|

Archival Processing of Prints

by Ed Buffaloe

Silver halides are the most sensitive materials available for use in photographic emulsions, but unfortunately metallic silver oxidizes very readily, so that silver images formed in our photographic negatives and prints require

protection or stabilization in some way. Archival processing involves fixing film and paper adequately to remove unexposed silver halides, washing appropriately to remove excess fixer, and preferably treatment with some

sort of toning or sequestering solution to prevent the emulsion silver from oxidising in the presence of various environmental pollutants. In this article, I am primarily concerned with photographic prints rather than

negatives.

Fixing:

Adequate fixing is necessary to remove unexposed silver halides, which, if left in place, would react with light and degrade the image. Most practitioners today use Ilford’s processing method for prints, which specifies rapid fix (with ammonium thiosulfate instead of sodium thiosulfate) at “film” strength, i.e., diluted 1:3 or 1:4 instead of the old “paper” dilution of 1:7, for about one minute (compared to the 5 to 10 minutes required in a sodium thiosulfate fix). The concentrated ammonium thiosulfate provides adequate removal of unexposed silver halides while reduced time in the solution prevents fix from penetrating into the paper base where it is very difficult to remove. Photographers would do well to remember that over-fixing of prints is equally detrimental  to archival quality, in the long term, as under-fixing. My personal method for prints is to utilize two trays of rapid fix, agitating the print

in each tray for 30 to 45 seconds. When the second tray of fix has reached half its recommended capacity, it moves to the first tray and I prepare a second tray of fresh fixer. The

two-tray method increases the useful life of the fix by reducing contamination in the second fix, assuring adequate fixation. Kodak’s “Residual Silver Test Solution ST-1” may be used to

determine if paper or film is properly fixed. I should note that the traditional method of fixing prints in a sodium thiosulfate solution for 5 to 10 minutes is perfectly acceptable, so long as fixing

and washing times are adequate. to archival quality, in the long term, as under-fixing. My personal method for prints is to utilize two trays of rapid fix, agitating the print

in each tray for 30 to 45 seconds. When the second tray of fix has reached half its recommended capacity, it moves to the first tray and I prepare a second tray of fresh fixer. The

two-tray method increases the useful life of the fix by reducing contamination in the second fix, assuring adequate fixation. Kodak’s “Residual Silver Test Solution ST-1” may be used to

determine if paper or film is properly fixed. I should note that the traditional method of fixing prints in a sodium thiosulfate solution for 5 to 10 minutes is perfectly acceptable, so long as fixing

and washing times are adequate.

Washing: Adequate washing is necessary to remove residual thiosulfates (fix) in the print, which could otherwise

cause the print to deteriorate over time. However, recent studies at the Rochester Institute of Technology’s Image

Permanence Institute (RIT IPI) indicate there may be as much danger in over-washing as in under-washing. Doug

Nishimura of RIT states, “...it has been proven at Kodak, Fuji and here at IPI that a small amount of hypo will make

photographs MORE stable against air pollutants and that overwashing decreases the stability.” He is referring to

untoned silver images. He further states that, since it is difficult to wash until the optimum amount of residual

thiosulfate remains for perfect preservation of the silver image, IPI recommends an after-treatment to convert image

silver to something more stable. Over-washing can also leech out the optical brighteners that are added to most modern papers.

With the use of a wash aid such as Kodak Hypo Clearing Agent, Orbit Bath, or Perma Wash, the time required for

washing prints can be reduced to a half-hour or less, assuming that Ilford’s method of rapid fixing has been followed.

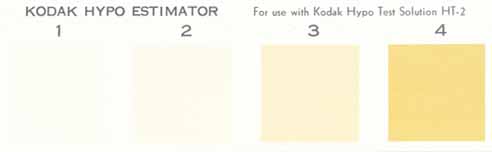

(I personally do not use Perma Wash for prints, though I do use it for film.) Kodak’s “Hypo Test Solution HT-2”

may be used to determine (approximately) if paper or film has been properly washed. To test for uniform washing of

paper, develop and fix a blank, unexposed piece of paper. Then test various portions of the paper with HT-2 test

solution. Because of the variability of water quality and print washers, the only way to ascertain if washing is

adequate is to test (see test description below). I strongly recommend turning your prints 180 degrees halfway through the wash cycle to increase uniformity of washing.

