receiver slightly to the rear.

The most likely explanation for this unusual feature is that it serves to hold the breech open just enough to see whether or not there is a cartridge in the chamber, and so it provides an easy means of determining, at a glance, the condition of the pistol. In 1903, knowledge of automatic pistols was not widespread and, without this mechanism, when the breech was closed there was no way of knowing whether or not a Charola pistol was loaded. All sources give 1903 as the date for the origin of the 7mm Charola cartridge. White & Munhall state that the earliest reference to the cartridge is found in specifications from the Socièté Francaise des Munitions dated June 1903. The 7mm has the same case length as the 5mm, but the case diameter is .059 inches greater, and the bullet diameter is .081 inches greater. The 7mm Charola cartridge is sometimes referred to as the 7mm Teuf Teuf, presumably because some specimens of the 7mm Charola are found with “TEUF-TEUF” engraved on the upper flat of the receiver. “Teuf-teuf” translates from French as “choo-choo,” “chug-chug” or “putt-putt,” and appears to have been first used in relation to steam locomotives, though the Oxford English Dictionary supplement says “teuf-teuf” is “[a]n imitation of the repeated sound of gases escaping from the exhaust of a petrol engine,” and was first found in English language usage in the Daily Chronicle newspaper of 1902, after which it was in regular usage for a decade or two (by the likes of George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, and others). Perhaps its usage in regard to the Charola was a marketing ploy for sales in Francophone countries, though no one seems to know for certain. While the last two variations of the 5mm pistol share some similarities with the 7mm in both markings and construction, it is not known for certain if they were made concurrently. It seems likely that the 5mm pistols were made in the earlier period between 1900 and 1903, while the 7mm guns were made later, between 1903 and 1905. The 7mm pistols required different frames and barrels. Nonetheless, assembly of 5mm pistols from existing parts might have continued during 7mm production.

Stewart says: “The 7mm Charola pistols as a group show much less variation and were obviously made over a relatively short period of time. Both variations are numbered in the same series, beginning at 10,000.” Calvó declares: ... it is likely that the manufacturers, also for commercial purposes, falsified the numbering by exaggerating it.” The highest serial number mentioned by Stewart is 11,935, and none have yet been observed in the 12,000 range, so it is believed that about 2000 total 7mm pistols were made.

Ignacio Charola submitted the 5mm pistol to the Spanish Army Experimental Commission, which was tasked in 1896 with selecting an automatic pistol for use by the Spanish military. The pistol was rejected for military use in the earliest years of the twentieth century due to its small caliber and low power. As a result, Charola decided to develop the 7mm cartridge. Probably writing in 1902, and published in 1903, Juan Génova relates: “Due to its very small caliber, this pistol does not go beyond the category of a parlor weapon, since the low lethal power of the projectile does not allow it to be considered a war weapon or even for personal defense. To correct this deficiency, Mr. Charola is trying, according to our information, to build another model of greater caliber.” Cartridges, in both calibers, were sold in boxes of 30, containing five stripper clips with six cartridges each. Early 5mm cartridges were likely produced by Keller & Company of Hirtenberg, Austria. Other known headstamps include C.R.B. Liege (Cartoucherie Russo-Belge), D.W.M. (Deutsche Waffen und Munitionsfabriken), G.R. (George Roth & Co.), and S.F.M. (Société Française des Munitions). The 1903 Clement pistol was also chambered for the 5mm Charola cartridge, and was somewhat more successful than the Charola, so the cartridge soon became known as the 5mm Clement. The 5mm Clement cartridge was still listed in the Fiocchi catalog as late as 1961. If, as reported by White & Munhall, the 5mm cartridge launched a 28 grain bullet at 1030 feet per second, it would result in 66 foot-pounds of energy at the muzzle, which is roughly equivalent to a 6.35mm Browning (.25 ACP) cartridge (averaging 60 to 70 foot-pounds). The 6.35mm Browning cartridge, of course, did not exist when the 5mm Charola cartridge was designed. Génova references a 3.3 gram (51 grain) bullet at 300 meters per second (984 feet per second), which would result in 110 foot-pounds of energy. He also reports an optimistic maximum range of 800 meters, penetration in pine wood of 85mm, and in beech wood of 65mm. Juan Calvó comments that, “...these last data were undoubtedly offered by the manufacturer, erring on the side of exaggeration...”

