|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Ed Buffaloe Interviews

Robb Kendrick: Probably...27 years. E.B.: That’s a pretty long time. How did you get started? R.K.: We moved from Nebraska back to Texas (my Dad got transferred up there for a few years). Up in Nebraska I was on the wrestling team and the swim team and track team. When I got back to Texas we moved to a small town and they didn’t have any of those athletic programs--exept track, and it was a pretty pitiful track team. So I just picked up photography. My uncle took a lot of photographs in Vietnam and he gave me a box of photographs when I was 7. I was always intrigued with them. When I was 15 I decided to pursue another outlet, since swimming and wrestling weren’t a big part of where I went to school in Texas. E.B.: Did your uncle give you any cameras? R.K.: No, he didn’t. At one time he promised he would give me a camera if I got interested. I had started shooting pictures actually when I was 7, but not seriously until I was 15. But at 7 he showed me these pictures and said if I learned how to do it he would give me a camera. So I started shooting pictures with an Instamatic that I still have today. I shot pictures of trucks at truck stops, thinking that I wanted to be a truck driver and travel the U.S.A., get paid to be a truck driver. So that’s kind of where it all started. I simply started showing him some pictures. He had some emotional problems, I think, due to his time in Vietnam. He just kind of disconnected from the family totally, so I never got to take him up on his offer of a camera. E.B.: Did you study photography? R.K.: Yes. I went to school at East Texas State, now Texas A&M at Commerce. After high school, I went there in ‘81 and stayed for about three and a half years. I had a great instructor, Jim Newberry, who was part of the program at that time. E.B.: When did you start working for National Geo?

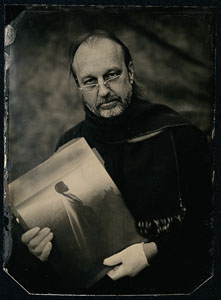

E.B.: How did you start making tintypes? How did you get interested in the process? R.K.: I’ve always loved the way tintypes look--I started collecting them when I was 18. I probably have, I don’t know, approximately 3 to 5 thousand tintypes in my collection. I’ve always had an interest, and thought... they’re very beautiful, very durable. I guess it was six years ago I read a story in the New York Times about a gentleman who gave up his life in Florida and moved to Upstate New York to pursue photography and live a totally different lifestyle. He’d been an underwater welder. His name is John Coffer, and he worked at a portrait studio, shooting school portraits. He gave that up, sold everything, bought an 8x10 camera, and moved to Upstate New York, near where the Amish communities are. I read this story, and read that he was doing tintypes, and so I found his address and wrote him and asked if I could take a workshop. I was very frustrated with my own work professionally. I didn’t get into photography to make money, even though you can make a good living at it. I got into it because I loved it, and I find that the more you do it for other people, the less control you have. When you’re doing it for jobs it’s not necessarily images you would make if you weren’t trying to make a living at it. So after having my own business for 15 years--I’m somebody that’s constantly experimenting with homemade lenses, and stuff like this, but I was just totally frustrated with my professional career, the way it was going--even though I’d had a lot of fortunate breaks and great experiences I just decided to take my midlife crisis and go see if I could learn tintypes. I thought, it’s the closest thing to art in photography to me, because there’s only one. You can scan it, you can make prints from it, but it’s probably one of the few things, except maybe for Daguerreotypes, that are “one of’s” in photography.

E.B.: Can you describe the technical process of making a tintype? R.K.: Yes. Basically, you start out with Japanned plates, which are blackened plates. There are a couple of individuals who do it the old way--it’s not on aluminum, it’s on tin plates--and you can occasionally find them on eBay, or you can make them yourself. Once you have the blackened plates, you can have as many as you want and you can travel around with this blank slate to start with. E.B.: Are they really tin, or are they pieces of iron? R.K.: It’s bright tin. E.B.: I read somewhere they were called ferrotypes.