Toning:

Perhaps the most shocking discovery of the past couple of decades has been that the noble metals in many popular toners do not always provide adequate protection for silver images. Silver is only protected from

oxidation to the extent that it is completely replaced or plated over by a more stable element (gold, platinum, or

palladium) or forms a more stable compound (such as silver sulfide or silver selenide). Experiments at RIT’s IPI,

which involved toning microfilm in Kodak Gold Protective Solution (GP-2), indicate that this solution is equally

effective for microfilm when the gold chloride is omitted.. This came as a surprise, since researchers had long

assumed that gold was the active protective agent. IPI test results indicate the thiourea (thiocarbamide) in the

formula is the effective ingredient, converting image silver to stable silver sulfide. While sulfides are the chief

pollutants which cause image degradation, the complexes they form with ionic silver are quite stable; therefore, IPI

has determined that the best protection for silver film images is intentional sulfiding. However, Liam Lawless tested

Kodak’s Gold Protective Solutions with a contemporary enlarging paper, and his results indicate that the gold is a necessary ingredient for fiber papers. (See Testing Gold Protective Solution.) Liam’s results also indicate that GP-2

is more effective than GP-1, at least in the chromic acid bleach test that he used.

Platinum is rarely used as a toner for silver gelatin papers, due to its expense. However, it does see some use for

toning kallitypes, where the total quantity of silver to be toned is somewhat less than in a gelatin silver print. Luis

Nadeau notes that experiments performed by Ilford in the 1970’s with a very old platinum toner formula caused image destabilization, but he was did not provide details as to the exact toner formula or the exact problems

encountered. Platinum is considered to be the most stable noble metal other than gold, and it definitely merits further testing. Platinum gives a very neutral black image when used to tone silver prints.

Selenium remains the most popular toner among fine art photographers. It converts silver to silver

selenide, and causes a color shift with most papers, ranging from purple with bromide papers to reddish-brown with chloride papers, which many people find quite pleasing. Doug Nishimura

cautions that partial toning or split-toning with selenium will leave the untoned portion of the print unprotected, as the selenium preferentially tones finer grains of silver in high-density areas of the

print first. Untoned portions of the image may be subject to future deterioration. This flies in the face of longstanding advice from Kodak which, as repeated by Ansel Adams and many others,

said that selenium provides protection even in very high dilutions which do not cause color changes. Apparently at one time Kodak Selenium Toner may have contained “small amounts of highly active sulfiding

agents” which provided protection that selenium alone cannot provide unless toning is carried to completion. At

some point in the 1980’s manufacturing changes eliminated these agents. Doug Nishimura indicates (in a letter to

Jennifer Scott) that complete protection with Kodak Selenium Toner requires a dilution of not more than 1:9, and a

toning period of 3 to 5 minutes at 68º. Some fine art photographers find this depth of toning not to their taste. Selenium remains the most popular toner among fine art photographers. It converts silver to silver

selenide, and causes a color shift with most papers, ranging from purple with bromide papers to reddish-brown with chloride papers, which many people find quite pleasing. Doug Nishimura

cautions that partial toning or split-toning with selenium will leave the untoned portion of the print unprotected, as the selenium preferentially tones finer grains of silver in high-density areas of the

print first. Untoned portions of the image may be subject to future deterioration. This flies in the face of longstanding advice from Kodak which, as repeated by Ansel Adams and many others,

said that selenium provides protection even in very high dilutions which do not cause color changes. Apparently at one time Kodak Selenium Toner may have contained “small amounts of highly active sulfiding

agents” which provided protection that selenium alone cannot provide unless toning is carried to completion. At

some point in the 1980’s manufacturing changes eliminated these agents. Doug Nishimura indicates (in a letter to

Jennifer Scott) that complete protection with Kodak Selenium Toner requires a dilution of not more than 1:9, and a

toning period of 3 to 5 minutes at 68º. Some fine art photographers find this depth of toning not to their taste.