The 7mm Charola cartridge, like the 5mm, was manufactured by Keller & Company of Austria, the Société Francaise des Munitions, and Deutsche Waffen und Munitionsfabriken; and can also be found in boxes labeled “7mm Teuf Teuf.” The 7mm cartridge of 1903 is reported by White & Munhall to drive a 62 grain bullet at 722 feet per second, providing about 71 foot-pounds of energy, hardly more powerful than the 5mm. No other ballistic data on the 7mm cartridge is available. The 7.65mm Browning (.32 ACP) cartridge typically generates between 117 and 148 foot-pounds of energy, making it far more efficacious than the 7mm Charola—even so, it is sometimes considered inadequate for self defense. According to the Manual of Pistol and Revolver Cartridges, production of the 7mm cartridge ended around 1912.

James B. Stewart opines: “The pistol’s size, appearance, and scaled-down ammunition would seem to indicate that it was essentially conceived as a toy for the wealthy, rather than as a serious weapon of offense or defense.” Ian V. Hogg says: “...it is assumed that the guns were little more than an experiment.” In any case, the metallurgy of the Charola is not likely to have withstood a more powerful cartridge. Stewart relates: “...they were made of quite soft and often inferior materials. Basic components such as the action subframe and lockwork, and possibly also the frame and receiver, were machined from sand castings. Many pistols are found with broken or improperly tempered springs, particularly the locking lever spring. Others show much battering of the recoil spring retaining block in the receiver, indicating that even with the locked action the recoil spring is not up to coping with the relatively small forces involved.”

Jesús Madriñán says the Charola was first used in Russia during the Russo-Japanese war of 1904 to 1905. Fox indicates that the Charola was used in Mexico and Russia during their respective revolutions in 1910 and 1917. He notes: “The personal handgun of General J. Agustin Castro [SN 939], one of the [Mexican] revolutionary leaders, was a Charola y Anitua.” Additionally, a 7mm Charola (serial number 10238) is known to be inscribed on the side of the magazine well, “Presented to F. C. Laurie by General R. Balboa of the Villa army, Mexico.”

Low power or no, the Charola might have been more widely adopted, were it not for its exotic and difficult to source ammunition. The 5mm Charola pistol is sometimes found either re-barreled or with barrel re-bored and re-chambered for the 6.35mm Browning (.25 ACP) or even the .22 Long Rifle, while the 7mm has at times been converted to shoot the .32 Smith & Wesson cartridge or the .32 ACP. A spacer is installed in the rear wall of the magazine well, and a smaller magazine is fabricated. Stewart believes that all such conversions were done in Mexico.

Comparing the Charola lockwork to that of the Mauser C96, Conti says: “...it seems that the Spanish weapon dates back to half a century earlier, when in fact it was born a few years after the Mauser.” But, considering the state of technology in Spain in the period 1898 to 1905, Charola pistols are remarkably well made. Conti comments: “...the charm of this sort of miniature remains intact, anything but "crude" as many American authors have defined it, and certainly better finished than the American authors themselves have always told us.” One can only wonder what “American authors” Conti is referring to—he obviously has not read Stewart, who says: “Charola pistols are, on the whole, quite graceful in appearance and nicely machined and finished.” Due to the early date of these pistols, and the fact that both calibers of Charola ammunition are now obsolete, the ATF classifies them as antiques. There are no restrictions on sales or ownership of the Charola pistol in the United States.

The Charola breaks down into four main groups:

Conti comments: “I do not recommend anyone who is not at all confident about their patience and experience to try to disassemble the Charola Anitua.” However, the author has found that basic disassembly is relatively routine, with the exception of removal of the bolt from the receiver.