E.B.: But the substrate is not particularly critical? It just needs to be painted black, and something that’s not too flexible? R.K.: The tintypes are pretty flexible, I’d say. But if you want to do it in the 19th century way, you’d use the bright tin with Japanning as opposed to “painted black.” E.B.: Is “Japan” some kind of varnish? R.K.: Japan solution is asphaltum, which is I think used in the printing industry--I’m not quite sure--and then you mix it with ether, I believe (I’d have to get my book out), and Everclear, and you have to bring it to a low boil to get it to the right consistency. Then you paint that two to three times on the surface you’re going to shoot on, and once on the back side, and then you cook it in an oven (or, John Copper does it over a fire). I use a plate cooking box that I had made. I have gas burners underneath. I bring it to a consistent temperature. You bake the Japanning solution on. E.B.: So it forms a real hard, shiny surface? R.K.: Exactly. And that becomes your black background. The chemicals will last approximately four weeks from the time you mix them to the time you need to use them. Some of them will last longer. Like the lavendar varnish, but the developer has about a month shelf life, the collodion probably has a four month shelf life.

E.B.: So it’s basically a wet plate process. You only dry it enough to firm it. Then you sensitize it, put it in the camera, take the picture, and it’s got to be developed before it dries completely. So what is it developed in? R.K.: I use an 1850’s formula that’s basically iron sulfate, Everclear and distilled water, and it’s got a few other items in it--I’d have to get my formulary book--ammonium bromide, ammonium iodide and a few other things like that. And you always add a little bit of old developer to the new developer, because there’s silver in there and it needs some of that.

R.K.: I go through three water baths for 20 to 25 seconds apiece. That just stops the development process and washes the iron sulfate out of the collodion emulsion. The last step in the development process is to put it in potassium cyanide. You can use sodium thiosulfate, but the difference is, if you want that creamy color in the highlights and midtones, you have to use potassium cyanide. Otherwise, those areas that are creamy in a typical tintype would just be grey or white. So, I put it in the potassium cyanide for anywhere from 20 to 35 seconds. That kind of clears the image and gets all the iron sulfate out and turns it from a negative looking image to a positive. E.B.: Are there any particular precautions you have to take using potassium cyanide? It’s pretty poisonous stuff. R.K.: Right. When mixing up the initial batch I use a respirator. After that you have to be careful that it is not stored in a glass bottle--if it broke and cut you it would be detrimental to get it in your bloodstream. You have to be very careful when you’re working--if you have cuts from handling the tin or whatever--to wear gloves. I typically don’t wear gloves unless I have cuts. E.B.: What about collodion? Is it particularly dangerous in any way?

E.B.: The use of the lavendar oil as varnish, is that how you got interested in growing your own lavendar? R.K.: No, it just happened. I started growing the lavendar a year before I started on the tintypes. E.B.: Are you aware that in some, particularly third world, countries people were making tintypes into the 1950’s? R.K.: Oh yeah. I knew that. E.B.: Have you collected any like that? R.K.: I haven’t found any of those, actually. I typically find mostly Western European and American tintypes. E.B.: I’d really like to see some of these 20th century tintypes. Apparently it was a really cheap way to make an image.

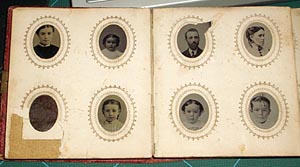

E.B.: That reminds me that it really was a kind of people’s photographic process, from the earliest days. For instance, Julia Margaret Cameron started making photographs using techniques that had been established by Fox Talbot, but she was wealthy, she could afford to buy all the chemistry, and she had the time to mess with it. The average person couldn’t do that. I think in the earliest days of photography it was mostly something that fairly well-to-do people did. Whereas, the ambrotype process and later the tintype process enabled the average person to have their own copies of photographs--their own pictures. R.K.: Exactly. I think the tintype was probably one of the innovations from America--as far as I understand it, it was an American innovation. It was affordable and approachable by many people. That’s why you see all these little albums--these were probably middle class and lower class citizens who could afford to have pictures made. You don’t see a lot of tintypes of African Americans, but the ones that you do are typically people who had a little money, but probably not enough to have a glass plate negative made.