Kodak Polytoner, which contains both selenium and sulfide, is probably more effective than selenium toner alone for

archival purposes, but I personally have never been able to obtain precisely the tones I desire from it, and it is no longer made by Kodak..

Sulfide and polysulfide toners (brown and sepia toners) always transform print color to a brown or yellow-brown, but the resulting image is quite stable.

Other Treatments:

Agfa makes a product called Sistan, and Fuji makes a similar product called AG Guard, which is used to treat prints after washing. Thomas Wollstein has corresponded with Agfa regarding Sistan, and tells us

that Sistan contains potassium thiocyanate and a wetting agent--it works by converting oxidized silver ions in the

emulsion to a stable, insoluble salt. Robert Chapman states that Sistan “...precipitates any silver ion formed by

oxidation in the form of silver thiocyanate (AgSCN). Silver Thiocyanate is colorless and virtually light-insensitive.”

But Sistan only works as long as the thiocyanate stays in the emulsion, so Agfa recommends that Sistan be used as a final treatment, after washing and before drying--if it is washed out, archival benefits are probably lost.

According to Doug Nishimura, “before any silver deterioration can occur, silver must be oxidized into silver ion.

Even air and moisture can act as a strong enough oxidizing combination to cause damage.” He notes that “...there is

always a small amount of ionic silver in equilibrium with silver metal in a photographic image.” But, whether the ionic

silver already exists in the emulsion or is caused by pollutants, thiocyanate combines with it, thereby stabilizing it as

an inert salt which will not cause image degradation. Sistan is said to be fully compatible with toning treatments. I

should note that Dupont 6-T Gold Toner contains potassium thiocyanate, and Kodak GP-1 contains sodium thiocyanate, but I do not know if either is in sufficient quantity to be as effective as Sistan is alleged to be--also,

prolonged washing would negate any benefit derived therefrom. Robert Chapman states that, though he has inquired

several times, Agfa has not provided him with substantive documentation to prove the effectiveness of Sistan. He

allows, however, that “..it makes sense on theoretical grounds.” Other sources on the world-wide-web hint that

Sistan may not be effective over the long term, but there is no hard data to back this up either.

Long Term Stability: Doug Nishimura of RIT’s Image Permanence Institute has emphasized repeatedly that image

permanence is tied more to storage conditions than to processing. No matter how carefully processed an image is, if

it is subjected to atmospheric pollutants it will be liable to degrade. In a letter to Jennifer Scott of the State Library

of South Australia, he tells an anecdote about photographic prints on display in a gallery that suffered deterioration in

a matter of weeks in the form of orange spots, which resulted from the fumes produced by a repainting of the gallery

walls prior to the exhibit. In a web post he states: “...we find that of the thousands of photographs examined here at

IPI, we rarely find deterioration from hypo retention. Virtually all of the fading seen in photographs has been caused by [contaminants in] air and moisture.”

In the November/December 2000 issue of View Camera, Michael A Smith published a very interesting article

entitled “Advances in Archival Mounting and Storage: Ultimate Protection for Your Photographs,” which is an

interview with Bill Hollinger. In this interview Mr. Hollinger discusses the ArtCare mounting board which he invented

. ArtCare board is designed to absorb and sequester environmental pollutants, preventing them from attacking

photographs. When queried as to where such pollutants come from, he stated: “The acids are emitted by wood,

plywood, particle board, and chipboard, and the formaldehydes are emitted by carpets, draperies, upholstery, and

certain plastics. In addition, sunlight entering a building causes the buildup of ozone, peroxides, nitric acid, and other

nitrogen-containing molecules...” Dramatic examples of accelerated aging tests are shown in the article. Judging from

the examples, ArtCare board appears to be superior to 100% rag board for long-term preservation. Test results

also indicate that dry-mounted prints, no matter what board they are mounted on, fare better than prints that are

hinged or corner-mounted. The dry mount tissue serves as a barrier to pollutants that have been absorbed by the mount board.

|

|