Removal of the grip frame "action group" is a simple matter of removing the screws from the right side and pushing out the keyed posts to the left. The screw heads are not tall, so the slots are shallow and easily damaged—a correctly sized screwdriver and careful attention are essential. The posts serve as pivots for the hammer and locking lever. Cock the hammer to take tension off the rear post. The grip frame and attached lockwork simply slide down and back. They must be removed first, before barrel, receiver, and bolt can be disassembled and removed from the frame.

With the grip-frame removed, grasp the barrel, pull forward just enough to allow the front lug on the bottom of the receiver to clear the front of the frame, and lift slightly. This draws the receiver and barrel forward enough to expose the transverse key which locks the bolt in place. Removal of the bolt begins with removal of the firing pin. On 5mm models, remove the screw from the top of the bolt crosspiece, and withdraw the firing pin. On 7mm models, lock the bolt open slightly and use a screwdriver to press in on the firing pin—turn counterclockwise to release. Removal of the bolt from the receiver is not for the faint of heart and should not be attempted unless necessary, because the recoil spring tends to want to come out the hole in the right side, along with the transverse key, instead of out the back of the bolt. The best method is to find or make a tool that is the exact size of the cut in the left side of the receiver, and punch the key out quickly. Lift up slightly on the barrel/receiver and slide it back through the frame ring enough to allow removal of the key. Removal of the transverse key in the bolt must be done against the considerable pressure of the compressed recoil spring, which butts up against the key. It is necessary to make a small wooden block to hold the bolt open by about 10 mm, and place it between the barrel and the bolt (or else hold the bolt with your third hand). This will expose the key to be pushed out from left to right.

Reinstallation of the recoil spring is accomplished with a punch of the correct diameter to fit through the hole in the bolt. Once the recoil spring is secured with the transverse key, the rest is easy. The screw posts (Conti calls them “counterscrews”) are keyed and will only fit when installed exactly in the correct position. Early Charola pistols have registration marks on the posts and

frame, which were eliminated on later guns, so you have to pay careful attention to orientation when inserting the posts. Part I: Historical Background and the 5mm Charola

Since the author only has direct access to two 7 mm pistols, this article is based on information from previously

published materials, which requires assessment. The earliest mention of the Charola is in Juan Génova’s 1903 book Armas Automáticas. It only covers the 5mm pistol, but he provides perhaps the best and most detailed

information about the functioning of the pistol, plus early data on the 5mm cartridge. Juan Calvó clearly had access to this book, but does not reference it. H. B. Pollard merely mentions the Charola in his 1920 book,

whereas R. K. Wilson does not (in his Textbook of Automatic Pistols). W. H. B. Smith (in his book Pistols & Revolvers) mentions the Charola, only to incorrectly state that it somehow derived from the Bergmann. Ian Hogg

lists the gun under Garate y Anitua in both of his 1978 books, but corrects this in his 2004 Pistols of the World—his technical information is good, but the historical information is not always accurate. The first modern

article with detailed information about the mechanism, and a typology, was written by James B. Stewart in 1968, and it remains the best source available. Steven Fox’s 1985 article contains some new information about

variations and the number of each variant produced. Juan Calvó is the first to provide accurate historical information and a partial copy of the patent drawing. The full patent drawing and the text of the patent have never

been published. Paolo Conti’s 1992 article, while not entirely accurate historically, is among the best for technical information. Conti probably had access to Fox’s article. The most recent (2016) article in Armas Internacional provides nothing new but has some nice photographs.

Acknowledgments Special thanks to Bill Chase and Steven B. Fox for photographs, information, and discussion of the Charola pistol; and to Michael Carrick for providing the author with copies of two of Calvó’s books. Thanks also to Al Gerth for helping verify features, and to Robert Adair for information, discussion, and sharing the portion of his unpublished book which relates to the Charola pistol. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright 2025 by Ed Buffaloe. All rights reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||