R.K.: I think...whatever people are interested in doing, I think it’s great. A couple of people I know of have tried to say that they are tintypes, and I think that is a little misleading. Really, what a lot of people do is paint--blacken--aluminum, and they put Liquid Light on, and you can make 500 pieces of light sensitive tin and store it like paper. And then they print their images--they’ll shoot with a contemporary camera, and they’ll come back in the darkroom and make prints on tin. For me personally that’s not as special, because what’s the difference between making 50 prints on paper or 50 prints on tin? I mean, I like the way they look, but to me the all-hand -made nature of the original tintype process makes it definitely much more special. Each one is a real hair -pulling experience. You go through a lot of trauma to do it, because every step of the way it’s susceptible to scratching or whatever, so the final image...there’s only one of.

I like some of the images that are made using the contemporary tintype, as it’s called, but they definitely don’t hold the same value for me as the traditional, historic tintypes. There’s one person I know who shoots with a 2¼ Hasselblad and prints on tin, using this Liquid Light. If you use a modern lens to get a totally sharp image, and put it on a plate that has very few defects (because it’s not really handmade, the plates are anodyzed aluminum) it seems like extra effort to go through without any of the handmade qualities of the 19th century images. If the person were shooting on film using a 19th century lens and at least gave it the kind of quality that the old uncoated lenses have, it might look a little more real. But, if that’s not their aim... E.B.: So I take it then that all the lenses you shoot tintypes with are old lenses--original?

E.B.: Are any of them soft focus lenses. R.K. Yeah. I’ve got, I think, about 50 or 60 of these lenses, and they run the gamut from the very first true wide angle lens from 1852 to soft focus portrait lenses. I say soft focus, but really the center is extremely sharp. They were trying to make fast lenses to have shorter exposure times, so the outside edges are less sharp. I do use a Wisner 8x10 for my main camera, but the lenses are period. Everything else I kind of had to scrape to pull it all together to shoot. Just making the images is difficult, because you’re using all these chemicals that you are mixing up from scratch, because they don’t come in a kit; and then Japanning the plates is a whole new art. There’s a lot of struggles along the way just to get to the point where you can consistently make good plates. It took me probably a year and a half to get to a point where I felt like I was consistent enough and getting good enough results that I could show people.what I was doing and get them to consider letting me do projects that I would care about. I had somebody say “you want to go shoot some chefs in tintype?”...Fortune magazine. E.B.: Not interested? R.K.: No, I have no interest in chefs. I don’t think it’s the right subject for what I want to do.

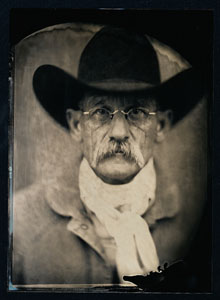

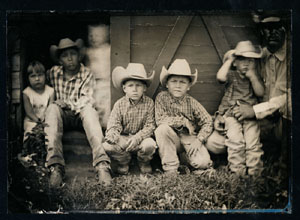

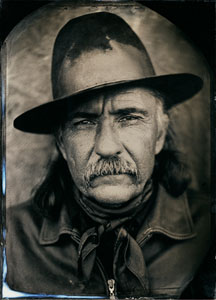

R.K.: Nevada. E.B.: Nevada? Did you find some subjects there that interested you? R.K.: Yeah, that story came out October of last year. It was great. Elko is a perfect place for tintypes, because it’s where everything we think of as

the Old West comes together. The state still has legalized prostitution, legalized gambling, ranching’s big, gold mining’s huge, and so you have all

the cultural icons of the Old West come together and still very much alive there. It was for one of those stories they call Zip Codes, which are

usually three to five pages, and Elko got eight pages. So they really loved it. They did a little Quicktime movie on the website. It shows the whole

process--me doing the whole process from start to finish, in this trailer.

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|